Guatemala: Swine farming tackles challenges

The external dependence of 90% of grains needed to feed its swine herd as well as animal smuggling from Mexico stir up swine farming in Guatemala. Nevertheless, the country is the biggest producer of Central America, even after a serious crisis that started about five years ago which reduced the number of animals by 15%.

Fertile lands, but hot. This is how the third-largest Central American country can be defined, which has around 280 volcanos. Nature contributes to agriculture as well – Motagua valley, at El Peten department. The region has the most fertile lands for agricultural production. The whole economy is grounded in the strength of the field, which answers for around 40% of the GDP and two-thirds of the exports. Besides, it employs 42% of the economically active population.

Swine farming in Guatemala faces turbulences: dependence on imported grains for animal feeding, high fuel prices and smuggling of animals from Mexico. Up and down as it may go, Guatemala stands out as the largest swine producer in Central America (excluding Mexico), according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

High cereal prices

Despite a higher growth rate than other Central American countries, Guatemala’s swine production is going through one of the worst activity crisis. In the last five years, producers felt compelled to slaughter a huge amount of animals due the high cost of grains.

In 2006, commercial swine production was at a level of 589,000 head. Four years later, it had dropped to 497,000. About 92,000 pigs had disappeared, over 15% of the commercial herd. A similar tendency could be observed in breeding stock, which has been decreasing since 2006, when the country counted 34,000 sows. Anibal Samayoa, manager of the Association of Swine Producers of Guatemala (Apogua), says: “The situation started to worsen in 2008. Nowadays we have about 25,000, and even with prices recovery in 2010, I believe we won’t get back to 2006 level again.”

Before 2006, constant growth figures of 10% could be seen – sudden higher grain prices put an end to that development, Samayoa explains. “The problem is that Guatemala imports 90% of the grain it uses for animal feeding from the USA. This is responsible for 80% of production costs. On top of that came the global crisis that started in 2009.”Swine influenza also tested the country’s swine sector. Although H1N1 2009 was not diagnosed in pigs in Guatemala, pork consumption fell by 80%, as the country is close to Mexico, where the dissemination of the disease started. Samayoa says, “It was a hard blow for pig production, which faced serious problems for nearly three months. After several raising awareness campaigns, people started consuming pork again. Only then we reached pre-pandemic sales and price levels.”Mexico poses one more problem as the frontier is 963 km, which means smuggling of several goods is happening. Among the goods smuggled into Guatemala, live pigs are included, just as e.g. staple grains. Samayoa says: “It is almost impossible for the government to control it, since they form highly organised networks, which have considerable resources.”

Data from the Guatemalan Chamber of Industry point out that smuggling represents 25% of the local trade – and at least 43 ‘blind points’ have been identified. Samayoa adds that the only limiting factor in the case of pigs is its high price in Mexico.

International trade

In regular international trade, El Salvador and Honduras are the main external destinations of the Guatemalan pork. Over the last few years, a preference could be seen for processed products – both countries stepped up their purchases in this market segment by 150%. In fresh meat, the reverse can be seen, since both countries reduced their imports.

Guatemala may become a local exporter of importance as since 2009, exports have also been sent to Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama, but these levels are still moderate – only 80 tonnes of meat in total.The country is also a growing pork importer, mainly of non-processed meat. In order to supply the internal market, the country imported close to 7,000 tonnes in 2009, about 75% coming from the US. Growing imports are related to a recent growth in pork consumption, in this country where beef and chicken are traditionally the more preferred types of meat. The change in attitude towards pork occurred as technically well established farms managed to establish a more optimistic perception with consumers, which are concerned with health issues, diseases and the high fat content on the meat. At the moment, average annual pork consumption is 3.1 kg.

Two producing worlds

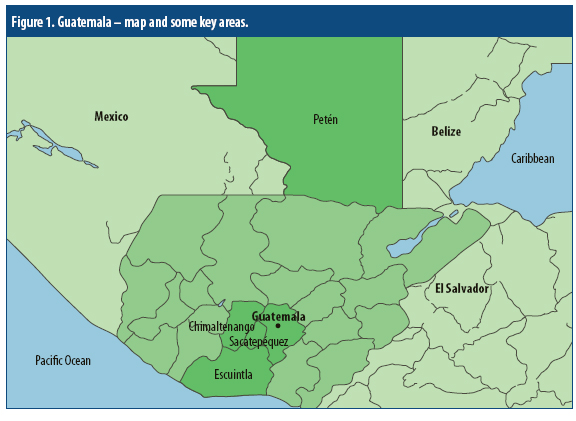

At the top end of the Guatemalan pig world, advanced-level producers can be found, using high performance lineages. Numbers of born alive pigs per sow/ year echo those of other producing countries, with averages between 11 and 11.7. Apogua figures indicate that commercial production can be found at 243 farms, with totals of 25,162 sows, and 498,200 animals. Nearly a quarter can be found in the department of Sacatepéquez; with 6,123 sows. Only five farms have more than 500 sows; the majority of the units have up to 75 sows.

Samayoa says that the more technology-intensive farms, with more than 150 sows, employ known genetic lineages, balanced feeding, modern zootechnical management and have sophisticated and automated facilities. A peculiar feature of the commercial production is that the majority is not integrated with the processing industries, and the producers negotiate prices according to the market demand.At the other end of the spectrum, and counting for a significant proportion of the Guatemalan pig herd, there is ‘subsistence production’. Characterised by rustic systems, and substandard management practices, they allow for the socio-economic inclusion of the rural families.

Exact figures are hard to get by – data from the Guatemalan ministry of agriculture suggest almost 24,000 sows are kept this way – or 48% of the total herd. Yet, Guatemalan Central Bank calculated that the country’s total herd was 2.8 million pigs in 2010. The main pork processor is Empacadora Toledo, headquartered in Guatemala City. The company has been in the business for 40 years, and focuses on filled and smoked products, besides the battered and canned ones. The market leader has been set up to supply both the internal and external markets. The company has highly technified farms of its own, employing superior genetic lines, focusing on producing top-end pigs suitable for the external market. In the late 90s, Empacadora Toledo consolidated itself in the lower class market share and also in the exports to Honduras and El Salvador.

Strong health

Guatemala is relatively ‘clean’, when it comes down to diseases posing risks for international trade, as Foot-and-Mouth Disease and Ausjeszky’s Disease are not part of the scene. In addition, Classic Swine Fever (CSF) has been eradicated after a long process, representing large losses for the sector, but funded with financial help of international organs. Taiwan, for example, financially contributed to eradication programmes for six years. In addition, Mexico donated vaccines, and field and lab research equipment.

The process for eradication of the disease kicked off in 1997 with swine vaccination campaigns at the capital, and at Chimaltenango and Sacatepéquez. From the positive results of those actions, the government put into effect the National Program for the Control and Eradication of Classic Swine Fever in 2004. After five years, the country joined the list of CSF-free countries: Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico and Panama.However, an outbreak of CSF only three months later (at the beginning of 2010) at a farm at the department of Escuintla led both Honduras and El Salvador to close the importing of fresh and processed products.

Samayoa says, “We acted swiftly. We complied with the animal health recommendations set forth by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and were able to control the disease.” The reopening of the trade, he explains, was done immediately by Honduras. Negotiations with El Salvador took longer.It seems that the Guatemalans learnt their lesson. As with volcanic eruptions, diseases appear when they are least expected. In order to avoid reoccurrence of the disease, the Ministry of Agriculture keeps epidemiologic brigades over the whole country, answering to reports of health problems and offers the support of specialised professionals. So now it’s the next concern: Defeating resistant Mycoplasma.