Redefining body condition scoring for gilts and sows

To maintain health and reproductive performance on pig farms, body condition monitoring must evolve to be more accurate and actionable. A new digital platform, based on ultrasound data from back fat and loin muscle depth, is redefining this practice.

Today’s highly prolific sows have been genetically bred to produce large litters that have fast and lean meat growth. This has also changed sows’ metabolisms and nutritional needs. Piglets grow exponentially in the last ten days before farrowing. To support this growth spike (of a large litter), as well as facilitate proper development of her own mammary glands for lactation, the sow needs extra energy and amino acids.

If the diet in this stage does not meet the sow’s nutritional demands, fat and muscle tissues start to break down. Also, mobilisation of these body reserves throughout the gestation period can negatively affect sow productivity and leads to compromised performance of the litter, reflected in less vital piglets or an increase in the number of stillbirths. In addition, it can lead to reduction of feed intake of the (lactating) sow, which can create further spiralling problems for sows and piglets.

Redefining body condition scoring method

Health and optimal body condition are key for sows to reach their genetic potential. Body condition scoring is a manual method of estimating back fat on a scale of 1 to 5. Farmers and feed advisers have been applying this method for many years. However, visual confirmation of the gilt’s and sow’s body condition is subjective. Scales, measuring tapes and callipers can be used, but they lack accuracy and provide limited information on the different tissues reserves. Since modern sow genotypes are characterised by intense muscular lean growth, solely relying on back fat measurements is not sufficient to evaluate the metabolic condition of sows and gilts. Measurements of the back fat layer and of loin muscle depth provide more accurate insight into important metabolic reserves, such as lipid and protein mass.

To obtain the most accurate data on the body condition and its evolution, it is important to measure both back fat and loin muscle depth at regular intervals during the sow’s reproductive cycle. Measurements can be carried out at the following moments: at days 35 and 85 of gestation, when animals enter the farrowing house (at day 110), and at weaning.

Recent sow trial results

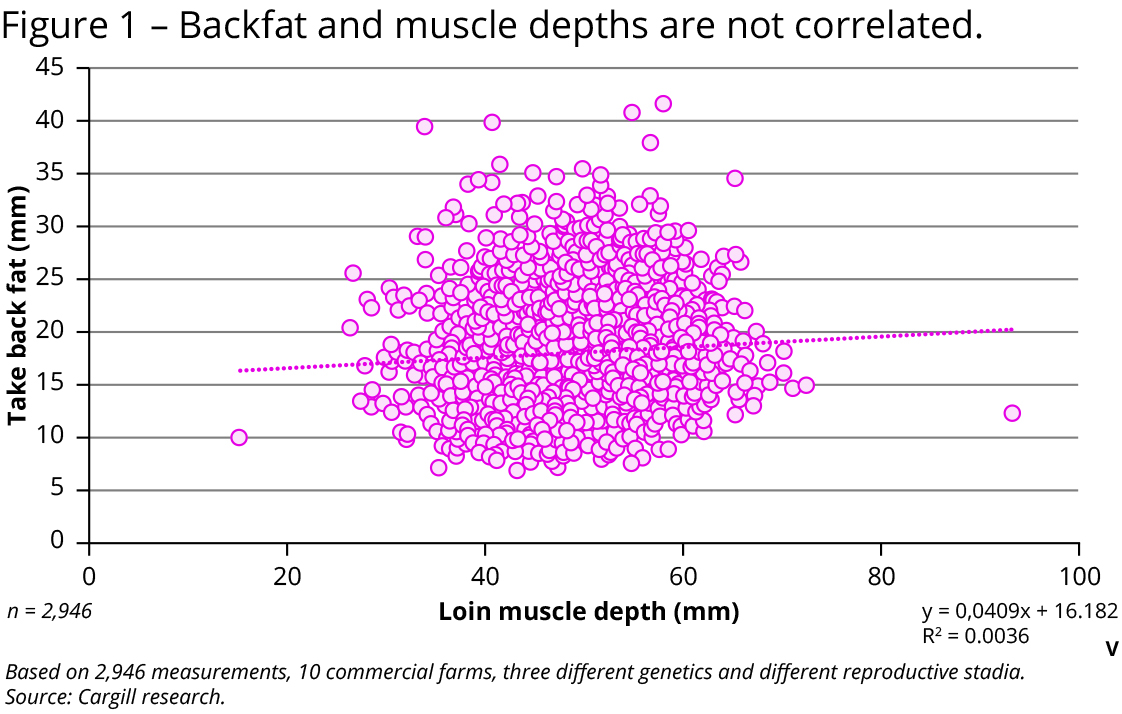

Animal nutrition company Cargill has conducted many research studies over the last few years based on thousands of measurements and different genetics. These trials highlight the importance of routine and accurate monitoring of sow and gilt body condition, specifically the back fat and loin muscle depth. It was for example shown that while back fat and loin muscle depth are not correlated (Figure 1), there is an optimal ratio between the two that needs to be considered when working towards optimal body condition. This optimal ratio is, however, complex and different for different stages, parities and genetic breeds of sows.

Trial results on commercial pig units (2022) showed that gilts have a higher protein requirement to support further growth. The gilts with a lower back fat to loin muscle depth ratio at first insemination were less productive, suggesting that optimal back fat and muscle depth at first insemination is important to ensure their optimal productivity. The data also showed that muscle mobilisation during gestation was more pronounced in highly productive gilts. This excessive muscle breakdown in the last weeks of gestation was negatively linked with piglet survival. Multiparous sows show the same trend. So, while in high productive sows muscle mobilisation is unavoidable to a certain extent, it should be limited to avoid an increase in stillbirths.

Trials in Belgium in 2020 also highlighted the impact of sow body condition during lactation on litter performance. A positive linear correlation was seen between sow back fat loss in lactation and litter weight gain, suggesting that sows mobilise body reserves to support milk production.

The study also indicated that the large amount of loin muscle mobilisation in lactation has a negative impact on litter size in the next cycle, which was also reported in a 2020 study in the Netherlands by a team around Natasja Costermans, attached to Wageningen University and Topigs Norsvin.

Digitalisation of ultrasound data

Because back fat and loin muscle depth combined give a more complete picture, it helps to better formulate feeding programmes to ensure gilt and sow nutritional requirements are met while maintaining optimal body condition. A great way to measure this is using ultrasound. Most people are familiar with this technique, which is used for example to visualise a foetus during a prenatal examination. It can also be used to measure fat (three layers of backfat at the last rib curve) and the muscle depth in pigs.

With long-standing expertise in animal nutrition and digitalisation, the company therefore looked for a way to track the metrics from the ultrasound and harness the data in a digital and easy way. That specially developed software service stores the data from the ultrasound scans and can benchmark the data collected from multiple recorded units. Monitoring throughout the reproductive cycle empowers farmers to identify areas for improvement and make the changes needed (e.g. add another silo for multiphase feeding). Technical support staff have more insights into the dynamic evolution over time and can advise accordingly.

More accurate feed formulation

Having accurate data stored in one digital place helps nutritionists to formulate more to the animal’s needs, as can be done with Cargill’s two-phased gestation diet.

Phase 1 is fed up to around day 80 and will support the sow’s body recovery. The lysine and energy contents of this diet will depend on the sow’s phenotype (standard or lean sow) and on the specific goal such as backfat, backfat and weight or weight recovery. Consequently, there are several diets that can be applied with different energy and amino acid ratios.

Phase 2 is fed from around day 80 and includes a high lysine to energy ratio to avoid muscle breakdown. This diet also has a specific amino acid profile to take account of the higher lean meat content of the lean genotype sows, as well as the needs for foetal and udder development. Applying this practice to a 600 DanBred sow farm recently showed that monitoring total back fat and loin muscle depth helped when adjusting diets. For example, the gilt rearing feeding programme was adjusted to a lower amino acid : energy ratio, and, in gestation, the second phase gestation feed was implemented one week earlier. Those feed adjustments led to more optimal body condition and improved herd productivity, which resulted in a profit of € 10 more per sow per year.

Conclusion

Recent research and improved knowledge of backfat and loin muscle evolution in gilts and sows highlights the need to monitor accurate body condition. Manual body condition scoring is not providing the information needed to adjust diets and manage long-term productivity in breeding herds. Improved body condition monitoring with the use of ultrasound techniques and digital services to manage and benchmark the data opens the door to more precise rationing on an individual unit basis.