Avoiding disease in pigs

Despite not being a vet, Pig Progress columnist John Gadd has every reason to dive into the topic of pig diseases. Two good reasons in fact, profitability and how to use the vet properly. John explains how spending extra money on prevention can in the long run be a cost saving.

1. The impact of pig diseases on profitability

After the volatility of pig price movements which we can do little about, disease has easily the most severe effect on profitability. In contrast we can do something about disease. With clinical disease, the pig shows very apparent signs which can be addressed as soon as possible – meanwhile, subclinical disease tends to be forgotten by producers because it lies hidden. While the effects are not nearly so obvious, the insidious damage it does to production over a period of time are often greater than the traumatic effects of clinical disease.

Is this true? Years of on-farm experience from before-and-after records compiled from many “How are things now?” phone calls made six months or so after the farm visit and advice given, encourages me to say that subclinical disease can be costing up to 0.3:1 on FCR (30-105 kg), equivalent to 20 kg less saleable meat sold per tonne of feed (MTF).

And for sows? The loss from subclinical disease is less easy to measure, but four piglets less per sow per year seems likely, and if unattended-to, as much as 150 kg is lopped off a sow’s lifetime productivity from a target of 500 kg reduced to 350 kg weaner weight, which plays havoc with cash flow. These losses are from the diseases you cannot necessarily see, as the pigs seem healthy. Many pig producers do not appreciate the effect of sub-clinical disease on their operations and what they can do to mitigate them.

2. Using the vet properly to avoid pig diseases

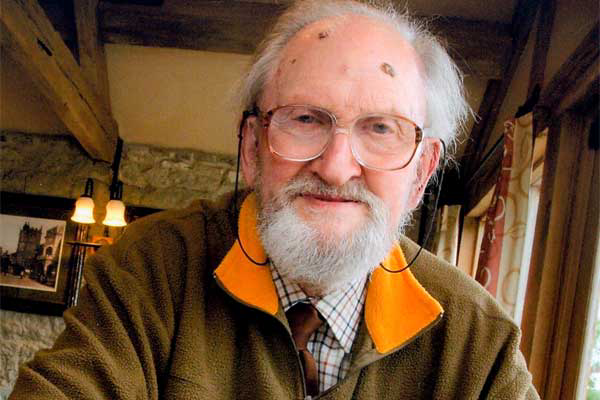

I have always worked closely with veterinarians. Early in my career I was assistant to two experienced company vets and answered queries when they were away. A good grounding in preventing and containing disease. Then for another six years I worked with a non-specialist vet on a large breeding farm where I was part of the management team. I describe this procedure below because we seemed to have got it wrong to start with. Then ten years’ experience working with a specialist pig vet on a much smaller experimental pig unit. Finally, after setting up my own pig management consultancy 30 years ago, I have worked with many pig specialist veterinary practices across the world, several of them pioneering new ideas about disease prevention. I’m still learning of course, but feel I know enough about avoiding disease to write about it!

John Gadd: “The keystone supporting the protective arch against clinical and sub-clinical disease is good immunity.”

Regular vet visits to your pig farm can save money

The first was 45 years ago, with a breeding farrow-to-finish farm of 1,400 sows selling 23,000 finished pigs per year. Of course we got disease. Because we were such a big unit, on grounds of cost we only employed a vet to come and deal with the disease storms we encountered – not as a regular visitor to monitor the disease profile. After three cases in 18 months, we employed a specialist pig practice to visit monthly, one in three of these visits just to train our labour force in disease prevention. I still have the records, as veterinary costs rose threefold which initially caused alarm, but at the end of a full year’s production, our veterinary visit costs, plus a much reduced preventative or curative medical cost, actually fell by 28%, farm income rose by 6.5% and gross margin by 11.8%. Later in my career (1980s) I was working in Canada and the USA with two pig specialist practices pioneering the routine-visit contract principle and have published what this cost the farmers and the pay backs secured.

2 factors essential to get high immunity levels for sows and piglets

The keystone supporting the protective arch against (most) subclinical diseases is good immunity. Trouble is – sows and their offspring need a high level of immunity as soon as possible. Ensuring this is done effectively by ‘thinking ahead’ reveals some gaps in many producers’ knowledge as well as capabilities – here adequate labour and farm design are the two supporting blocks either side of the immunity protective keystone.

Boosting natural immunity in grow-finishing pigs is more cost effective

In contrast to sows, for grow-finishing pigs we actually need to keep immunity levels as low as possible. To raise a high protective immune shield for growing pigs using ‘artificial’ methods – drugs, feed additives and some vaccines, costs a great deal of money. It is much cheaper to go along with nature and boost natural immunity by hygiene and better husbandry. As with sows, limitations are labour time and skills, and the buildings’ environment. Better husbandry is easily the best and least-cost method of preventing disease in grower-finishers.

For more practical information on pig production see John Gadd’s coloumns