Finding the best moment to bring pigs to market

Balancing feed costs with the optimum market weight of finishing pigs is a daily decision for pig producers. What the human eye cannot yet see, a computer model can. Using the latest prediction models has been shown to increase operational profits.

Raising pigs is not a linear process. It is dependent on many variables such as genetics, diet, housing and local market conditions. The quest is to find the right balance in managing all the input costs a farmer has (such as feed price) against the price paid for a certain carcass weight – and against quality.

This comes down to finding the right moment to sell. When pig feed prices are high, the animals can be marketed earlier at a lower carcass weight. When pork prices are good, it could make sense to keep the pigs longer on farm and market them heavier. It is part of the daily decision process of pig producers around the world. While market conditions are difficult for individual pig producers to control, farmers can control their feeding strategies or delivery moment of the pigs. And that is where savings can add up.

More information available

Pig producers around the world have become more tech savvy and use farm and animal data to better manage marketing of pigs. Yet, in practice, it is logical that decisions are still partly based on experiences and learnings from the past. But there is now more information available that farmers can use for daily decisions, which is an untapped potential for increasing operational profits. Some farms use the all-in, all-out method, and while this is one of the best strategies to minimise the spread of infectious diseases, it can lead to variation in weight when all the pigs are sold at the same time.

Guesswork costs money

This variation can be huge. At the same age, some pigs get stuck at 80 kg, while fast growers will reach 120 kg. But they will all be sold at the same time. Another common strategy is to have mixed batches of slow, middle and fast growers. The fast growers will be marketed first, making room for the others to fully grow out. And even though the pigs are weighed during the fattening period, the selection of animals (moment of selling and number of pigs) is still often based on experiences and the human eye. When the farmer receives the data sheet back from the slaughterhouse, differences in carcass weight, lean meat and fat percentages become clear and might be different than expected. This in turn leads to adjustment of the feeding strategy or selection for the next round, which takes time and money.

Homogenous batches

Pigs with slow growth within a batch are usually responsible for a non-efficient use of the growing and fattening facilities. The aim for all pig producers is to prevent the variety and come as close to homogenous batches as possible. To have this certainty, knowing the effect of certain inputs (such as the diet) on the overall growing–finishing period is important. And this is where the decision-making models come in.

Swine prediction in practice

Watson is Trouw Nutrition’s decision-making model for swine that allows farmers to predict multiple items, including the best marketing strategy, based on different price scenarios for feed and pork prices and the feed formulation (and protein and energy density levels of the diet) all at the same time. Modelling is based on the unique animal and farm data coming from the feed management system, combined with slaughterhouse data on meat quality and carcass weights.

Different scenarios

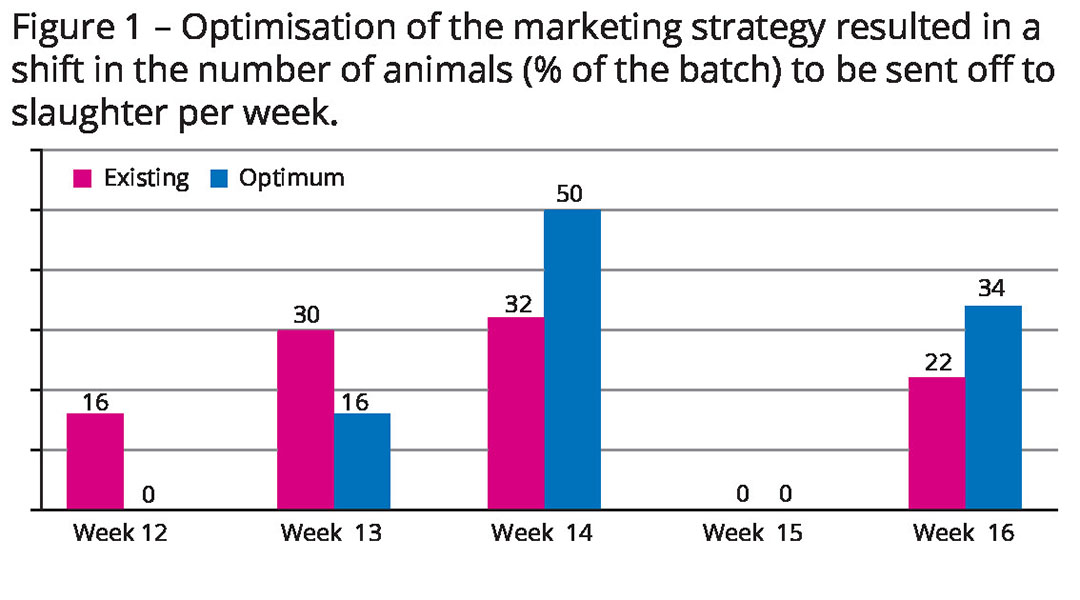

The model can then run different scenarios for the farm based on low, medium or high feed prices and pork prices. The potential savings that can be established by modelling and the application of a certain diet were clearly shown at one of the company’s client farms. Based on the input of this swine producer and the market conditions at the time of calculation, the model showed that this farm was selling too many animals too early. Before, 16% of the pigs were sold in week 12, 30% in week 13, 32% in week 14 and 22% in week 16. Using Watson, it was shown that the farmer could instead send 16% of the pigs in week 13, 50% of the animals in week 14 and 34% in week 16 (Figure 1).

Optmising several elements at the same time

That optimisation exercise resulted in extra profit of € 1.80 per pig and more uniform batches. In total, this farm had an extra profit of € 13,300 per year. And that can be even more when several elements on a farm are optimised at the same time (nutritional rebalancing, management, review of animal marketing). It is possible to create a compounding effect of cost savings along the way, which can add up to several euros per pig as extra profit and extra margin for the pig producer.

Accuracy becomes prerequisite

When decisions are unfounded, based on trial and error or simple guesswork, it can not only compromise animal health and performance, but also have large financial impacts on the total swine operation. Considering that pig farms are getting bigger in size (with multiple locations) and market conditions remain volatile and unpredictable, the impacts of wrong decisions are increasing. This is why pig producers need straightforward options for what to do when conditions change. And they cannot rely any longer on assumptions and experiences from the past as valid indicators for important decisions.

Models have become better and more complete

The prediction model can advise on which variables have a certain outcome. And although modelling is not a new thing in swine production, models have become better and more complete. This allows access to an advanced prediction model that considers all the factors influencing production outcomes – including genetics, environment, health, feed, shipment and sustainability – into a single package. It’s possible to see that an increasing number of feed and farm consultants use these models to give solid and informed advice to farmers.

As with any prediction or calculation, it is always up to the farmer to implement the recommendation from the calculation model or change to a different feeding regime or feed formulation. Yet, overall, the model provides 95–98% accuracy compared to practice, which is tremendously close to reality.