Feeding strategies for profitable growth in finishers from 30kg

Successful fattening is a balancing act between feed intake and conversion.

First you have to get fattening off to a good start by ensuring piglets from the weaner unit are strong and healthy. A clean, disinfected and dry stable with the right temperature and ventilation and access to fresh feed and water is essential. Remember to remove old food or dirt from the troughs, as this will have a negative impact on pig appetites and, consequently, daily weight gain.

Second, you need good stable routines for regularly checking the pigs’ weight and making necessary adjustments.

Thirdly, strong and healthy weight gain depends on the quality of the feed. This is about ensuring the pigs gain all the necessary nutrients at the right levels, free of toxins and ground to the right size.

Setting yourself up for the best returns

The key is to achieve the optimum slaughter weight per pig without spending more time than necessary in the stable, as this will reduce the kilos produced per square metre of pen space. At the end of the day, you need to gain the best possible return from the capital investment in the barn.

Market conditions typically determine the best slaughter weight for your business. If feed prices are low, a higher slaughter weight may be preferable to get the best price. On the other hand, low piglet prices may favour a lower slaughter weight to reduce the cycle time in the barn.

Regardless of the weight strategy you choose, the feed will typically still account for two-thirds of your production costs. Even a small improvement in feed efficiency can have a significant impact on the financial outcome.

Regulation of feed intake

When feed is supplied ad libitum, the pigs regulate their intake according to their sense of satiety, which is either physically or chemically regulated.

In pigs up to 50-60 kg, it is primarily the capacity of the gastrointestinal tract that limits feed intake. Satiety is reached, and feed intake reduced.

In heavier pigs, feed intake is regulated by a high concentration of nutrients such as glucose, amino acids and fatty acids in the blood, which influence hunger and satiety (Nielsen, N.O. 1987. Meddelelse nr. 125, Landsudvalget for Svin). Exactly when this chemical regulation occurs depends on the pig’s genetic ability to turn nutrients into growth. Pigs with high growth capacity can eat more before chemical regulation reduces feed intake.

The fattening period, then, can be divided into two stages:

- 30-60kg – maximum use of growth potential

During the first part of the fattening period, pigs have low feed consumption per kg of weight gain. At this stage, ad libitum feeding is crucial - 60 kg to slaughter – weight gain optimisation to reduce feed conversion and costs and make efficient use of space.

Feed intake should be limited. Although ad libitum feeding systems include several options for restricting intake, behavioural problems may arise if the feeding dispenser becomes empty or feeding breaks are too long.

Balancing conversion and utilisation

Daily feed intake affects weight gain, lean meat percentage and feed conversion. Increased feed intake leads to higher growth, until a certain stage is reached when the potential for meat deposition becomes limited. Consequently, excessive feed intake leads to high conversion but poor feed utilisation, as fat deposition requires more energy than meat deposition. When feed intake is very low, feed conversion is also high because most of the energy consumed is used to maintain the body. The exact ratios depend on the sex of the pigs and the genetic level of meat production.

In each case, the optimal feed consumption from an economic perspective depends on the price, target growth and meat percentage.

Experiments have shown that a better lean percentage and 3% increase in weight gain can be achieved if male and female pigs are fed separately. In mixed groups, the males restrain the gilts, reducing their feed intake. Males eat more than females throughout their growth period, have a higher feed conversion rate and grow faster.

Why phase feeding works

Feed must be formulated to meet the nutritional needs of finishing pigs and ensure the most cost-effective feeding.

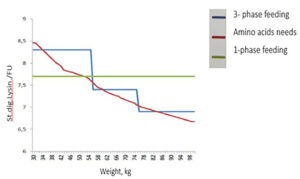

Phase feeding involves the use of multiple mixes to meet the animals’ changing nutritional needs. Feeding may cover three or more phases, with a reduction in the content of amino acids through the entire growth period. If one feed recipe is used during the entire fattening period, pigs receive too few amino acids at the beginning and too many at the end.

Source: SEGES

Phase feeding ensures optimal protein utilisation

Farmers that choose phase feeding need to invest more in feed equipment and pay more attention to handling several types of feed. The advantage is that pigs can be given a better mix at the beginning while the average price of the feed is reduced due to the lower cost of the finisher recipe. Phase feeding also gives better control of feed conversion.

In Denmark, for example, amino acid guidelines are based on farm-specific conversion rates and the desired percentage of lean meat. Actual levels of amino acids and energy should be determined as the economically optimal level for raw material selection and price relationships.

*Based on the energy content 1.06FUgp/kg feed

Choosing the best grind

The feeding strategy can affect pig stomach health. Possible strategies are shown below in order of priority:

- Feed mix, where 10-20 % of grain is not heat treated or pelletised, possibly expanded feed (coarsely milled feed mix that is heat treated but not pelletised)

- Pelletised feed with the grain part coarse milling.

In a feeding trial, there was no difference in the incidence of wounds and scars in the white part of the stomach, regardless of whether pigs were fed once or twice a day with the same amount of feed. By comparison, ad libitum feeding with pelleted feed resulted in most scars and ulcers.

Pigs fed mash are much less likely to have stomach wounds and scars. Although feeding once or twice daily with the mash feed gave fewer wounds and scars than ad libitum mash feeding, the differences were not statistically different (Seges/2014/medd1014).

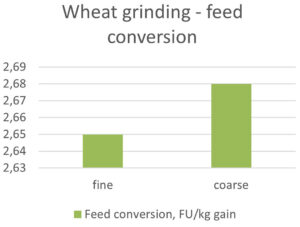

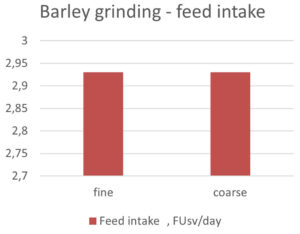

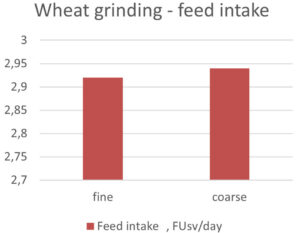

From fine to coarse

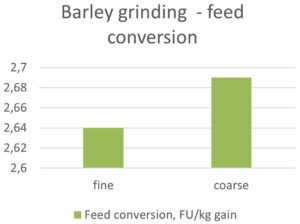

For growing pigs, feed should be ground as fine as possible to obtain the lowest feed consumption. Maximum 80% below 1mm will help prevent ulcers. In practice, the recommendation is to start with the finest particles and to gradually increase the percentage of coarse particles until a good balance is achieved between feed conversion and stomach health.

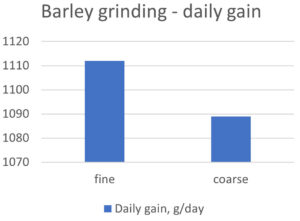

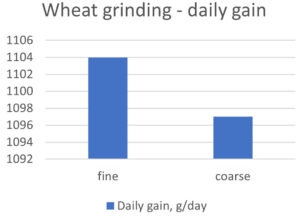

Fine grinding gives the highest productivity for wheat and barley but may increase the risk of gastric health problems. Tests have shown that the annual production value of slaughter pigs could be safely improved using finely ground cereals (88% below 1 mm) compared to coarsely ground cereals (50% below 1 mm). Higher daily growth was also seen when finely ground barley was compared with coarse milling (Seges/medd 1012/2014).

The improved feed utilisation achieved with fine milling can be explained by better utilisation of the starch. This has been confirmed through analyses of the starch content of pig manure.

When solving stomach health problems, there appears to be no difference whether barley or wheat are ground more coarsely.

- Fine grinding: 80% below 1mm

- Coarse grinding: 50% below 1mm

Summing up the challenges

Ensuring that pig feed is efficiently converted into increased body weight is always a challenge. To sum up, here’s an overview of the factors that can affect the all-critical feed conversion rate – and your profits.

- Feed wastage – proper feeder regulation is necessary. A metal plate under the feeder can prevent feed from falling down into manure.

- Health status – sick pigs, for example with gastric ulcers or infections, consume less feed, compromising feed conversion.

- Feed availability – pigs fed the wrong diet or with limited access to feed, perhaps due to overcrowding

- Feed quality – poor quality feed may be oxidated or contain mycotoxins.

- Environmental conditions – bad ventilation and overly high temperatures can reduce feed consumption, while consumption will go up if temperatures are too low. Feed conversion is impacted either way.