US pig industry may feel the effect of new tariffs

Donald J. Trump will be residing in the White House in Washington, D.C. once again, as from January 20. A number of things will most certainly change – one of them includes tariffs. Those may not be good news for the US swine industry.

The newly elected US president Donald Trump has announced that he will set new tariffs on imports from China, Mexico and Canada. On his own social network Truth Social he wrote that it would happen on the first day of his presidency, “On January 20th, as one of my many first Executive Orders, I will sign all necessary documents to charge Mexico and Canada a 25% Tariff on ALL products coming into the United States.”

He claims that this will force these countries to crack down on illegal immigration and drug smuggling into the USA. He also said, “We will be charging China an additional 10% tariff, above any additional tariffs,” unless the country did more to prevent fentanyl smuggling. For any trade analyst and most commercial operators, these threats are unsettling. They have to be taken seriously – or do they?

Many sectors will be hit

To be clear, the threat of tariffs will hit many sectors of the US economy. China, Mexico and Canada account for about 40% of the US$3.2 trillion of goods it imports each year. The list of imported goods from these countries includes: oil, car parts, electronics, sugar, fruit and vegetables, pork and live pigs. Canada is the largest supplier of crude oil to the USA with more than 3.8 million barrels per day, or 60% of US crude oil imports.

One analyst claimed that a 25% tariff on Canadian oil would have huge impacts on gas prices in the Great Lakes, Midwest and the Rocky Mountains. Another analyst noted that Mexico is the largest exporter of vehicles, vehicle parts and vehicle accessories to the USA – larger than any other country. Patrick Anderson, CEO of Anderson Economic Group, a consulting firm in Michigan, told the New York Times: “There is probably not a single assembly plant in Michigan, Ohio, Illinois and Texas that would not immediately be affected by a 25% tariff.”

The 2018 experience suggests that federal tariffs were costly to US farmers, consumers and taxpayers and even counterproductive

The button was pressed before

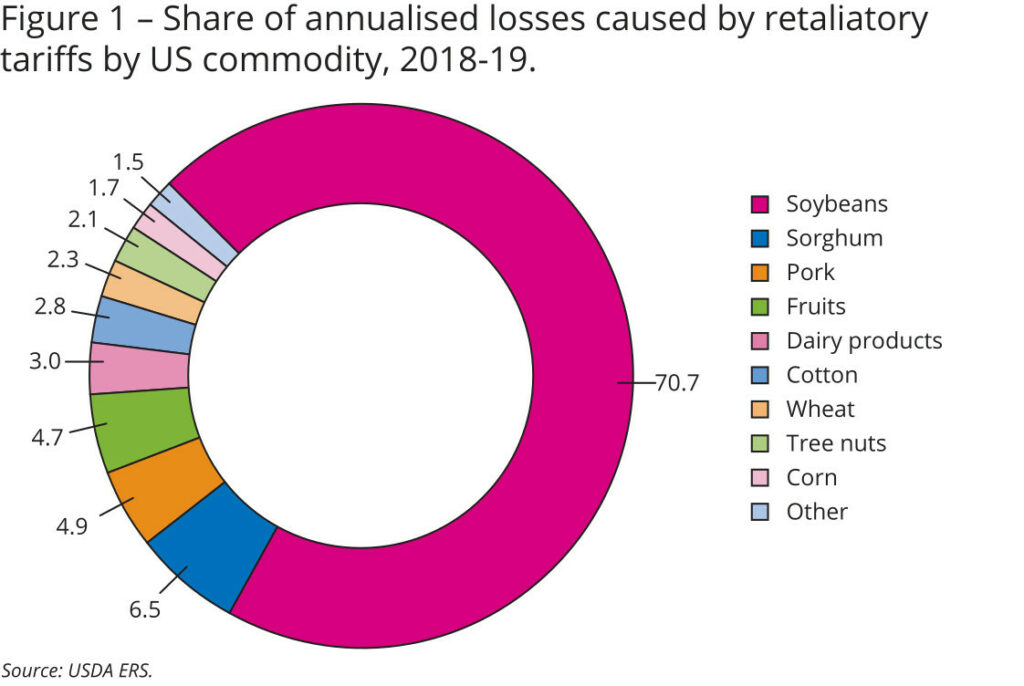

As if these reports from reputable analysts and business groups were not alarming enough to make Trump think twice when considering the impact of tariffs, it should be remembered that it has happened before. There is evidence available of what happened the last time he pressed the “tariff button”: see, for example, the publication by the USDA, The Economic Impacts of Retaliatory Tariffs on US Agriculture. Figure 1 (from that USDA report) identifies how various commodities were hit by Trump’s tariffs in 2018/2019. After president Trump imposed tariffs on some of China’s exports into the USA, during 2018, Beijing introduced its own 25% tariff on US$50 billion worth of US goods.

The most prominent casualty of this action was US soybean exports, i.e. US farmers were caught in the cross fire. US soybean exports to China collapsed to less than half the previous levels, from 28.7 million tons in 2017-2018 to 10.3 million in 2018-2019, as the Chinese bought Brazilian and Argentinian soybeans. US soybean exports tried to find new markets, but were not totally successful. Soybean exports in the 2 years of this trade war declined by about 20% and soybean prices in the USA dropped by almost 20%. A federal market facilitation programme costing the US taxpayer US$23 billion was introduced to cushion the blow to American farmers. Thus, in the 2018 example, US farmers, consumers and taxpayers paid for federal policies. The USDA estimated that the United States lost around US$27 billion in farm exports.

Mexico and Canada

In the introduction above it is observed that Mexico and Canada are important markets for, and suppliers of many products and inputs to the USA. For pigs and pork, the USA is both an exporter and importer – exporting pig meat to Mexico (its largest export market), and Canada (and China, of course), and importing pig meat and live pigs from Canada. Those are important destination and supplying markets for the US pork sector.

So important that, all in all, the pig meat exports to these countries provide over half the value of each hog slaughtered in the USA (calculated by the US meat export federation). In 2018, president Trump’s tariffs were on steel and aluminium and, at that time, this prompted Mexico to announce new tariffs on several US-produced products in response.

Those retaliatory tariffs were targeted on whisky, cheese, steel, bourbon and pork – US farmers were again having to pay for the federal trade policy. As Tables 1 and 2 show, Mexico is now the biggest customer for US pork, so even higher retaliation could be expected in round two of a trade war. If he will do what he promised, as from January 20, president Trump will apply a 25% tariff on Mexican-sourced imports across the board even before any retaliatory tariffs.

Where is it all heading?

Serious commercial operators will want to know where this is all heading. The 2018 experience suggests that federal tariffs were costly to US farmers, consumers and taxpayers and even counterproductive.

Further, all the countries that may receive tariffs have said they will introduce retaliatory tariffs if the plans are not taken off the table, similarly to 2018. In turn that would likely raise the prices of oil, gas and car parts and a host of other goods. US pig and pork producers’ costs and revenues would be hit as demand drops in their markets after US pork exports are hit by retaliatory tariffs in the destination markets. For Canada’s live hog exports, tariffs would hike US producers’ costs in the north-western States and drive down live prices in the short term as the supply chain adjusts.

Overall, the implications of the threats of introducing tariffs are so large and damaging that it’s difficult to take the idea seriously. It would be prudent meanwhile to stress resilience in business planning.