China taking steps to reduce antibiotics usage

After years of consuming high volumes of antibiotics, China appears to be well on the way to reducing its antibiotic usage. In 2019, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture was already reporting a substantial decrease, and a recent article in The Lancet confirmed that trend.

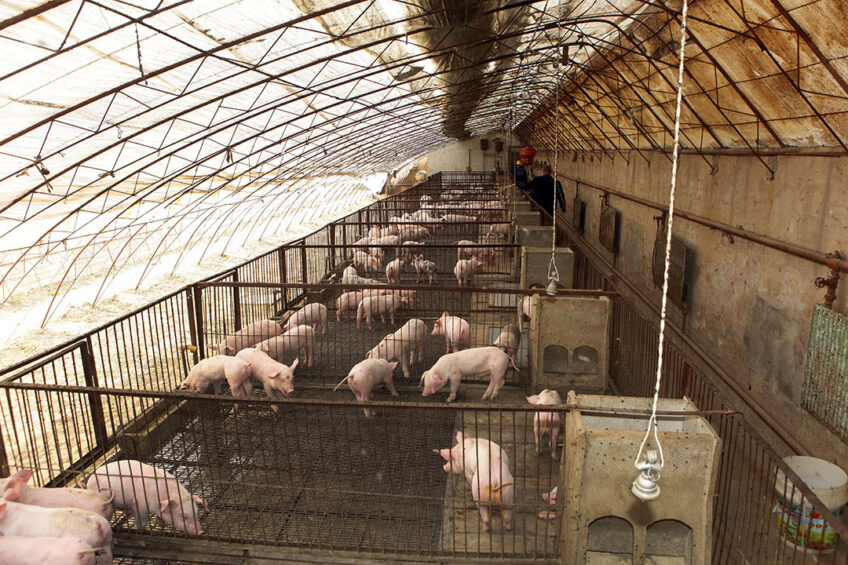

If one industry has made significant progress over the last decade in China, it must be that of veterinary medicine. Around 10 years ago, China was a huge consumer of antibiotics, and biosecurity practices were applied but not always wholeheartedly embraced.

Fast forward to 2021 and a completely new picture emerges. Obviously the presence of highly pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus as well as African Swine Fever have shown that in terms of biosecurity great strides can be taken to enhance animal health status on-farm. On top of that, the Chinese authorities have stepped up their efforts to reduce levels of antibiotic usage.

Reducing antibiotics usage

The Chinese Academy of Sciences estimated that in 2013, China consumed nearly half of all antibiotics worldwide, 52% of which – representing about 97,000 tonnes – was administered to animals, presenting a major risk factor for antimicrobial resistance.

An article in Nature reported that, in August 2019, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) had published official figures for the volume of antibiotics being used in livestock farming. According to that bulletin, between 2014 and 2018 the consumption of antibiotics in the Chinese agricultural sector had dropped by 57%, to below 30,000 tonnes.

That reduction followed tight regulations in China, although the data lack detail or explanations, the article describes. But even though such reduction has been achieved, the size of the Chinese agricultural industry means that their net consumption of antibiotics for use in livestock farming is still substantial.

Colistin a catalyst for change

Concrete data are available for the compound that was key to the change in policy: colistin. A discovery in 2015 was key to antibiotic reduction in China. A large team of researchers noticed increased reports of resistance to colistin during routine monitoring of Escherichia coli in farm animals. An E. coli strain, SHP45, that possessed a kind of resistance transferrable to other strains was isolated from a pig. The team then discovered a gene, mcr-1, that conferred more effective resistance in bacteria but was carried by a specific kind of DNA – a plasmid. This raises the possibility of it spreading to other bacteria that are already resistant to other kinds of bacteria, causing them to become “superbugs”.

On 30 April 2017, the Chinese government banned use of colistin as an animal growth promoter in an effort to control the spread of resistance. Recent Chinese research, published late 2020 in The Lancet by a large team coordinated by microbiologist Professor Yang Wang of China Agricultural University in Beijing, reviewed the patterns in colistin resistance and mcr-1 abundance in E. coli from animals and humans between 2015 and 2019 to evaluate the effects of the colistin withdrawal. The conclusion is clear: “The colistin withdrawal policy and the decreasing use of colistin in agriculture have had a significant effect on reducing colistin resistance in both animals and humans in China.”

Ban on antibiotics boosts feed additive market

The Chinese National Action Plan to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance (2017–2020) was launched to eliminate the use of antibiotics in livestock feed by 2020. It encompassed three key initiatives:

- The withdrawal of all growth-promoting feed medications except for traditional Chinese medicine. This intention was turned into legislation on 1 July 2020. From that date no feed could contain antibiotics; they can only be used to treat diseases;

- The revision of product quality standards so antimicrobials are used only for prevention or treatment, but not for growth promotion; and

- The approval of antimicrobials only for veterinary medicine, not for veterinary medicine additive purposes.

Promoting growth without resistance risk

Since the ban on antibiotics, many companies have focused on producing products to promote growth and boost animal health without the risk of antimicrobial resistance. Rabobank researchers Jingyan Sun and Chenjun Pan think that this focus on innovation and change will remain, and feed players who can change the following aspects of their business will gain in the market:

- Upgrading feed formulation: Raw material composition and nutrition ratio are key for antibiotic-free feed. Meeting the needs of animals at different growth stages will become more important, and companies will have to adjust the protein content to reduce the abnormal fermentation of undigested protein in the hindgut, which is harmful to intestinal health;

- Investing in R&D and substituting antibiotics. The ban on antibiotics triggers the growth of some feed additives such as enzymes and acidifiers. This category is gaining importance and will be applied in feed to make up for the lack of antibiotics and contribute to improved nutrition digestion and growth promotion; and

- Mangaging feed production: This allows feed manufacturers to reduce pollution by harmful micro-organisms. According to Sun and Pan, manufacturers should pay more attention to raw material procurement to ensure quality and supply stability.

In addition to these three aspects, novel products are crucial in animal health. Among antibiotic substitutes, MARA identified probiotics and Chinese medicine as potential candidates for new product research.

Challenges ahead

Though China has achieved remarkable results in reducing antibiotic usage, the road ahead is challenging. According to Professor Thomas Van Boeckel, epidemiologist at ETH Zurich, who works on tracking the world’s antibiotic consumption, data transparency is key. Quoted in Nature, he argued that as the world’s largest consumer of antibiotics, China would do well to take a leading role in systematically monitoring antimicrobial resistance and making data publicly available.

The Chinese livestock sector, too, faces challenges. Rabobank researchers Sun and Pan expect that antibiotic usage on-farm will increase in China, and that disease outbreaks may hit the livestock sector even harder. They state that biosecurity is key: those farms that have no proper biosecurity measures in place will suffer great pressure, and those with better biosecurity and farm management will fare better. Investment in the industry will focus on husbandry practice and on hardware improvement (equipment, housing, software).

Whether China’s plan to reduce antibiotics will be sufficient to tackle the challenges ahead remains to be seen.