The importance of implantation (I)

Implantation is an important stage in a successful gestation cycle – and it is a phase that is not to be underestimated. Management expert John Gadd goes to great lengths to explain why in this and two other opinion pieces to follow.

Some producers I talk to are rather hazy about what implantation is and rather more do not give it enough priority on the importance scale. ‘Implantation’ is when the fertilised blastocyst (‘blast’ in scientific terms means ‘a bud’ or ‘budding’ and ‘cyst’ in breeding terms ‘a capsule’) is attached to the nutrient-providing wall of the womb – the endometrium.

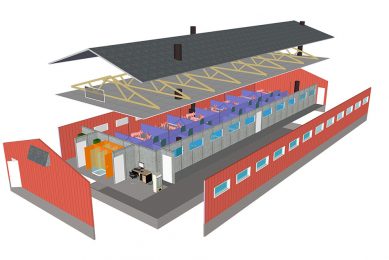

Figure 1 shows where this occurs in the early breeding cycle. Effective achievement results in bigger litters, more even litters as well as heavier and more robust weaners. All these four benefits put efficient implantation right up there in importance.

Figure 1 – Diagrammatic cross section of the sow uterus showing potential sites for improving reproductive efficiency.

Litter even-ness is slipping now, partly due to the larger litters we are achieving these days, which is mainly due to genetics, along with better care and stockmanship of course. With much larger litters there are bound to be more lighter weight tail-enders in the queue waiting to be expelled, thus in the present larger-litter scenario, implantation and what affects it is ever more important.

Understanding of implantation needs an update

Talking to producers I find that their understanding of implantation needs an update. They know it is important and that management is vital for the month after service, but need instruction on why. Understanding the ‘mechanics’ of implantation (not the right word, but you know what I mean) and especially what interferes with it and which follows from it, will provide more pigs born alive, more even birthweights, stronger weaners and fewer post-weaning troubles.

This latter is very topical now that high level post-weaning zinc oxide is to be phased out. So what happens in those vital few days post-service when the fertilised egg turns into a blastocyst – the forerunner of the much later embryo? Don’t turn the page – keep reading, it is important for you, as when implantation management is correct, the beneficial results apply (Table 1).

All compiled from clients who have understood what happens and acted on it, for almost no extra cost.

How the sow manages things after service

After successful service the endometrial surface starts to regenerate from what I call the ‘suckling state’ to the ‘receptivity state’, triggered by the cessation of suckling. Whilst the suckling reflex is present, the female protects herself from having to form another litter while she is still raising the present one by keeping the endometrial surface hostile (again my word for it) to any blastocyst which arrives – in these circumstances, unwanted.

When suckling ceases, nature, through her altered balance of hormones, informs the sow that things are ‘receptive’ again and it is ‘systems go’ for the next litter.

An extraordinary phenomenon

About 12 days from service/fertilisation the blastocyst changes remarkably into a nucleus with two thin and wavy extending arms, each up to 100 times longer than the original blastocyst, and which is termed the ‘filamentous stage’, which enables the organism to attach and then embed itself into the nutrient source. But it needs to secure sufficient space to do so – within the next ten to 14 days. So the first findings suggested that enough receptive space on the womb wall for this to happen is vital, see again Figure 1.

The most important to my mind is freedom from stress in the two to three week implantation period. I suggested a phrase for it 40 years ago ‘the feel good factor’, which is the subject of my next two articles. Farmers who secure the feel good factor throughout implantation can reap the benefits of Table 1.