Disease prevention is not growth promotion

One of the most common confusions about antibiotic use in agriculture is the difference between preventative use and growth promotion use. This article sheds a light on the two types – and explains why it is important to acknowledge this difference.

Given the global imperative to preserve the effectiveness of antibiotics, it is essential for all governments and industries to be carefully considering how antibiotics are used in livestock production, alongside initiatives in the human and environmental sectors as well.

Antibiotics for prevention

The complexity of the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) problem makes it especially challenging to solve – because of the interaction across human, animal and environmental health, the different types of antibiotics and how they work, the different ways antibiotics can be administered, and for what purpose different antibiotics are used.

This imperative to address AMR is further complicated by differences in ‘geographic, disciplinary and societal variations that affect understanding and interpretation across different countries and languages’, as one article in Nature put it in May 2017. One of the most common confusions about antibiotic use in agriculture is the difference between preventative use and growth promotion use, possibly because preventative use usually involves administration to animals not (yet) showing clinical signs of infection, and because for many uses of antibiotics there is an incidental growth response.

Preventative use

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines preventative use as ‘use of an antimicrobial(s) in healthy animals considered to be at risk of infection or prior to the onset of clinical infectious disease’, whereas growth promotion is defined as ‘the use of antimicrobial substances to increase the rate of weight gain and/or the efficiency of feed utilisation’.

The distinction is important because preventative use of some antibiotic classes – especially those not used in humans – can play a critical role in antibiotic stewardship and good animal care. For example, the European Medicines Agency allows for “the administration of the product at the same time to a group of clinically healthy (but presumably infected) in-contact animals, to prevent them from developing clinical signs, and to prevent further spread of the disease.”

A good example of this is the need to prevent necrotic enteritis in chickens, when the appearance of clinical symptoms occur at a late stage of the disease, and after which treatment is often ineffective and high rates of mortality are almost certain. Another example is when pigs are weaned, or transported between facilities – i.e. during short periods when immune systems are under pressure from changes in their environment and they can suffer from dysentery.

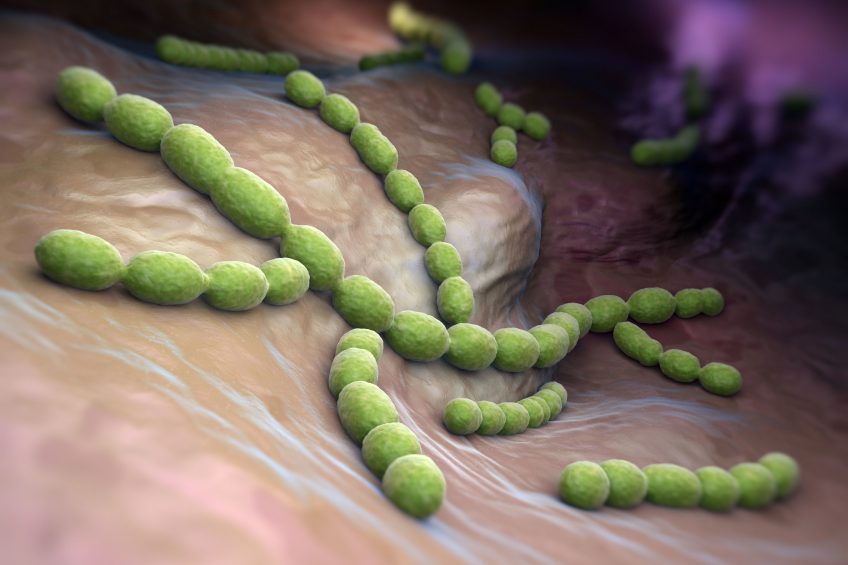

David Burch, a regular contributor to Pig Progress, explained in one of his columns that “when you have 200 weaned pigs each week you are not sure which individuals are carrying Streptococcus suis and are likely to break with septicaemia, meningitis, infectious arthritis, pericarditis and potentially die.”

If not prevented, swine dysentery requires stronger (often medically important) antibiotics to treat after symptoms have appeared, thus increasing resistance pressure on the antibiotics used.

Preventative use of antibiotics for these conditions requires administration for a defined period of time, and during a specific time in an animal’s lifecycle. Growth promotion normally involves administration at lower dose rates, and to be administered continuously – so it is also possible to distinguish between the 2 use patterns based on these practical details of administration.

Find out all there is to know about pig health using Pig Progress’ unique Pig Health Tool

Report by Australia

For example, a recent report by the Australian government explains that preventative administration is “only in the face of a potential disease outbreak or to protect animals exposed to an infectious disease, so the treatment is only required for a limited period of time… The concentration of antibiotics in the feed for therapeutic use is usually much higher than for AGP use.”

The administration of preventative antibiotics via animal feed (instead of injection) is often incorrectly assumed to be for the purpose of growth promotion. There are good reasons why preventative medication via feed produces better animal health and antimicrobial resistance outcomes than individual animal treatments after clinical infection signs appear – and this is recognised by regulatory authorities such as the US FDA, which “considers uses that are associated with treatment, control and prevention of specific diseases, including administration through feed or water, to be uses necessary for assuring the health of food-producing animals.”

For example, there are some antibiotics which are not soluble, so the most accurate dosing is achieved through mixing with dry matter in prepared feeds. Another reason is that once animals become clinically ill, they are susceptible to loss of appetite, so that they may not eat or drink, or not as much, so that dose rates can be less reliable. Individual treatment of animals during disease outbreaks also puts additional stress on the animals due to the need for handling.

No growth promotion in disguise

There are some important and practical ways in which regulatory authorities can be sure that antibiotic use for prevention, including via feed, is appropriate, and not ‘growth promotion in disguise’. First, monitoring of resistance in foodborne and commensal bacteria through harmonised laboratory surveillance will reveal levels of resistance (and therefore patterns of use), across species, antibiotic classes and geographies.

Second, monitoring antibiotic sales and use data will help to ensure correct usage per indication – i.e. if relative volumes/ species/ indication/ dose rates/ duration do not reflect appropriate use patterns, regulators will have reason to suspect imprudent use, and to act accordingly.

This is why a number of governments include monitoring and surveillance as key planks of national action plans to address antimicrobial resistance – including Australia, NZ, the US, and the EU.

Serious global concern

Antimicrobial resistance is a serious global health concern, and one of the most complex to understand, and to manage. That is why, from the G20 to the UN General Assembly, the WHO, the Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and national governments and industries around the world, there are a lot of positions being articulated, and measures taken, to ensure we preserve effectiveness of antibiotics for humans and animals. With clear and consistent approaches to risk assessment, risk management and risk communication (including clarification of the role of preventative antibiotic options), it can be successfully addressed while also taking care of animal welfare and maintaining the sustainability and security of our food for a growing global population.

References available on request.