Optimising production efficiency is key

There can be no doubt: future generations will have to take care of more livestock and pigs than has hitherto been the case. In order to feed future generations and in order to get the full potential from all these animals in a sustainable way, it is necessary to answer that one vital question: how? Professor Leo den Hartog, Wageningen University and Research Centre, shares his ideas.

By Vincent ter Beek

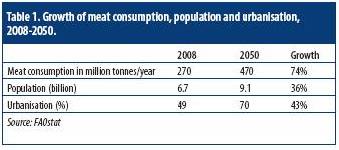

To understand better the feeding challenges the world is facing, let’s start with some figures. Several long-term projections envisage that in 2050, the world population will have risen immensely compared to these days, see Table 1. According to the FAOstat, the globe will be inhabited by 9.1 billion people, a 36% growth in comparison to the world population as it is estimated nowadays.

On top of that, many of these ‘new’ people will have more money to spend – hence demand for food proteins will rise drastically. Hence, there can be no escape: the number of farm animals, including pigs, will have to rise considerably until that time.

“There has to be an expansion, in some continents a stronger one than in others. Half of the world’s population will soon be in Asia, so the biggest demand for pork will come from there.” This says Prof Dr Ir Leo den Hartog, director R&D and Quality Affairs at animal nutrition company Nutreco, the Netherlands and a lecturer attached to Wageningen University and Research Centre.

In June 2009, the animal nutrition company hosted its biennial agricultural symposium Agri Vision, this year completely dedicated to the question how to feed the world in 2050. Den Hartog contributed to the symposium with a comprehensive presentation as to how to get there as agriculture: through ‘sustainable precision livestock farming’.

“In some parts of the world, there is over-consumption, for instance in Northern America, and also in some parts of Europe. Maybe one should move to a different kind of behaviour over there. But it is clear that the demand for animal proteins will grow, predominantly in third world countries. Therefore, we will have to produce more efficiently within the existing system, by monitoring and knowledge and at the same time emit less. But we will have to be realistic: the number of animals will have to grow to meet future global demands.”

Resources

Having more animals will put a reasonable pressure on planet Earth’s resources, hence there is a challenge for agriculture to step up its efficiency, Den Hartog says. “Considering pigs, poultry or cattle, we can say that a large chunk of productivity is not used at the moment. I’d say about 30-40% of genetical capacity.

This can be due to suboptimal health, subclinical disease, etc – hence an integrated approach of agriculture is the way ahead. Only investing in additives or good feed is simply not enough when e.g. the climate is not perfect. Dealing with restrictions in agriculture requires an integrated approach.”

Den Hartog is keen to add that this 30-40% not only exists in developing agricultural markets. “Even within Western countries one can tell the difference, as large differences can exist between farms.” “In the Netherlands, a trial researching faeces samples of individual pigs at 14 farms showed that the digestibility in feed proved to be different – with differences up to 10%. All farms used the same feed, but management, housing, hygiene were different. The moral of the story is that, even when all ingredients are perfect, an optimal result is not guaranteed.”

“Another trial in the Netherlands included purchasing ten pigs from ten different farms, house them individually and see how they performed during finishing. In practice they could grow 700-800 grammes/day, but in our trial they reached 1 kg/day. Hence, in experimental circumstances, individually housed, plenty of space, commercial feed, the enhanced genetic capacity proved to be there – even in Westernised countries.”

“Situated between the food industry and animal resources are animal feed and farm management – and this is where sustainably optimising productivity is key. Efficiency in this sense has two advantages: producing more and emitting less.”

Knowledge is power, hence full system control is essential at farms. “In feed milling, one can see full system control is already happening,” Den Hartog says. “It is vital to monitor developments in an early stage so applying changes is possible, for correcting or preventing purposes. And it is important that ingredients and products are available at the right moments. “Pigs produce more and more with more piglets per sow per year, a higher growth percentage – hence the application of right ingredients becomes even more vital as well.”

Concentration

How to improve this, however, is a discussion that requires much further thought. Some ideas can be found in Figure 1. Especially in densely populated areas, suggestions have been made as to concentrating the number of animals in large places designed to have farrowing, growing, finishing and slaughter efficiently at a short distance of each other.

“Densely populated pig production sites in one place, however, also bring heavy risks,” Den Hartog recalls. “In the US production sites include 100,000 pigs – but should there also be farms of 1,000,000 pigs? Risks will be enormous. It is true that once investments happen on a too small scale, investments in sustainability are also less likely to happen.

For instance in China, approximately 70% can be found in backyards with 1-15 pigs. Building new facilities for 2,000 or 20,000 pigs could lead to investing in efficiency, welfare, environment or manure processing. Just remember there is a limit to these increases.”

Tendencies

Farms of the future will greatly depend on the line of thought in future decades. Insights will continue to change, he says, and so will ‘ideal’ future farms. “In case general standards of living increase, there will be an increased amount of attention for the way the animals are being kept.

In North Western Europe, this discussion is currently going on and will continue to do so. Questions related to how animals are kept, linked to housing and feeding concepts? And are they individually housed? Or group housed? Should the piglets be castrated or not? All these discussions will have their effects on e.g. feed conversion and hence feeding practices need to be adapted. “Similarly, in Asia, in addition, food safety has become a very important issue, which could be seen in the melamine scandal in China.

“Thirdly, the environment is also playing an important role, not only in Europe, but also in Asia. Even in China there’s an increasing amount of awareness, people saying: our children have to live as well. And supermarkets in North Western Europe have started adding ‘carbon footprints’ to certain amounts of products. Increasing farm size has consequences for the environment. So how can we use feed additives that will cause less emission, less phospohrus, nitrogen, methane or carbondioxide, less greenhouse gases?”

Livestock & carbon footprint

This last point has been receiving more and more attention over the last couple of years. Despite an apparent large influence on greenhouse gases of livestock production, there can be no doubt that livestock in general and pigs in particular are vital for future generations, Den Hartog knows.

“Beef cattle, measured in greenhouse emissions, emits the most per kilogramme protein. Fish and poultry emit the least and pigs are in between. It is said that poultry consumption will rise the strongest in the future, as poultry is being eaten all over the world – beef and pork is not eaten everywhere for religious reasons.

“Still: at a recent conference I have suggested the following statement: intensive livestock farming cannot be missed in the food industry, now and in the future. Especially for cattle, as in this world there are vast amounts of places where nothing else but grassland can be cultivated, which needs to be transferred into milk and meat.

“One of the advantages of pigs is that it can be fed many more co-products as the animal is omnivorous.

“In some countries pigs can literally be present in kitchens, eating all leftovers. But for instance in the Netherlands, enormous amounts of co-products of the liquid food industry flow to pigs – amounting to millions of tonnes. They add value to co-products from whey, potato skins and wheat concentrates from the food industry. In case there was no animal feed industry, this had to be dried and/or burnt, which would cost a lot of energy and yield a lot of emission. In that sense, the animal industry is important to direct co-products into high-value products.”

Pig Production in ten years from now Every year, several research organisations publish their projections for the next decade. Not surprisingly, optimistic projections as published in 2008 had been replaced by slightly more moderate expectations – at least in the short term. After 2011, the pig and pork market is expected to once more grow, supplying food for the increasing world population. The Fapri 2009 US and World Agriculture Outlook, compiled by scientists from Iowa State University and the University of Missouri-Columbia and published in January 2009, does mention the crisis’ effects, but anticipates these which will not be long-lasting. “Recent market turbulence originating in the advanced economies spreads and slows down world economic expansion in 2009 at a rate of -0.7% world gross domestic product (GDP) growth. However, significant recovery is projected the following year, with a long-term real GDP growth rate of 3.5% reached by 2011. After recovery, the emerging markets of China and India still post solid growth, averaging 8.6% and 7.5% per year, respectively.” Using these assumptions, positive long-term outlooks for pig production can be noted. “Though some decline is expected in 2009, the long-term trend of increasing exports is expected to resume in 2010. The combination of a smaller Canadian hog herd and uncertainty over COOL implementation will result in fewer hogs entering the US from Canada,” the Fapri outlook notes, expecting a maximum contraction of the US sow herd by 250,000, after which numbers grow again until 2015. Similar key assumptions related to the crisis can be found in other projections to 2018. The report USDA Agricultural Projections to 2018 foresees in its outlook (February 2009) slightly declining pig numbers until about 2012, after which numbers are growing again. “Pork production declines in 2009-11 in response to high feed prices and then grows for the remainder of the projections as higher hog prices improve returns. Production coordination and market integration between the United States and Canada continue in the hog sector. Canada is the major supplier of live swine imported by the United States.” The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2009-2018 notes a similar trend of initial contraction and stability, but expects worldwide growth after 2011. The pig meat sector will continue to grow, with projected consumption and production increasing from 102 million tonnes (2009) to 120 million (2018), with an average growth rate of 1.8%. Prices per kg dead weight are projected to be €1.36 in Europe and US$1.63 in the United States. Total meat consumption goes up to 68.7 kg/year by 2018, from 66.6 kg on average between 2006-2008. China, Brazil and Russia continue to dominate the pork trade scene, the EU’s DG-Agri Agricultural Commodities Markets Outlook 2009-2018 comments. “The increase in world pork consumption and production over the projection period is again expected to be mainly led by China and other important emerging markets such as Brazil and Russia; however, the sector is supposed to grow, although at a lower pace, also in the EU and in the USA.” The financial crisis, the H1N1 outbreak and pork trade developments are conveniently summarised in one paragraph, saying: “In 2009, world pork trade is expected to return to a more habitual level after the record registered in 2008. The recovery of Chinese production will probably put an end to the exceptional export opportunities on the world’s largest pork market. Besides, the effect of the economic crisis, the recovery of beef exports, as well as the trade restrictions adopted by some countries to counter the scare linked to the outbreak of the swine flu H1N1, will further hamper the development of trade in 2009.” Despite projections of Canada’s and EU’s exports to decline, DG-Agri adds: “Nevertheless, world trade of pig meat is likely to expand at a moderate rate (+1.8% per year) between 2009 and 2018. Total exports are thus projected to reach 7.1 million tonnes by 2018, which is a slightly higher level than the record year 2008.” |

Source: Pig Progress Volume 25 nr 9