How pigs perceive smells – tapping into new potential

This article is part of our Premium content.

Join our Premium community if you want to have access to all our content.

Subscribe here.

It is no secret that pigs have a good sense of smell. But do they smell everything – and how do the smells affect their behaviour? Researchers in Sweden aim to unravel those questions and learn more about what makes pigs tick in terms of olfactory challenges.

That pigs can search for and find truffles using their nose is well-known, and even children’s books mention pigs’ great sense of smell. When it comes to science, there is quite extensive knowledge on the olfaction of rodents; they are often used as a model for the human sense of smell. But when it comes to the olfactory abilities of farm animals, knowledge is sparse.

In a project funded by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (known as Formas), a team of researchers investigated pigs’ olfactory abilities, their reactions to odours, and the potential of using odours to enrich the lives of pigs.

Holes in a pen wall

In the first part of the project, the team enlisted 192 growing pigs at the SLU Lövsta research centre in Uppsala, Sweden. Pairs of pigs were kept in pens with 2 holes placed in their pen wall. One hole emitted 1 of the 12 experimentally included odours, while the other hole contained an odourless control.

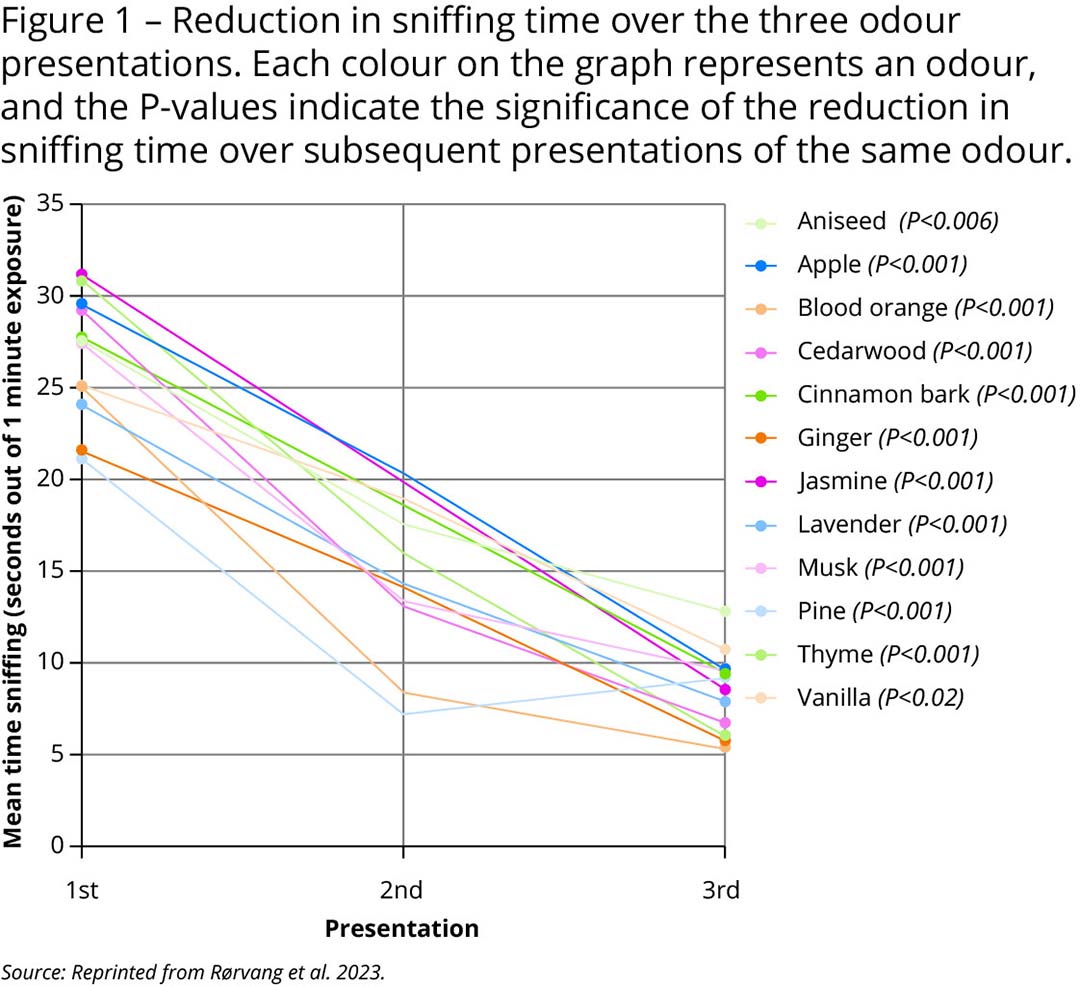

The researchers recorded how often and for how long the pigs sniffed at each hole. The same odour was presented to the pigs 3 times in a row (each time for 1 minute). Each time the odour was presented, the sniffing time decreased. However, when a new odour was subsequently presented, the sniffing time went up, indicating that the pigs recognised it as a new odour. In other words, they were able to detect and differentiate between the different odours.

Strong interest in odours

Sniffing, together with other behaviours shown by the pig, indicated a strong interest in the odours. The pigs were tested in pairs, but each hole only had space for 1 pig to sniff at a time. Some pigs would push or bite their pen mate to retain access, and the team observed significantly more of this aggressive behaviour at the odour hole than at the control hole. That indicates that pigs find odours interesting and may perceive them as a resource.

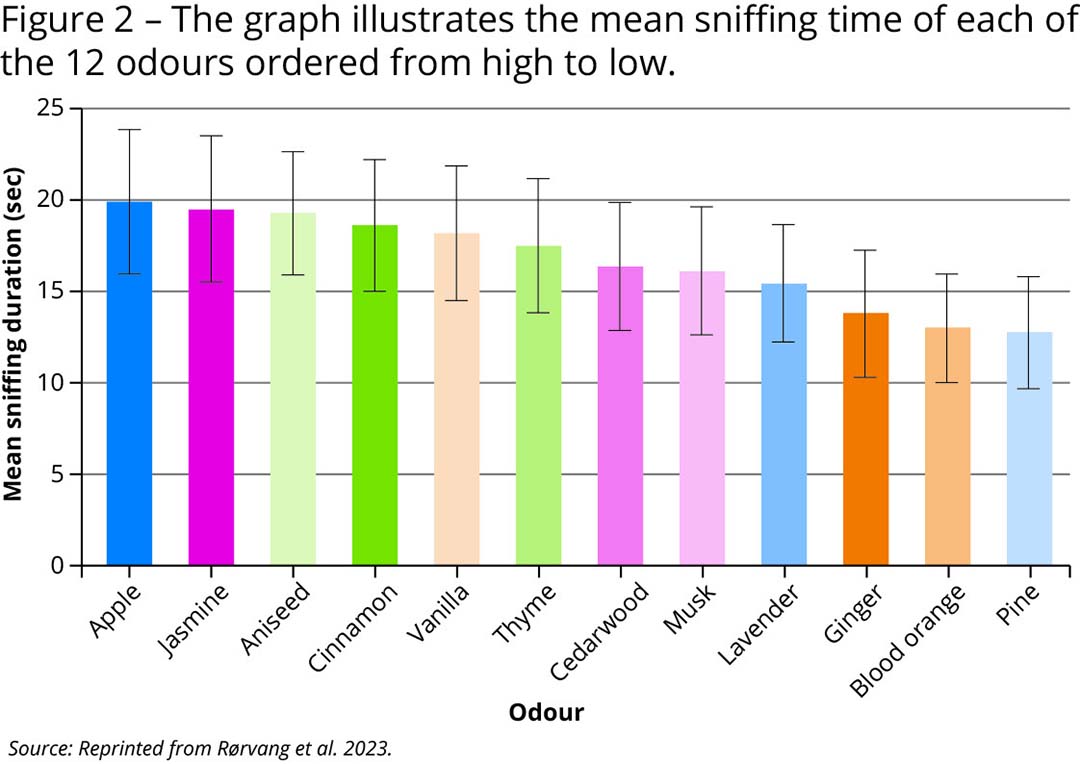

As the experiment was not designed to investigate odour preference, the different odours were not tested against each other. However, looking at the total sniffing time per odour, pigs spent the most time sniffing apple and jasmine, while the least amount of time was spent sniffing pine and blood orange.

The researchers also observed that most pigs showed signs of a motivation to “eat” or taste the odours; they expressed biting and licking behaviour around the odour hole despite not being able to access the odour source. Jasmine odour elicited a lot of this feeding-like behaviour. Moreover, the pigs were eager to rub their faces, necks and entire bodies against the odour hole.

Rubbing and rolling behaviour

Sometimes the pigs even started rolling after sniffing the odour, similar to the rolling behaviour often described in companion dogs. All 12 odours elicited rubbing behaviour in the pigs, but vanilla elicited the least rubbing. Rubbing and rolling behaviour as a response to an odour has not previously been described in pigs, and these behavioural reactions therefore warrant further investigation.

Although most researchers are familiar with rubbing and rolling behaviour in predators, such as dogs, cats, and lions, it is currently unknown why they perform the behaviour. There are, however, a variety of theories; in social animals, it is argued that the animals may be motivated to apply an odour to become more attractive to potential mates or to increase their social status. In apes, there are even studies showing that they use odours in the same way as humans, as perfume. For predators, it could be a way to camouflage their scent for hunting. And conversely, for prey animals, it could be a way to mask their scent from predators.

In addition, for pigs, it could be a way to protect themselves against insects, skin infections, or parasites. But it could also be a sign of excitement, play or comfort behaviour.

Using odour enrichment

The next step in the project is to determine if odour enrichment could be used in commercial pig production. Experiments are currently underway in a conventional Swedish herd. In that experiment, the team selected the 5 most promising odours. They are sprayed onto the straw that the pigs normally receive as enrichment material, and the team have hopes to discover whether or not adding odour can increase the enriching value of the straw.

Questions to be answered are if pigs spend more time engaged with odourised straw than normal straw, and if so, does their welfare improve as a result? In this experiment, the behaviour of the pigs is being monitored in the same way as in the first study, but additional recordings of welfare scores of the pigs are collected during the entire fattening period. The project runs until 2024, and the researchers hope to have the opportunity to further expand the research after the project has ended, including studies of the production economics behind odour enrichment, as well as odour enrichment for other groups within pig production such as breeding sows.

Other contributors to this project are Sarah-Lina Aagaard Schild, Johanna Stenfelt, Rebecca Grut, Moses A. Gadri, Anna Valros, Birte L. Nielsen and Anna Wallenbeck.