The genius who solved the porcine ileitis puzzle

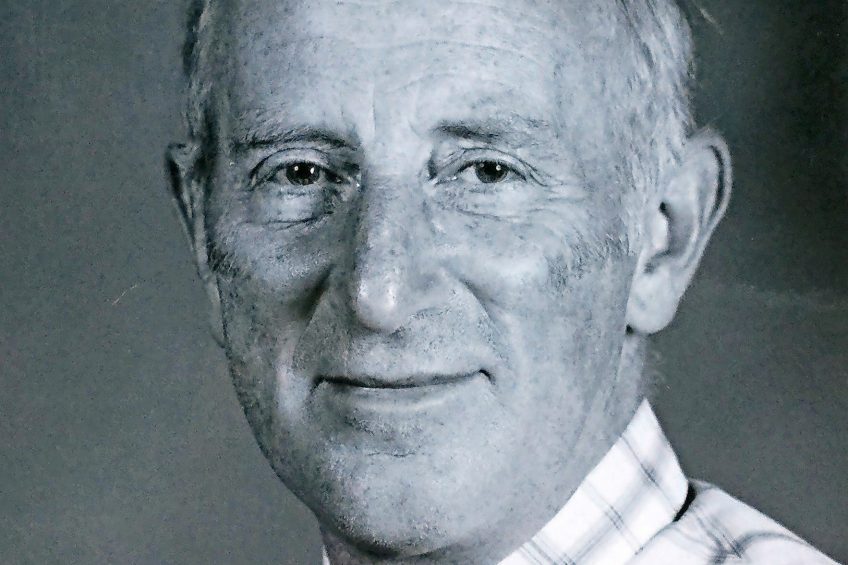

Ever wondered why ileitis in pigs is caused by a bacteria called ‘Lawsonia’? That is because the pathogen was first described by the Scottish veterinary researcher, Dr Gordon Lawson. Sadly he passed away early 2018 – reason to look back and reflect.

Dr Gordon Lawson died in January 2018, at the age of 86, after a short illness. He was a brilliant microbiologist, and a modest man, despite a distinguished professional life in veterinary research and teaching, culminating in recognition of his scientific excellence through his appointment as head of veterinary pathology and ‘reader’ at the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies (RDSVS).

Today, thanks to the work of Dr Lawson and many of his colleagues, the RDSVS is considered a top-class veterinary school, attracting major funding, internationally-renowned scientific staff and high quality students. The RDSVS is now based at the renovated Easter Bush Campus, near Edinburgh, Scotland, the location of most of the porcine ileitis work carried out during the 1970s and 1980s, and now a state-of-the-art research hub that incorporates the Roslin Institute, of ‘Dolly the Sheep’ fame, the first cloned mammal.

Brilliant post-graduate student

Dr Lawson started his scientific career with a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture from Edinburgh University, followed by a veterinary degree at the RDSVS, universally known as the ‘Dick Vet’. He achieved his PhD in pig Salmonella from Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland, where he was recognised as one of the brightest post-graduate students of his generation.

After a few years in large and small animal veterinary practice in Inverness, Scotland, he returned to Northern Ireland for a decade with the UK Ministry of Agriculture Veterinary Services as first, research officer and then senior research officer.

In 1966, he joined the pathology department of the Dick Vet, where he remained until his retirement in 1996. During his 30 years at the Edinburgh school, Dr Lawson made outstanding contributions to veterinary microbiology, starting with the development of high quality bacteriological services to the pathology department and to the local veterinary and farming communities, as well as excellent ‘hands on’ microbiology teaching programmes for countless undergraduate and post-graduate students, and culminating with his internationally recognised scientific investigations on the porcine ileitis disease complex.

Porcine ileitis

Porcine ileitis is recognised today as an infectious disease of pigs (and other species, including horses), caused by Lawsonia intracellullaris, an organism that is responsible for a number of gut-related pathological syndromes, including post-weaning ill-thrift in growing pigs, as well as explosive haemorrhagic enteritis in Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) herds.

The porcine ileitis story began in the early 1970s, when a PhD programme using hysterectomy-derived pigs suffered a crushing outbreak of a haemorrhagic enteric disorder, never before recognised or described. The Dick Vet had just installed an electron microscope, and mucosal cells from affected pig ilea were examined by the pathology and anatomy departments, who together recognised the presence of ‘organelles’ not of mammalian cell origin. Thus began a ‘crime scene investigation’ lasting nearly two decades, and culminating in the identification of those ‘organelles’ as Campylobacter-like organisms, but not Campylobacters, and reproduction of porcine ileitis using cell-cultures of the ‘organelles’.

In fact, the porcine ileitis disease complex is caused by an obligate intra-cellular bacterium, Campylobacter-like in morphology, Lawsonia intracellularis, see also the pictures.

Another causative agent

Dr Lawson’s brilliance was in the recognition that, despite the presence of considerable numbers of Campylobacters in lesions of porcine ileitis, mainly Campylobacter sputorum ssp. mucosalis, which are usually found in the oral cavity, the disease could not be reproduced with Campylobacters, and hence another causative agent was the most likely culprit. Dr Lawson and his team of PhD students were responsible for the painstaking development of tissue culture techniques that enabled growth of those intra-cellular bacteria, and later successful reproduction of the disease.

It is now known that Lawsonia intracellularis infection is spread from pig to pig via infected faeces, usually between pigs at mixing. As the organism can survive for short periods outside the pig, transmission can occur indirectly following the consumption of contaminated feed and water or by moving susceptible animals into contaminated pens or vehicles.

The organism can persist in mice, and these and other species may represent a source of infection for swine. Clinical disease is most commonly seen in recently-weaned pigs and lasts for about six weeks. Porcine ileitis has an incubation period of three to six weeks and can occur in animals at any age from three to four weeks to adults.

The first signs are failure to gain weight or loss of weight and varying degrees of inappetence. Affected pigs appear thin, pale, may vomit, are anaemic and may have blackened faeces due to the presence of black, altered blood. Some animals pass loose granular faeces, which spread on concrete like pools of wet cement, especially where infections with organisms such as spirochaetes are also present. After four to six weeks affected pigs may recover completely.

Haemorrhagic enteropathy

Some animals die suddenly at this stage with proliferative haemorrhagic enteropathy, probably an extreme immune reaction to Lawsonia intracellularis infection. These pigs usually appear pale with a low body temperature (37.8ºC, 100ºF) one to two hours prior to death and could be any age from six to ten weeks and upwards. Adult breeding stock may die suddenly from proliferative haemorrhagic enteropathy when the disease first enters a herd.

About 12% of a newly infected herd may be affected and 6% may die. Some recovered animals remain stunted. They may appear thin, pale and may have mild diarrhoea. These are the animals most likely to have developed necrotic enteritis, which is necrosis of the hyperplastic gut mucosa typically seen in the earlier stages of infection. Lawsonia intracellularis can be identified in faeces by the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique and antibodies against Lawsonia intracellularis may be detected in the blood of infected swine herds.

Post-mortem examination of pigs

Proliferative enteropathy can be confirmed at post-mortem examination of affected pigs. They are usually pale and may be in poor condition. The terminal ileum is thickened, pale and its lining is contorted into folds, which resist stretching. Parts of the large intestine may also be affected. There may be clots of blood in the affected bowel and this blood appears black once it reaches the large intestine. Gastric ulceration is absent.

The affected gut lining can be covered with dead tissue in the stage of the disease known as necrotic enteritis. Laboratory tests confirm the presence of the disease or infection. Characteristic hyperplastic changes in the cells of the intestinal lining can be seen by light microscopy. The organisms can be demonstrated in mucosal enterocytes via light microscopy of silver-stained samples, as well as by electron microscopy. Lawsonia intracellularis can be isolated from affected mucosal cells, and its identity confirmed.

Cracking the porcine ileitis puzzle

Dr Lawson’s contribution to cracking the porcine ileitis puzzle is an amazing feat of research in microbiology, especially taking into consideration the relative absence of sophisticated molecular tools in the 1970s and 1980s. Much of the work was achieved with standard microbial and cell culture techniques, supported with basic pathology – gross necropsies, histopathology, silver-staining techniques, and electron microscopy.

Lawsonia intracellularis, the pathogen, has many features in common with its namesake, Gordon Lawson, a complex, creative character and a hard nut to crack, but at the same time a resilient and persistent life-form, with considerable intelligence and beauty.

In his private life, Dr Lawson was a devoted husband and father, who enjoyed solitary and peaceful pursuits such as windsurfing across the chilly waters of St Mary’s Loch, near his home in Peebles, Scotland. He was also an accomplished painter of beautiful and precise watercolour landscapes. His eye for detail extended from his professional to his private life.

Today, there is a live oral vaccine for porcine ileitis, administered as a single dose in the drinking water to pigs of three weeks of age or older. The vaccine is based on an avirulent strain of Lawsonia intracellularis. In clinical studies, this vaccine is proven to significantly prevent gross and microscopic intestinal lesions of ileitis and to significantly reduce colonisation of virulent Lawsonia intracellularis after natural challenge. Whereas the successful development of such vaccines is always a team effort, all who knew and worked with Dr Lawson recognise his major contributions to the investigation and control of the porcine ileitis disease complex, and thus to improved pig health, welfare and performance.

Illustrating life trends

Dr Lawson never pursued immortality. He was a modest man. However, he has achieved immortality in his great discovery, Lawsonia intracellularis. On behalf of Gordon Lawson, the authors would like to thank the army of academic colleagues, scientists, technicians, photographers, librarians, statisticians, post-graduate students, secretarial and administrative staff who contributed in ways too numerous to mention to solving the porcine ileitis puzzle and thus helping to identify, control and prevent a major enteropathogen, responsible for both insidious losses to the pig industry (porcine intestinal adenomatosis) as well as acute disease outbreaks (proliferative haemorrhagic enteropathy).

References available on request. The authors can be reached at rowlandac@tiscali.co.uk and elinor@pentec-consulting.eu. The RDSVS porcine ileitis project was funded by the UK Agricultural Research Council.