Slow growth boosts gilt longevity and productivity

Sometimes being a diesel is not such a bad idea – for reproductive sows that certainly holds true. Recent research has been showing that it is better for gilts to take their time in developing. Later in life, they will prove to be more robust, leading to better longevity.

The opportunities to improve sow longevity remain significant, as illustrated by the words of Dr Ken Stalder, internationally recognised researcher in applied swine breeding and genetics at Iowa State University: “Sow longevity is a key productivity indicator trait that has real economic and welfare importance for commercial swine farms globally.”

Genetic evolutions have continued to prioritise improvements in litter size and growth rates in recent decades, along with improving lean compositional traits and feed efficiency. However, this has contributed in part to fewer average number of years in the herd for modern, prolific females. An excessive number of young sows are culled for reproductive failure or feet and leg problems, driving renewed interest in understanding genetic, nutritional, gilt development and other factors that influence sow longevity.

Healthy body condition

Sustaining healthy body condition throughout all reproductive phases is key to maximising sow productivity and longevity. Reproductive health, performance and welfare are compromised when gilts or sows become either under-conditioned or over-conditioned. Less is known about the importance of growth rate, development, feeding and management factors for growing gilts intended for breeding.

In 1999, Professor Dale W. Rozeboom of Michigan State University suggested that the longevity of genotypes with “average lean” could be improved by limiting energy intake during development. Restricting energy to slow growth during development can reduce the likelihood of feet and leg disorders. However, underfeeding protein during gilt development can reduce oestrous expression and delay puberty. Overfeeding protein to developing gilts is expensive and may decrease longevity.

Moderate protein, high-energy diet

Genotypes characterised as “very lean” often receive a moderate protein, high-energy diet offered ad libitum during their development, particularly in North America. The recommendation that very lean genotypes be fed high-energy diets with moderate protein is based on the expectation of lower voluntary feed intakes and the risk of becoming too lean, increasing the likelihood of culling for reproductive failure at a young age.

Additionally, mammary development before puberty may be enhanced by ad lib feeding after 90 days of age. However, many current genetic lines have exceptional growth rates when fed ad lib, which can result in a greater risk of becoming too heavy at breeding and reduced longevity.

In general, too many young sows are culled from breeding herds. The primary reasons are reproductive disorders or failures and feet or leg problems, associated with fast-growing or over-conditioned gilts. Despite identified risks associated with reducing gilt growth by limit-feeding (i.e. delayed puberty), some existing research has shown that slowing growth with restricted feeding after ten weeks of age may reduce the incidence of osteochondrosis (OCD) or improve bone mineral density and locomotion scores, and perhaps improve longevity. Dietary restriction before ten weeks of age followed by ad lib feeding, however, may result in greater risk for OCD. Nevertheless, restricted feeding programmes are difficult to implement and impractical for most farms, especially when gilts are housed in groups. More research is needed to develop practical diets and feeding programmes that moderate the growth of developing gilts so their welfare and lifetime reproductive success may be improved.

Recent research (2023) from the University of Arkansas, JBS Live Pork, Genus PIC and DSM–Firmenich is shedding new light on the potential to improve sow longevity by slowing gilt growth during development (see Table 1).

Treatments

Treatments were fed ad lib until breeding. Dietary nutrient density treatments were withdrawn upon breeding. Females received the same gestation and lactation diets except that they remained on their respective vitamin D treatments through four reproductive cycles or until removal for culling or mortality reasons. Groups of 12 replacement gilts were routinely received and handled the same as the initial groups of gilts so that the three original groups could be sustained through four cycles.

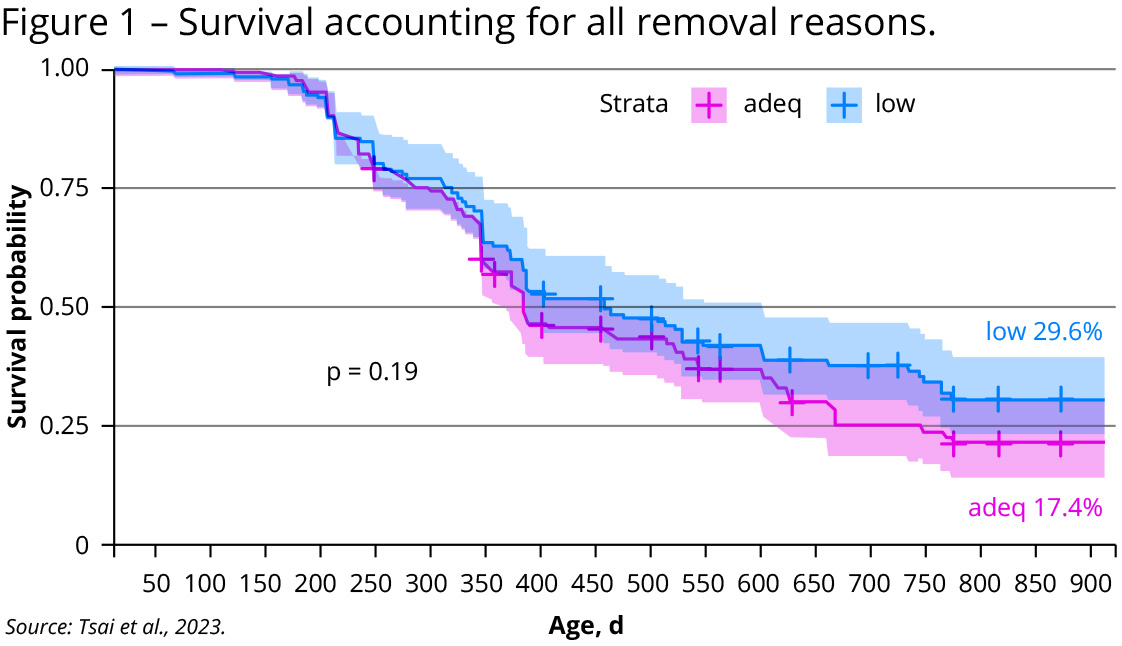

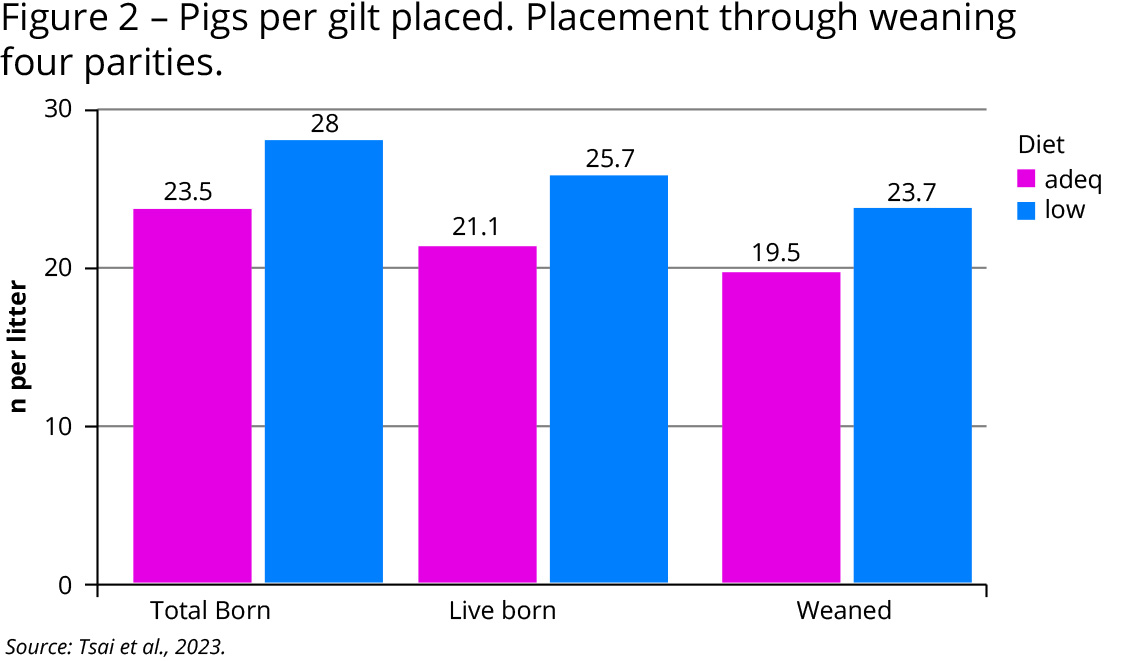

As anticipated, gilts fed the “low” diets had greater average daily feed intake but reduced average daily gain and were less efficient during their development. Consequently, gilts fed “low” diets had reduced body weight (149.8 kg vs. 153.9 kg) and backfat depth (20.3 mm vs. 22.3 mm) at breeding. There were no differences in the growth performance of gilts fed the two vitamin D treatments during the development period. Although there were no significant differences between any of the treatments for overall reproductive performance on a per litter farrowed basis, the retention of gilts beginning at nine weeks of age until the completion of four reproductive cycles was greater (29.6% vs. 17.4%; see Figure 1) for those fed the “low” diets before breeding. That difference resulted in 4.2 more pigs weaned per gilt at nine weeks of age (see Figure 2).

Reproductive reasons were the primary causes for removals. Only nine females were removed for poor structure across treatments. Finally, post-weaning growth performance of progeny from one farrowing group was monitored, and pigs from gilts/sows fed 25-OH-D3 averaged 3 kg heavier at 168 days of age.

Slowing gilt growth can improve lifetime reproduction, and progeny performance can be improved by good sow nutrition, in particular optimised vitamin D3 nutrition.