T. abortisuis: Is it an underestimated pathogen causing abortions in sows?

When doing unrelated research, scientists in Austria recently stumbled on an abortion in one sow caused by yet relatively unknown bacteria: Trueperella abortisuis. Thanks to ongoing technological development, it was easier than ever to get a glimpse of the unknown. What is T. abortisuis – and why you should know about it?

PIG HEALTH SPECIAL 2024 – read all articles

If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you may never find it. However, with more sophisticated technology these days, increasingly the knowledge grows about swine pathogens that may not be very well-known — or perhaps have gone relatively unnoticed until this moment.

That pretty much sums up the state of affairs for Trueperella abortisuis — not a pathogen that will ring a bell with many. Nevertheless, the bacterium featured in an oral presentation at the most recently held edition of the European Symposium for Porcine Health Management (ESPHM) in Thessaloniki, Greece in 2023. What was this all about?

Around since 1999

First of all, T. abortisuis is not entirely new. Its story started back in 1999, at a 600-head sow farm in Chiba prefecture, Japan, just east of Tokyo. In June and November of that year, the farm reported intermittent abortions in its sows. After pathological and bacteriological examinations, the veterinary team concluded that the fetuses had been having severe lung problems (suppurative bronchopneumonia) and also the placentas had been inflamed (suppurative placentitis). At the time, 3 fetuses were examined, as was the placenta. The team found gram-positive bacteria, strictly thriving in an anaerobic environment, that were either thin or rod-shaped.

Fast forward to 10 years later. In 2009, having done a series of tests on these bacteria, a team of researchers around Ryozo Azuma and Satoshi Murakami of the Tokyo University of Agriculture, concluded that the strain was a member of a novel species. Hence, they proposed the name Arcanobacterium abortisuis. Two years later, this name was changed to Trueperella abortisuis – see box.

Further research over the years

Ever since, additional bits and pieces of information have trickled through about the bacterium. It also was found in sow vaginas, kidneys, cervices, urine as well as in extended boar semen. In addition, the bacterium was detected in other continents. In recent years, for instance the bacterium was reported from the United Kingdom as well as in the US.

Still, as the bacterium’s pathogenic character nor its spread was as obvious as some other swine bugs, most of this happened in relative anonymity. “Nobody really paid any attention to this pathogen, although it was already known and described. I think it has to do with lack of good case reports, as it is indeed difficult to be on time on a farm to collect proper and more or less clean samples.” Says Dr Lukas Schwarz, researcher at the Clinical Department for Farm Animals and Systems Transformation of the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria. He and his colleagues were working on a different research project at the university’s animal facilities when they were unexpectedly confronted with a T. abortisuis infection, in June 2022.

The study in Austria

The bacterium was found in a 3-year-old PRRSv-negative sow in late gestation, Dr Schwarz explained at his oral presentation at ESPHM in 2023. The sow had been transferred to the animal facilities about 4 weeks prior to farrowing, and suffered from anorexia. She did not want to stand up or move. Her vulva was slightly reddened. She seemed reluctant to eat, no matter what type of feed was offered.

One week after arrival, a swab taken from vaginal discharge showed a moderate amount of T. abortisuis even though at this time the fetuses were still alive. Antimicrobial treatment with amoxicillin was started. Her situation, however, did not improve. Abortion occurred 11 days prior to the expected farrowing date. In total, 8 piglets were born dead, and a vet removed another 3 fetuses from the uterus.

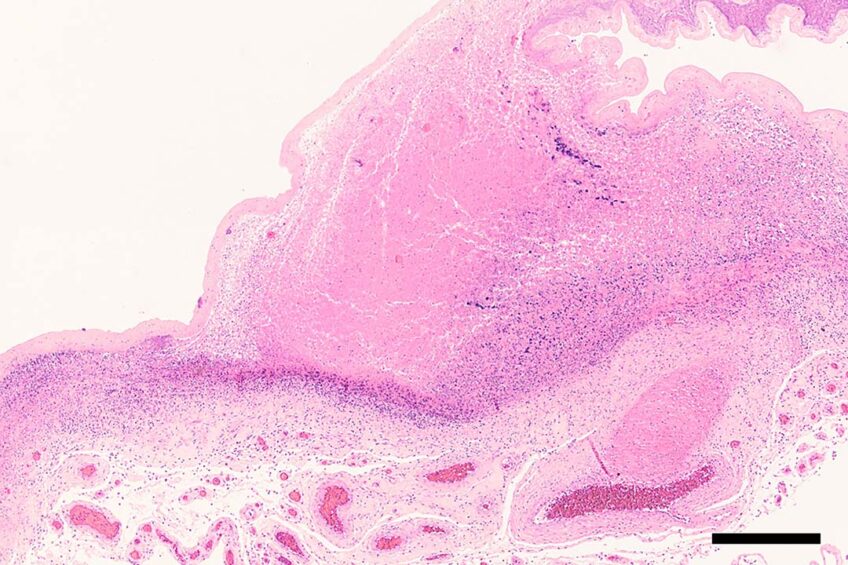

Many samples were taken for examination, for instance, foetal hearts, lungs, kidneys, spleens, umbilical cords, stomachs and placentas. In all fetuses, T. abortisuis was found in one way or another. In addition, in quite a number of cases, the “Japanese” diagnosis showed up in histopathology — i.e. bronchopneumonia and placentitis. The team therefore concluded that T. abortisuis had induced the abortion. One may speculate about the efficacy of amoxicillin treatment. However, Dr Schwarz explained that this most probably has to do with the size of the amoxicillin molecule, which is too large to be transferred via the placenta to the foetuses.

Don’t forget about this bacterium, Dr Schwarz told his audience at ESPHM 2023: “Causes of abortions in sows are sometimes difficult to clarify, especially in case of the involvement of bacterial infectious agents. […] T. abortisuis should be considered an important differential diagnosis causing abortions at least in late gestation in future routine diagnostics.”

Occurrence of the bacteria

In correspondence with Pig Progress, Dr Schwarz emphasises that the occurrence of the bacterium at Vetmeduni wasn’t so much a sign of a growing presence or an increasing pathogenic character, but most likely a matter of chance and coincidence. This allowed them to explore the bacterium in detail. He says, “In our case, this was only possible because the affected sow was in an animal facility already at our university and for use in a different project. The key is the time from abortion to delivery of the samples in the lab, as autolysis and microbial contamination takes place right in the moment after abortion when aborted foetuses become contaminated with environmental microbiota, most probably originating from sow faeces.”

Modern techniques make it possible to more quickly identify rare bacteria, Dr Schwarz adds. In that context he points to the “MALDI-TOF MS” technology — short for “matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation — time of flight mass spectrometry”. This is a novel technique that combines speed, accuracy and sensibility to provide weight information of all kinds of molecular compounds — including those of bacteria.

The near future

Treatment of T. abortisuis shouldn’t be too difficult, says Dr Schwarz, as it is usually sensitive to antimicrobials that also work for its relative T. pyogenes (see box), including beta-lactams such as penicillin or amoxicillin.

So far, immediate follow-up research to the trial is not planned, he says. He adds, “I think once more cases occur, it is worth looking in more detail into which factors may contribute to the abortive mechanism of T. abortisuis and colonisation of the gestating genital tract of sows. T. abortisuis may also be found in vaginal/cervical samples of clinically healthy sows. But I think one key message must be that any case of T. abortisuis abortion has to be reported either by publishing in peer reviewed journals or via third mission publishing. Otherwise this pathogen will stay underestimated for a longer time.”