City state Holland – why it matters for pig producers

My country is evolving into a city state. Instead of cities in an agricultural landscape, the Netherlands eventually is going to consist of cities with natural parks and scattered patches of countryside. The current farmers’ protests and nitrogen debate are part of a bigger picture.

A cauldron in a fireplace, perhaps that is an appropriate way to think of what the debate on animal agriculture is like in the Netherlands.

For years – especially after the Second World War – the heat was on underneath that cauldron. The Netherlands needed a decent food supply, to avoid any more winters of starvation. A blossoming agriculture emerged in the post-war years. Vegetables and fruits grew in state-of-the-art greenhouses, and we shipped colourful flowers around the globe. Our milk and cheeses got world fame and our pig industry served as an example for many. Today, the Netherlands is the number #2 agricultural exporter in the world.

I am afraid that is all going to change. For swine countries all over the world, it is important to take notice of what is happening in the Netherlands right now.

Growing human and pig populations

Growing human and pig populations

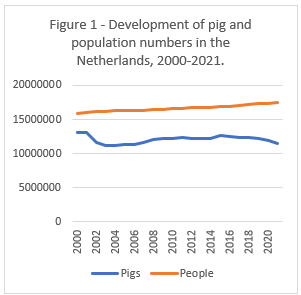

Let’s take a quick look at where all thriving policies have led to in the last 20 years. Figure 1 shows that whilst the human population has continued to grow to well over 17 million, pig numbers have been veering around 12 million. Pig numbers peaked in 1997 (15.2 million pigs), when Classical Swine Fever (CSF) marked the end of years of growth. The virus and subsequent policy changes led to a stabilisation of pig numbers around 12 million for years until recently.

Critical voices

Over the years, our cauldron filled up with a rich variety of flavours and spices. Apart from farmers and agricultural organisations, also parliamentarians, media celebrities, activists, welfarists and environmentalists joined in, giving new flavours to the brew.

A consensus around “food security” gradually gave way to a multitude of critical voices, mostly for environmentalist or animal welfare reasons. Some called for more organic production, or a reduction of meat consumption, others stated that eating meat is no longer morally acceptable. In the Netherlands, that tendency found its way into parliament with the emergence of the world’s first “Animal Party” (PvdD), a political party aimed at changing conventional animal agriculture, if not reducing it. It has been in the Dutch parliament since 2006, now occupying 6 out of 150 seats, representing a similar slice of society wanting the same.

As a relatively recent ingredient to our brew, “nitrogen emissions” were added. Perhaps it sounds innocent, but it has turned a green soup into something explosive. Here is why.

Natura 2000 network and biodiversity

The problems are related to the so-called “Natura 2000” network, a European Union scheme to protect its forests, moors and waters. Each country identified and submitted valuable areas of nature under this plan, and each country committed to protecting those, including upholding biodiversity levels. In total, the Netherlands has 162 of these areas. Some larger, the majority relatively small – do not think all areas have the size of Yellowstone or Kruger Park.

Now many factors can influence biodiversity. That includes nitrogen, in particular when that comes in the forms of nitrogen oxide (NOx) and ammonia (NH3). Those chemical compounds encourage the growth of certain plants – think of e.g. nettles and certain kinds of grasses – which can grow at the expense of others. When those can grow, the change in vegetation may lead to a change in insect, bird and mammal populations. Biodiversity could be at stake.

Overruling of nitrogen legislation

For years, it was thought the situation was under control by legislation – until 2019. In May of that year, the Netherlands’ highest court ruled that existing legislation did not uphold the Natura 2000 principles, and alternative legislation needed to be designed instead. The following judicial crisis led to an immediate suspension of thousands of building and construction projects, as these projects also emit nitrogen. The government needed to act swiftly, otherwise essential parts of the country would come to a standstill. One of the new ad hoc laws, introduced just before Covid-19, was a speed limit reduction to 100 km/h at motorways during daytime.

Reducing animal numbers

That was only the beginning. The Dutch cabinet is currently aiming for a reduction of nitrogen emission levels of 50% by 2030. The main culprit is thought to be (animal) agriculture. Scientific reports showed that of all nitrogen emitting industries, a relatively large part comes from animal production. Bring down the numbers of animals, they said, and you bring down nitrogen emission levels. Politicians are making plans to strongly reduce animal numbers in farms located close to Natura 2000 areas. For producers in those areas, continuing with a fraction of the original amount of animals is not really an option, so complying with legislation would be equal to stopping altogether.

In all the 45 years of my life, I have not seen a topic that is so nationally divisive as the current nitrogen crisis

Way of living threatened

With 162 Natura 2000 areas, it is no surprise that many farms in one way or another see their current way of operating be threatened. And with these farms, the surrounding villages and wider countryside see change become imminent.

That was the moment when the brew in the cauldron started bubbling and began to emit alarming smells and sounds. In all the 45 years of my life, I have not seen a topic that is so nationally divisive as the current nitrogen crisis. More than once, farmers went up to The Hague, seat of the Netherlands’ government, in protest. All over the countryside, national flags have been displayed upside down, to express anger and desperation. This summer, motorways and retailer distribution centres were blocked. Governmental calculation models are being called into question, ministers are considered incompetent and another new political party is growing steadily in the polls – the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB). In the countryside, a vast amount of people sympathise with the farmers’ protests.

Get the Netherlands building again

On the other side, however, there is no longer “just” a green environmentalist and welfarist minority wanting to change animal agriculture. The movement has grown to include a larger part of society, that wants to comply with legislation, with European rules, wanting to get the Netherlands picking up construction again, wanting the stalemate to be over whilst a shortage of homes causes prices for houses to go sky-high. “Why do we need to be the world’s number #2 in agricultural exports?”, they ask. And at the heart of all that, there continues to be the uncompromising activist zeal wanting animal agriculture to be over – or extensified at best.

Negotiations do not seem to lead anywhere. Somehow meeting each other half-way – the old-fashioned Dutch approach of solving problems – does not seem to be possible.

Existential fears are justified

I have no idea where this all will lead to on the short term. My heart and mind are with our farmers, as well as the wider countryside communities, whose existential fears are justified, as overly drastic governmental policies may damage countryside life beyond repair. Those in favour of rapid change preach it will change for the better – but once it has changed, there is no way back. I fear for what we will lose.

Those opposing change pray the government will fall, hoping that all plans will be off the table. I think, however, that it only means putting a lid on the pot with the sizzling soup. It does not make it go away. The conflict with EU legislation will continue to exist. On top, there are additional challenges about fertiliser application (derogation) as well as water quality waiting in the not-so-imminent future.

Stamp-size country hitting the limits

To me, it all fits in a picture of a stamp-size country hitting the limits of its growth, with an ever-growing population and continuing urbanisation. The future will only hold more battles for space, with increasing tensions what to do with the land and how to do it to the best of our abilities. In a democracy, the majority decides, and that majority lives in ever-growing cities these days.

All I genuinely hope for is that the Netherlands, on its road to solving this “nitrogen crisis,” as well as other agricultural issues, can start again at square one. Rushing through legislation by pushy policies leads to unparalleled levels of anger, solving exactly nothing. I hope a future government will choose to find a road based on compassion and cooperation, with everyone involved.

Only then, the future cauldron can serve a delicious stew which everyone will enjoy.