Lifelong freedom of movement for breeding sows

If there were no limitations, if everything was possible, what would pig farms look like? Here, freedom of thinking led to freedom of movement. What will a breeding farm look like if freedom of movement became essential? Big Dutchman embarked on a quest to find out.

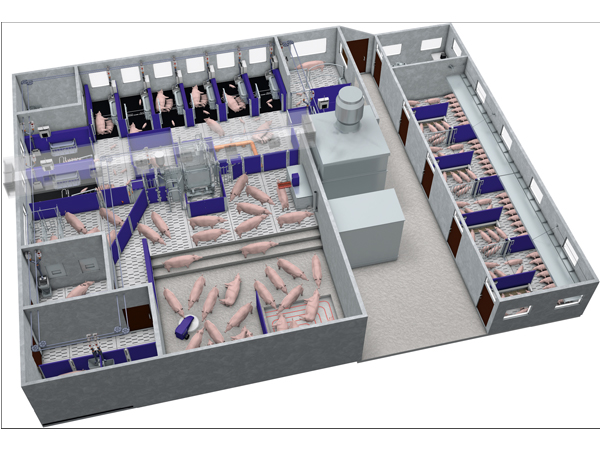

Without any doubt, one of the highlights of the recent EuroTier, in Hanover, Germany, was a thought-provoking model of a concept pig breeding farm. Livestock equipment company Big Dutchman was responsible for this booth-size farm model, filled with a total of 40 plastic sows and 80 plastic piglets. The model showed what swine production may look like in 17 years from now – not surprisingly a number of the company’s innovations were showcased inside.

The concept study as shown at EuroTier was not just a stand-alone crowd drawer, neither was it a case of cunning tactics to draw more attention to the company’s product range. It was a spin-off of a longer-term project by Big Dutchman in order to find out how to be prepared for challenges of the future, explains Daniel Holling, product manager of sow feeding systems and responsible for the concept study, called ‘Pig Production 2030’. He explains, “In essence, this is a welfare farm. The basic idea is to provide free movement for sows during their entire lifetime.”

With this idea, the company clearly anticipates future legislation. As from 2013, all sows have to be kept in groups in gestation in the European Union – and more is likely to follow. Holling says, “We have to say thank you to Mr Mannebeck for having designed one of the first Electronic Sow Feeding equipment as this made the industry have solutions ready once the 2013 was finally upon us. One of the next things is going to be the farrowing area, where sows will get more possibilities to stretch their legs. We cannot afford not having ideas about it. We would like to be ready for these big changes due to requests from future laws.” In short – setting new targets for complete sow freedom – preferably in such a way that farms can continue to make money. Now that is quite a target. For Big Dutchman, it meant the development of a new farm model.

Model set-up

Restriction is something the sows in this model will rarely see. Only three days per cycle: One day for insemination and two around farrowing – during all the other days, the animals can move around freely. Even in the early days of lactation, seclusion is only relative, Holling says, as sows cannot leave their pens, but are free to move around inside as there is no crate containing their movement. Sows living in freedom, in the set-up of Big Dutchman, this all happens in one room. The main idea behind this is that both gestating and lactating sows can use the same Electronic Sow Feeding (ESF) unit, located in the middle of the building. The transponder in their ears will always guide them back to the area where they belong after the feeding session. For the gestation area, the set-up looks reasonably familiar, with ESF and group housing. Holling points to some welfare elements that can be added, like e.g. a toy feed dispenser, as well as a rolling brush that can roll over their backs.

Once sows are being moved to the lactation area, behind the low wall, an entirely new world opens up for them. The set-up shows ten pens of 2.20 m length and 1.80 m depth. As said, this is where the sows will have to stay for the first two days after farrowing – after that the regime for her is loosened. In the concept plan, the top part of the door can be taken off, so sows can enter and exit the pen by stepping over a 30 cm threshold without the piglets escaping. After about eight days, when the piglets are old and strong enough, a little flap is opened and they will have their own door to run around and communicate with the piglets from other pens.

From a hygiene perspective, the concept may differ somewhat from some other schools of thought where piglets of different litters ought to be separated as much as possible, to avoid cross-contamination. Holling explains: “All litters have their own microbial climate – think about flu, sickness or immunity. In conventional piglet production, the nursery is the place where all meet. We just take it one step earlier, we try to see if early immunity benefits the piglets.”

Further study will be conducted as veterinary research teams from several universities will zoom in on this theme. Holling says, “Complete analyses will be made on PhD levels. We will be provided with full microbial and immunological statistics.” Ethological as well as reproductive and economical aspects will also be studied. In theory, piglet production benefits in one other way, Holling says, as it is expected that piglets benefit from the fact of there being more milk available due to cross-sucking. “The big aim is to have all piglets reach an even size. The more milk there is available during lactation, the better this will work in later phases of pig production.” In the EuroTier set-up, not surprisingly, the farm model did include several Big Dutchman innovations, like the SonoCheck and SowCheck, automatic tools for infrared pregnancy and heat detection respectively. Other suggested innovations were a sub-slat conveyor belt for easy manure collection (not on the market yet) and the HelixX air cleaning chimney. One experimental test environment has already been set up (see next page) and more will follow to compare outcomes.

According to Holling, the system can be upgraded to a size of a maximum of 400 sows. Beyond this, it would be advisable to break it up in smaller groups again. In addition, the system requires about 8 m2 per sow. Again – it is a model, Holling says, as this is subject to perfectionising too. It’s an ongoing puzzle to find that perfect balance between freedom of movement, public acceptance and economic viability.

Concept study turned into reality

The size of the facility – a 60 sow closed herd – may not look gigantic, but then again, it was exactly what Big Dutchman was looking for to be able to put its concept study ‘Pig Production 2030’ into practice. Ahlers farm, located close to the town of Fürstenau, in Lower Saxony, Germany, was one of the facilities that was threatened due to the 2013 legislation. Refurbishing the pig house to comply with the new European sow housing rules would have been too expensive, but then the German livestock equipment company appeared on the horizon. They told owner Maria Ahlers, 56, early 2012: “Why don’t you work with us on a project? We invest, you keep and sell the pigs, you remain the boss.”

She agreed and as from May 2012, refurbishing started. Once completed in autumn 2012, the farm was populated with pre-inseminated Naima sows (Choice Genetics). The breed has proved to be relatively easy-going. The breeding facility, all in all about 16 x 18 m, is roughly divided by 1 m high walls into two compartments – to the left gestation, to the right lactation.

A small zone in the back is used for insemination. Striking feature: Both in gestation as in lactation, the pigs walk around freely. In the lactation zone, for that reason, more than a hundred piglets of about eight sows run around the sows, do some drinking or group together in a massive piglet hug to keep each other warm. Inside the farrowing pens, both floor heating as heating equipment has been installed. The piglets have been set free from about one week after weaning and can move from their own pen into another by a little flap. Sows will use the larger entrances, marked by a threshold and covered with a large orange cushion, that serves two purposes. It will always ensure that the sow’s claw is directed towards the right place and secondly, it protects her from nasty scratches made by possible sharp edges of the iron pen. The group housing has led to some remarkable behaviour observations, Holling says. Common dunging behaviour is one of these – all in one corner of the facility. Cross-sucking is another. He says, “The piglets have injuries on their cheeks. This is caused by a lot of busy traffic in order to get milk. They don’t care if they get milk at sow A or sow B, so sometimes it’s a bit of a fight who gets the milk. The scratches usually disappear within three days after weaning.”

Holling continues, “Even the sows are communicating with each other. Once one is laying down to offer milk, they seem to say – ‘Come on! Who’s joining me?’ Then we can see more sows lie down together, at least two or three at the same time, so there are always enough teats available.”

Ahlers farm now operates on a four-week system, with piglets being castrated and their tails being cut. Initial outcomes from the first production cycle showed a pre-weaning mortality tending to be just under 20%, with between 9.2 and 10.8 piglets weaned per sow. Holling indicates that this percentage is expected to drop in the process of continuous finetuning. So far, losses could be mostly attributed to crushing as well as early births, the latter probably being the effect of a pathogen.

The piglets are weaned at 21 days (about 6 kg), after which they spend eight weeks inside the nursery next door, until they weigh about 30 kg. Finishing occurs on the same site as well. Unlike the breeding facility, both nursery and finishing facilities have a traditional German set-up, with about 10-15 animals per group. Maria Ahlers says for her the switch to a four-week system was the most profound change. “I now have two intensive weeks and two calm weeks. In addition, there is some more work by computer and there are some more electronics installed.” Now the last thing is only to get better – as a SowCheck system will be installed in the coming months.

***To see more pictures and a video of this facility, please go to www.pigprogress.net/farmvisits/ and search for Ahlers farm.