Optimistic vs pessimistic pigs

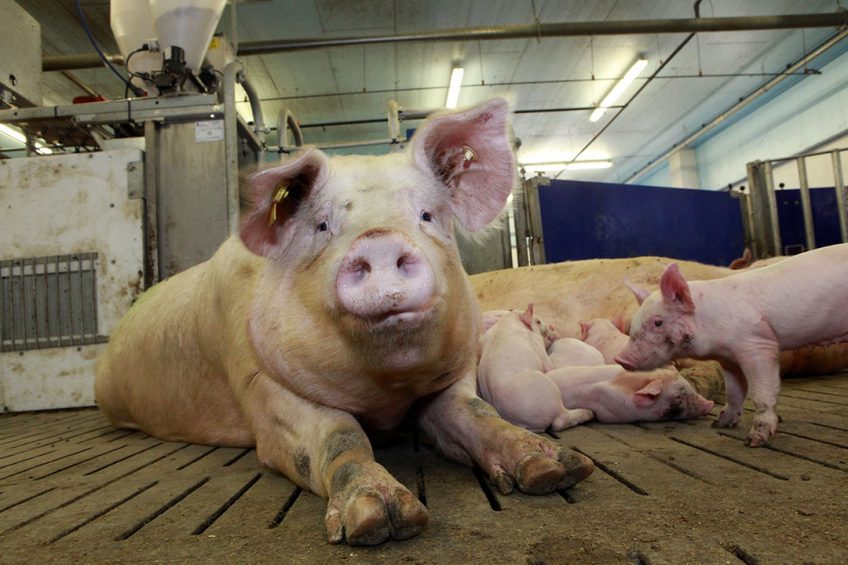

Can pigs actually be optimistic or pessimistic? Or is it even possible to assess pig feelings? There has been some serious research going on into these questions. Pig welfare and health expert Dr Monique Pairis-Garcia describes how these types of trials help to push the boundaries of science.

The ‘3 schools of animal welfare’ have been one of the main foundations in assessing livestock welfare on-farm. These schools include evaluating an animal’s welfare based on it biological functioning, natural living and affective state.

- The school of biological functioning focuses on evaluating the physical health and productivity of the animal as a means to assess welfare.

- The natural living school focuses on the animal’s ability to perform natural, species-specific behaviours, particularly those in which they are highly motivated to perform.

- The last school of welfare, affective states, focuses on assessing the subjective emotional experience of the animal as a means to truly understand what the animal is experiencing.

Use of feelings to assess pig welfare

Historically, there has been criticism regarding the use of feelings/affective states to assess animal welfare. Some scientific camps believed that it was not our ethical obligation to assume responsibility of an animal’s affective state while others believed that subjective experiences fall outside the scope of scientific investigation.

However, in the last 10 years, more work has been dedicated to understanding what the animal is experiencing as a means to measure welfare. This has been accomplished by using animal motivation and preference as a tool to determine what an animal wants and prefers. Studies evaluating motivation and preference have been conducted by either giving an animal a choice and observing what resource it chooses, or developing tasks in which the animal has to exert work to gain or avoid a resource.

Cognitive bias test for pigs

More recently, scientists have delved into utilising cognitive bias to better assess an animal’s physical and physiological welfare. The cognitive bias test, used by Dr Tina Horback of UC Davis, evaluates the judgement of an animal and measures how emotional/affective states of the animal can effect cognitive processes and decision-making.

This concept, defined most commonly in humans as the people viewing a situation with a glass half-full or half empty, can help shed light in understanding how the state of an animal’s welfare can influence how they may view or perceive a situation. Dr Horback conducted a cognitive bias assessment in commercial sows during her time at the University of Pennsylvania, New Bolton Center. In this study, Dr Horback evaluated the capacity for a sow to be trained to a spatial task in which they either received feed in one location or did not receive feed in another location.

Read more expert opinions in our special section at Pig Progress

Sows provided with empty bowls

Once training was complete, sows were provided with an empty bowl in between the 2 previously trained locations. Sows that approached the bowl anticipating feed were considered optimistic, while the sows that did not approach the bowl were viewed as pessimistic. Sows categorised as optimistic were identified to be the more dominant sows of the group, while submissive sows tended to demonstrate a more pessimistic viewpoint of the feed bowl.

These types of studies not only help push the boundaries of science but encourage the scientific community to go beyond our traditional measures of welfare and start answering question specific to what the animal is experiencing.

Need for more welfare assessments

This work highlights the need for welfare assessments to expand beyond the health, productivity and behaviour of the animal and explore the psychological factors that positively and negatively influence an animal’s welfare. In addition, this work highlights the value of understanding how animal personalities can influence the success and productivity of animals in commercial settings.