Lawsonia can impact other gut pathogens

A growing body of evidence is finding gut health a factor that must be prioritised to allow the pig to achieve its full genetic potential as well as be less susceptible to not only enteric but also respiratory disease. Having tools to promote a healthy gut is very important in order to achieve maximum efficiency and overall health on the farm.

Research has led to interesting findings on how ileitis, caused by the bacterial pathogen Lawsonia intracellularis, can compromise gut health.

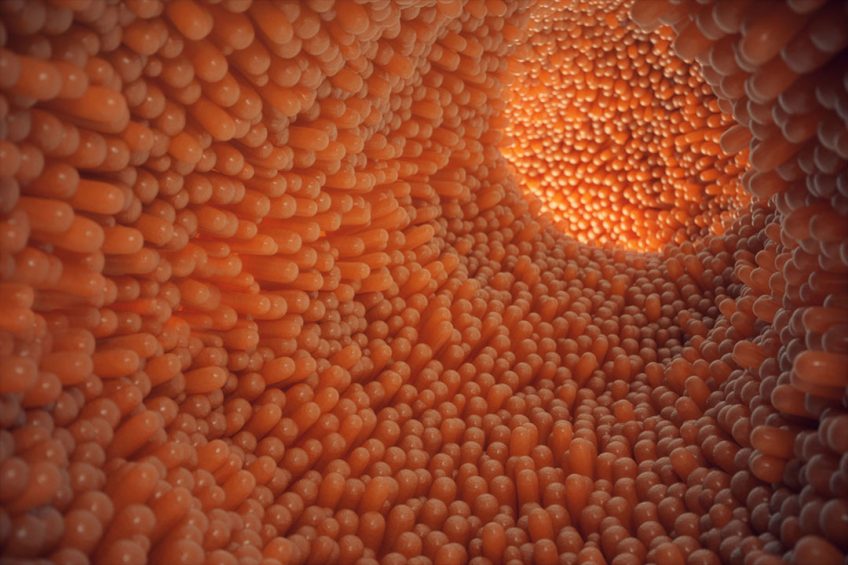

The hallmark lesion of ileitis is the thickening of the intestinal wall, typically in the ileum but in any portion of the intestinal tract. The intestine is lined with cells called enterocytes. These cells are responsible for the absorption of the nutrients that will lead to weight gain. Enterocytes are present in both villi and crypt structures in the intestine.

Lawsonia infects enterocytes in the crypts. What causes the thickening of the intestine is the increase in the number of enterocytes in the infected crypts. Unfortunately, they are not the enterocytes that promote the absorption of nutrients – those are the mature enterocytes found in the villi.

Researchers at University of Minnesota, USA, have found that receptors to important nutrients like amino acids, glucose and lipids are decreased in enterocytes infected by Lawsonia. Importantly, infection also leads to a decrease in goblet cells which are responsible for producing the mucus that separates bacteria from the enterocyte lining of the gut. Research from the University of Edinburgh, UK, confirmed this and found that infected pigs have a decrease of the important protective mucus layer.

Recently, the team at the University of Minnesota also found that not only are the crypts enlarged and goblet cells decreased with infection, but also villi height can be decreased as well. This is a problem since a decrease in villi height would be expected to have a direct impact on the capacity of the pig to absorb nutrients.

The research team also analysed the genes of infected tissue in a model of subclinical infection in which animals did not present many clinical signs of diarrhoea. The scientists found that several pathways and genes associated with increased cell proliferation and inflammation were activated, especially in animals with more severe lesions. These investigations show that Lawsonia-infected intestines are far from those of a normal functioning and healthy intestinal tract.

Economic impact of infection

On the farm, Lawsonia infection can lead to costly lesions. Estimates of the impact of infection range from a 6 to 20% loss in average daily gain, an increase in feed per unit gain of 6-25% as well as more days needed to reach market weight and increased variation among animals.

Implementing oral live vaccination has been found to be effective in preventing these losses in different regions of the world. In the United States, several studies have found a significant improvement in average daily weight gain and a reduction of both macroscopic and microscopic lesions to infection.

The vaccine has also been found to help prevent the acute haemorrhagic form of ileitis. For more than ten years, these findings have been reproduced around the world along with significant improvement in performance measures. Recently, in Finland a field study showed that vaccinated pigs sent to market were on average 3.57 kg heavier than non-vaccinated pigs.

Lawsonia: Response to other pathogens

Not only can Lawsonia infection directly impact performance, but it may also increase susceptibility to other pathogens. The pig gut is colonised by an array of micro-organisms known collectively as the microbiome (or microbiota). The bacteria in this community can have different relationships amongst each other as well as with the pig host. A healthy gut is one with a bacterial community that allows for proper intestinal function and promotes colonisation resistance to pathogens, which ultimately leads to optimal production performance. Lawsonia seems to lead the microbiome in the opposite direction.

An epidemiologic study conducted in France found that Lawsonia was a risk factor for increased Salmonella shedding in growing-finishing pigs. With this in mind, the researchers at the University of Minnesota investigated if prevention of Lawsonia with an oral live vaccine could impact Salmonella shedding. In addition, it was investigated if changes in the microbiome (bacterial community) in the gut could be involved in this response. To test that, four treatment groups were compared. They were challenged with either Salmonella Typhimurium alone or with L. intracellularis, with and without L. intracellularis vaccination.

Vaccination of the co-infected pigs significantly decreased their faecal shedding of Salmonella at seven days after the S. Typhimurium challenge. At this stage significantly fewer pigs in the vaccinated/co-infected group – just 38% compared to 100% of pigs in the other challenged groups – were actively shedding Salmonella and this trend persisted at later time-points. At seven days post Salmonella challenge, co-infected pigs shed around 100 times more Salmonella than the group co-infected that had received oral live vaccination. The effect of vaccination on shedding of Salmonella was only present in co-infected animals suggesting that it was mediated by the effect of the vaccine on Lawsonia infection in the gut.

When the microbiome response of animals was analysed at the seven day time-point, the research team found that the co-infected vaccinated group had a different bacterial community than those of the co-infected group that had not received vaccination. Among several differences, Clostridium butyricum was much more abundant in the group that had received the oral live vaccine as compared to those in the co-infected non-vaccinated group. C. butyricum is known for producing butyrate, which has anti-inflammatory properties and also can hamper the invasion of Salmonella in the gut.

Fewer animals shedding Salmonella in faeces

Interestingly, a recent study from the University of Veterinary Medicine, Hanover, Germany found that when comparing tylosin treatment to oral live Lawsonia vaccination, in animals co-infected with Lawsonia and Salmonella Derby, the vaccinated group had significantly fewer animals shedding Salmonella Derby in faeces and significantly fewer pigs with positive cultures from ileo-caecal lymph nodes. These findings are important, as they show oral live vaccination may be an alternative to antimicrobials to help control Salmonella and improve food safety.

The above-mentioned research team from the University of Minnesota also found that Lawsonia can have an additive effect on the induction of inflammatory markers that contribute to the pathology of S. Typhimurium in co-infected enterocytes. This suggests that the host response to infection, in addition to changes in the microbiome, may be how these two pathogens favour each other.

Researchers from University of Minas Gerais in Brazil presented results last year showing a synergistic effect in pigs co-infected with Lawsonia and Brachyspira hyodysenteriae. Co-infected pigs presented more severe disease as compared to each infection alone. That enhancement again could be due to changes in the microbiome mediated by Lawsonia or its influence in the gut’s response to the subsequent infection. It would be interesting to investigate if vaccination against Lawsonia could influence the response to B. hyodysenteriae in co-infected animals, as it could likely have an impact based on research conducted with Lawsonia and Salmonella co-infection.

The knowledge of how Lawsonia can affect the gut by disturbing its function, structure, microbial community composition and interaction with other pathogens is increasing. This is further proof of the importance of preventing this costly disease.

References available upon request.