Large scale vaccination against swine flu (Part I)

Pigs are known as mixing vessels for influenza strains. Keeping flu under control in pigs should also indirectly benefit human health. Vaccination of pigs could therefore contribute to averting the next global influenza pandemic. So why is that not happening?

In January 2009, a novel strain of influenza A virus is believed to have emerged in pigs in central Mexico. The strain, known as (H1N1)pdm09 virus, contained a unique combination of influenza genes not previously found in the same virus. It was able to jump species and infect people and proved to be capable of human-to-human transmission. It rapidly spread from Mexico, first to the United States and within a few months to 74 countries across the world. The WHO declared a global influenza pandemic. A year later, when the pandemic was declared over, it was estimated that more than half a million people had died, with 80% of deaths occurring in people under 60 years of age.

A different virus

The (H1N1)pdm09 virus was different from any other influenza A strains circulating at the time. While young people tended not to have any existing immunity to the new virus, around a third of over-60 year olds had antibodies against this virus, most likely due to being exposed to a different strain of H1N1 virus in the past.

The seasonal flu vaccines being used that year provided little protection from the new strain. Although a vaccine against the pandemic (H1N1)pdm09 virus was produced, when it eventually became available in November 2009 the peak of the pandemic was already over. However, the H1N1 virus continues to circulate as a component of the global seasonal flu burden, which usually causes several million cases of severe disease and several hundreds of thousands of deaths each year.

Europe’s pigs could be a source

A recently published peer-reviewed study, based on surveillance work funded by Ceva, suggests that Europe’s pig herds represent an increasing risk of being the source of the next pandemic influenza virus. The study, for which pigs with respiratory problems were sampled from 2,500 farms in 17 European countries, revealed that there was a year-round presence of up to 4 major lineages of swine influenza A viruses.

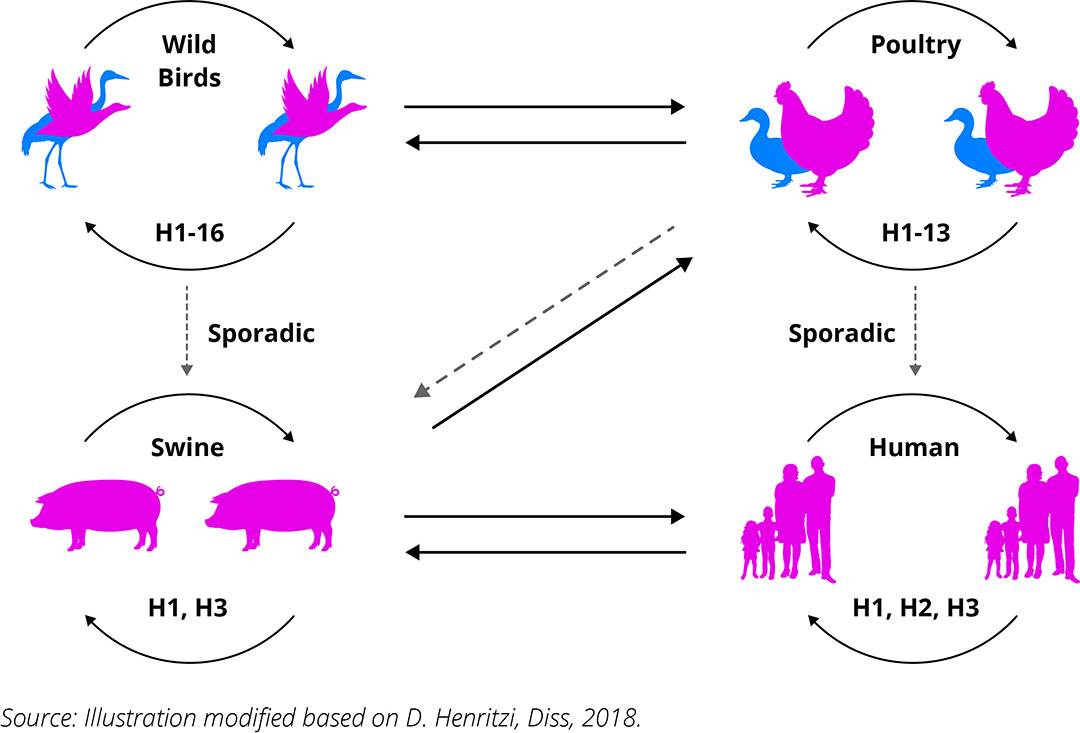

Pigs can become infected with strains of influenza virus from other pigs, birds and people. These strains can then mingle within the pigs where there is the potential for reassortment of the individual strains’ genetic material, giving rise to novel strains. That is presumably what happened in Mexico in 2009. The recent study demonstrated that intensive reassortment of swine flu lineages together with human pandemic virus has produced at least 31 distinct genotypes in pigs, including some that have characteristics associated with the potential for zoonotic transmission (i.e. to infect people).

The authors of the recent paper concluded that European swine populations serve as reservoirs for emerging influenza strains that have the potential to infect people and, perhaps, go on to cause pandemics. Fortunately, since 2009 this has not happened.

Figure 1 – Interspecies transmission of influenza A virus. HA-subtypes that circulate in the species are given.

Management influenza in people and pigs

In people, the main tools used to manage seasonal influenza are surveillance and large-scale annual vaccination programmes targeted at vulnerable members of the population. Each year, the WHO makes recommendations for the composition of influenza vaccines in the northern and southern hemispheres. Those are based on the circulating strains of influenza A and B that have been reported by different countries that year.

In Europe, it is widely accepted that vaccination is the most effective public health intervention to mitigate and prevent seasonal influenza. The Council of Europe recommends that vaccination coverage for groups at higher risk of severe disease and complications should be at least 75%. Different countries target different groups for vaccination, but these always include the elderly and those with suppressed immune systems. In addition, some also vaccinate healthcare workers, pregnant women, children and adolescents. In practice, in 2016–17 only one European country achieved the target of vaccinating 75% of the elderly.

During seasons when the virus strains included in the flu vaccine are similar to circulating flu viruses, the vaccines are relatively effective, reducing the risk of flu illness by 40–60% among the overall population, although in years where the match is less good the effectiveness can be much lower. Nonetheless, the principle of using vaccination to protect vulnerable sectors of the human population is well established in Europe.

Greater emphasis on flu vaccinations

In the post-Covid-19 era, public health authorities are placing greater emphasis on seasonal flu vaccinations. One consequence of the lockdowns was that very few cases of flu occurred in people in the winters of 2020–21 and 2021–22. With Covid-19 still causing significant disease and hospitalisations, health authorities throughout the world are keen to prevent influenza cases taking up valuable hospital beds.

This situation in humans contrasts markedly with that in pigs. Although influenza in people is largely seasonal, occurring mostly during winter, swine flu in pigs is not seasonal and can occur year-round. So, while human influenza is controlled using a single vaccination administered at the start of the flu season in autumn, the recommendation for pigs is to vaccinate sows every four months.

Pig farmers and their vets are often hesitant to follow recommendations for mass vaccination of their herds on the grounds that they consider this to be too expensive. However, as the survey referred to above shows, pig herds in Europe are very often infected with influenza A virus. Swine flu in pigs can have considerable impacts on productivity due to both the direct impacts of the swine flu virus and also because the presence of influenza virus increases the risk of secondary infection with a range of bacterial infections. The latter means that treatment costs are higher and use of antibiotics is increased, which is highly undesirable and a risk factor in the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains.

Vaccination of pigs

Trial data have shown that the vaccination of pigs against swine flu can significantly increase productivity in infected herds. For example, in a large-scale study undertaken in Germany, herds infected with pandemic influenza A virus were vaccinated using a vaccine with pandemic H1N1 strain. Comparing before and after vaccination performance, on average vaccinated sows weaned 1.33 additional piglets per year. The rate of return on the investment in vaccination was calculated to be over 5.1:1. For a 1,000-sow farm, it was estimated this would be worth an additional income of € 28,000 per year.

In Pig Progress 38.03, a follow-up article will delve deeper into pig vaccination.

References available upon request at kathrin.lillie-jaschniski@ceva.com and friederike.schmelz@ceva.com.