Supplying organic selenium: Source-dependent benefits

Not all sources of selenium are created equal – this much is clear. The bio-availability of the mineral depends on the way it is offered to a pig. Organic forms of selenium are the optimal nutritional source, but even within organic forms there are various possibilities.

Ever since its initial discovery in the early 1900s, selenium has presented a nutritional conundrum due to its dual status as a potentially toxic but highly essential trace element. The form in which selenium is presented is the main determinant of its efficacy. Selenium supplements are available in several forms, including:

inorganic mineral salts such as sodium selenite or selenate;

selenium nanoparticles, produced predominantly through chemical reduction of inorganic compounds;

organic forms, such as selenium-enriched yeast, in which selenoamino acid analogues such as selenomethionine (SeMet) predominate; or

chemically synthesised selenoamino acids and selenoamino acid analogues produced by synthetic routes.

Organic vs inorganic

The largest differences are noted between inorganic and organic forms of the element. While inorganic sodium selenite has historically been the most common source of selenium added to feed, studies have found that inorganic selenium has a high toxicity and its absorption and conversion rates are low. Organic selenium has been found to be a more effective source, resulting in an increased number of live young per animal, the stimulation of immune function, overall improvements in animal health and an enhanced shelf life for meat, milk and eggs.

While these observations can be attributed to general enhancements in cellular antioxidant status and the improvement of the effects of oxidative stress, the exact mechanisms by which the effects are mediated remain unclear. However, peer-reviewed research has clearly shown that dietary intervention with organic selenium is a key element for significantly enhancing production and supporting better animal nutrition, health and well-being across multiple species.

The distribution and accumulation of selenium in animal tissues depends greatly on the type of selenium supplement offered. The form in which the selenium is presented will play a crucial role in its bioavailability and efficacy. Organic forms of selenium are the optimal nutritional source.

Selenium absorption occurs within the small intestine. Inorganic selenium forms, such as selenite, are absorbed inefficiently, mainly by passive diffusion. The organic SeMet is absorbed using efficient methionine transport mechanisms and transformed into common seleno-intermediates for further utilisation and/or excretion. Following absorption, SeMet can be incorporated non-specifically into general body proteins in place of methionine and can even act as a biological pool for selenium, to be utilised during periods of suboptimal selenium intake.

Strain-dependent effects

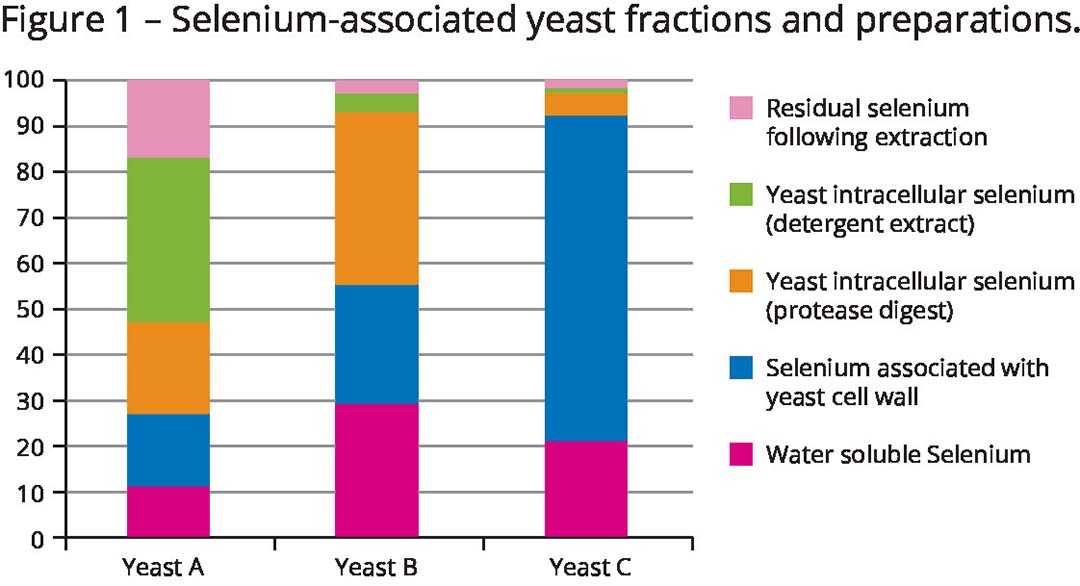

It is well-accepted that even closely related yeast strains have their own unique biochemical and genetic characteristics. Numerous peer-reviewed research papers have been published on this topic. One such study examined three commercial preparations of selenium-enriched yeast and assessed the composition of each product in terms of how much selenium was deposited within individual yeast fractions (see Figure 1).

Although there is a very common perception that all selenium yeast preparations provide the same benefits in the same ways, it is clear that the location and storage of selenium within yeast is totally different between strains. Considering these differences, it is reasonable to expect that these products will also differ in parameters, such as shelf life, bioavailability and, indeed, toxicology. Rather than viewing these products in exactly the same light, we must see them as distinctly different selenium preparations.

Digestibility is the key

In the case of organic selenium products, such as selenised yeast, biological efficacy is more dependent on the digestibility and accessibility of selenium-containing proteins and peptides present in the preparations. In the feed industry, there is a misconception regarding the total SeMet content of selenium-enriched yeast, with the belief that “more is better.”

Peer-reviewed research has addressed this issue by assessing the digestibility of selenium-containing protein and peptides in selenium-enriched yeast products following in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion.

The results indicated that the available selenium yeast products varied considerably in terms of digestibility, with notable differences observed between them in the levels of bound and free SeMet following simulated digestion.

Clearly, not all organic selenium sources are created equal in terms of their bio-accessibility or indeed their effectiveness. Not only are there differences in terms of the digestibility of selenium-containing proteins and peptides, but increasing the relative SeMet content does not necessarily increase the bio-availability of the selenium source. Ultimately, consideration needs to be given to the variations that exist in the bio-availabilities of individual products, in the digestion and liberation of selenoamino acids such as SeMet, and in their ability to act as pro-oxidants.