Post-weaning Colibacillosis: An ongoing problem

Colibacillosis is a recognised major disease and cause of death in the swine industry. Signs of the disease range from reduced appetite, respiratory distress and slow growth. There are still several challenges to overcome in order to improve protection against post-weaning E. coli infections.

PIG HEALTH SPECIAL 2024 – read all articles

In many pig breeding farms pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli are prevalent such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) and/or Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC). ETEC strains produce thermolabile (LT) and or thermostable (STa and/or STb) enterotoxins loss along with fimbriae that allow them to adhere to small intestinal enterocytes leading to gut colonisation and fluid loss with watery diarrhoea as a result. Newborn piglets are particularly susceptible to these infections. Diarrhoea will lead to high mortality if colostrum and milk of sows does not contain sufficient antibodies to neutralise virulence factors of ETEC. The presence of neutralising antibodies depend on prior exposure of the sow to these pathogens on the farm, or on sow vaccination. Various vaccines are on the market to induce colostral and milk antibodies which can neutralise virulence factors of E. coli.

Lactogenic immunity ceases abruptly post-weaning, leaving piglets highly vulnerable to enteropathogens. At the same time changes in gastrointestinal conditions take place with a transition from easily digestible milk proteins to less digestible solid feed, a decreased stomach acidity and a slower intestinal transit. This creates an environment conducive to bacterial proliferation and colonisation, culminating in colibacillary diarrhoea. Colostral antibodies absorbed in the intestine shortly after birth can result in high serum antibody concentration, but serum antibodies do not provide protection against intestinal infections after weaning.

Age and genetics

Not all ETEC can colonise the small intestine post-weaning. Piglets require the expression of specific receptors on their mucosa for successful colonisation by ETEC. This is the case for F4 and F18 fimbriae, but not for F5, F6 and F41 fimbriae. The receptors of these latter fimbriae are transiently expressed the first days after birth. Conversely, F18 receptors (F18R) are absent in newborns and emerge around weaning age. Expression seems to be optimal at the age of 5 to 6 weeks. But not only age determines the expression of receptors, but also genetic factors. As a result, variability in receptor presence can occur between but also within litters on the same farm. Tests have been developed to ascertain receptor absence based on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutations near the receptor gene. The FUT1 test, for instance, distinguishes animals with and without F18R with a very high reliability. In contrast to F18R expression, F4R expression is not age-dependent. Several tests have been developed to differentiate F4R positive from negative pigs, but none of these tests give a 100% certainty.

Pathogenic STEC strains are invariably F18 fimbriae positive and produce Shiga toxin with or without enterotoxins. The Shiga toxin targets many different cell types such as enterocytes, endothelial cells of brain and eyelid vessels and kidney pelvis. Toxin cause protein synthesis inhibition which can lead to apoptosis of cells resulting in oedema with neurological signs and finally death. Symptoms are often seen from the 2nd week after weaning onwards.

Management measures

Weaning induced stress with the removal of piglets from the sow, deprivation of milk antibodies, change in feed and environment and mixing of piglets from different litters fosters ETEC and STEC infections. The use of antibiotics and/or medical levels of zinc oxide (ZnO) to control infections culminated severe antibiotic resistance. Medicinal use of ZnO in piglet diet was banned in the EU in 2022 and strategies have been developed to reduce antibiotic usage. This resulted in an increased prevalence of post-weaning diarrhoea, necessitating alternative strategies to prevent transmission and infection spread. Enhanced hygiene protocols, including meticulous pen sanitation and hand and footwear disinfection, alongside controlled housing conditions and optimised feeding regimens, are crucial. Additionally, environmental factors such as pen size, feed access and temperature can influence PWD prevalence. Colder environmental temperatures, for instance, impede intestinal peristalsis, thereby fostering bacterial colonisation and exacerbating PWD severity, whereas crude protein levels and acidifying agents have demonstrated correlations with reduced PWD prevalence.

Feed supplements

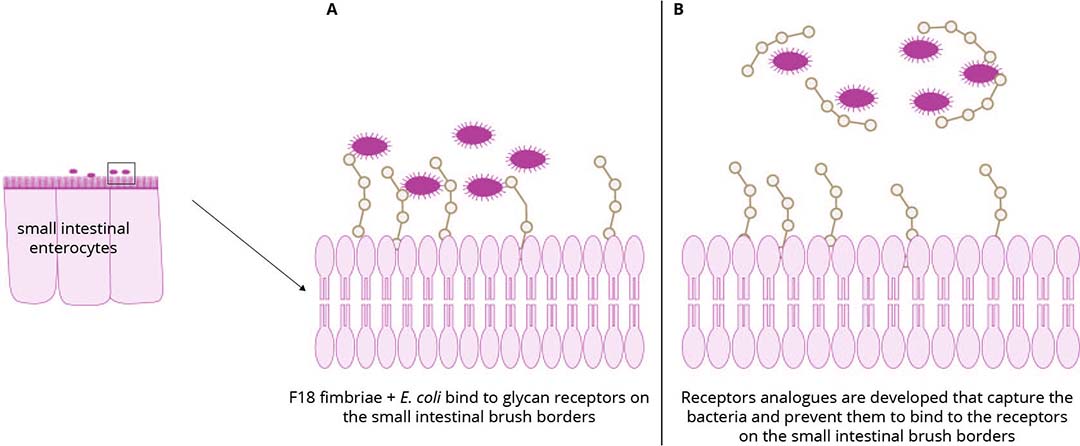

Various dietary supplements have been reported to reduce infection or increase resistance of piglets against infections. For instance, ß 1,3/1,6 glucans enhance innate immunity, cranberry reduces bacterial adhesion to intestinal receptors, organic acids reduce pathogen growth and lactoferrin not only impedes bacterial growth and adhesion but also degrades bacterial flagellin, thereby reducing bacterial motility. A recent innovative strategy, supplementing feed with receptor analogues, has proven successful in both experimental and field trials for F18+ ETEC and STEC infections (Figure 1). These fimbriae bind to blood group sugars on small intestinal epithelial cells. The same blood group sugars can be produced in vitro by bacteria and subsequently conjugated to a carrier. Concentrations of approximately 10 mg/kg feed of this multimeric oligosaccharide effectively prevents clinical signs and significantly improves feed conversion.

Figure 1 – Receptor analogue based inhibition of binding prevents colonisation with F18+E. coli.

Pathogen targeting

Emerging interventions targeting bacteria include bacteriophage cocktails and bacterial antibody fragments against bacterial virulence factors. Bacteriophages, viruses that infect and lyse bacteria, exhibit specificity to particular bacterial serotypes. To address the diverse serotypes of ETEC and STEC on farms, cocktails compromising various bacteriophages should be administered to piglets at weaning. However, a pertinent question that persist is if such broad-spectrum cocktails with effect against most ETEC and STEC can be developed. Other questions to be answered are if scalable production is possible without compromising the quality and efficacy of the phages, if new formulations should be developed for their administration and if bacteria could develop resistance against phages or pigs immune responses that might neutralise their effect?

Another promising approach involves IgA-based antibodies derived from camelid heavy chain-only antibodies (VHH), specifically targeting ETEC or STEC fimbriae. These VHH, grafted onto porcine IgA, demonstrate enhanced stability in the intestinal environment and significantly reduce F4+ETEC infections in challenged pigs. Since bacterial, yeast and plant expression systems have been established to produce them in high quantities at an affordable price, these VHHs represent a potential future therapy.

Vaccination as an ultimate goal

While vaccinating sows results in colostral IgG antibodies, that after been taken up afford piglets protection against systemic infections, and in milk antibodies that protect against intestinal infections during the suckling period, immune protection after weaning has to come from vaccination of piglets.

Intramuscular or subcutaneous vaccinations primarily elicit IgG antibodies, which confer protection against systemic infections. However, these antibodies are not secreted in the gut and thus fail to protect the intestinal mucosa from enteropathogen infection. To safeguard the small intestine, local production and secretion of antibodies resistant enough against the harsh intestinal environment, such as secretory IgA antibodies (SIgA), is needed. Currently, this can only be achieved through oral vaccinations. In general, death or live oral vaccines exist, but for pigs currently only live oral vaccines are on the market. In Europe, the Coliprotec F4/F18 oral live vaccine is offered, containing avirulent strains of F4+ and F18+ E. coli, targeting post-weaning colibacillosis. In the US similar vaccines are marketed such as Entero-vac and Edema-vac, containing avirulent strains of F4+ or avirulent F18+ E. coli, respectively. These live vaccines can be orally administered to pigs from 18 days of age onward, with immunity starting 7 days post-vaccination. It is recommended to discontinue ongoing antibiotic treatment for at least 7 days. Questions regarding efficacy of these vaccines in the presence of neutralising lactogenic immunity and the potential risk on reversion of virulence remain to be answered.

Oral administration of vaccines

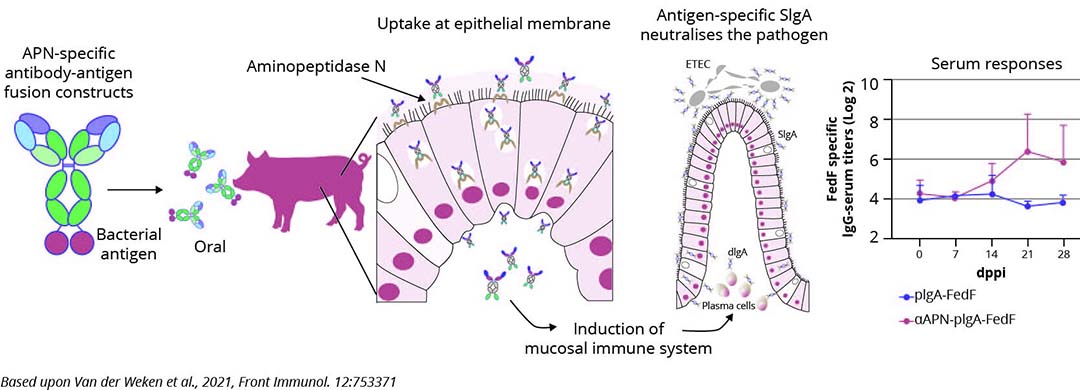

Oral subunit vaccines comprising virulence factors of ETEC and STEC offer potential solutions to some of these questions. At least they exhibit resilience against antibiotic treatment and protective neutralising IgA can be induced by oral administration of F4 fimbriae and of LT enterotoxin. However, as for live vaccines, the presence of milk antibodies may neutralise these subunits before they can induce an immune response. Consequently, vaccination can only occur post-weaning with immune responses typically emerging the 2nd week after weaning. The creation of delivery systems that shield the subunits from neutralisation and ensure their intact release near the gut’s immune system remains an important challenge (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Antibody-mediated targeting of antigens to intestinal aminopeptidase N elicits gut IgA responses in pigs.

Parenteral vaccination

Parenteral vaccination will induce antigen-specific serum IgG. This can be effective in some instances, such as when toxins from gut-colonising pathogens are causing systemic disease, as seen in edema disease STEC infections. IgG antibodies induced by a systemic toxoid vaccine at one week of age can neutralise after weaning the circulating toxin and protect the weaned piglets.

Parenteral vaccination can not only trigger the production of antigen-specific serum IgG but also induces serum IgA, which can be secreted across various mucosae. However, this secretion is transient and reliant on sustained high concentrations of circulating IgA. Crucially these antibodies are not locally produced within the gut mucosa and intestinal infection with ETEC or STEC will not enhance their production. Consequently, piglets will not be protected against infection after weaning. Adjuvants capable of shifting systemic responses towards mucosal immunity could offer a promising avenue and form an interesting future research topic.

There are still several challenges to overcome to improve protection against post-weaning coli infections. From 30 June till 2 July there is an international Symposium in Ghent, Belgium dedicated to Escherichia coli infections and its interaction with the mucosal immune system. ECMIS2024 focuses on innovative intervention strategies. Subscription and abstract submission can be done at www.ecmis2024.be