Deliberate transport of wild pigs causes wider spread in US

The wild pig problem in North America remains serious. Populations have grown over time and are still growing. Wild pigs are a potential vector for diseases that affect commercial pigs. They can also cause extensive damage to crops, native ecosystems and various wildlife populations.

Hunting of wild pigs only causes them to move to other areas more quickly, adopt nocturnal behaviours and so on. Some people feed pigs in order to attract them so that they can be more easily trapped or shot, in order to eliminate them or for sport hunting, and this could help populations grow. Also, importation of these pigsfrom state to state has been going on for years in some areas, a practice likely being carried out to create populations for sport hunting.

Deliberate transport

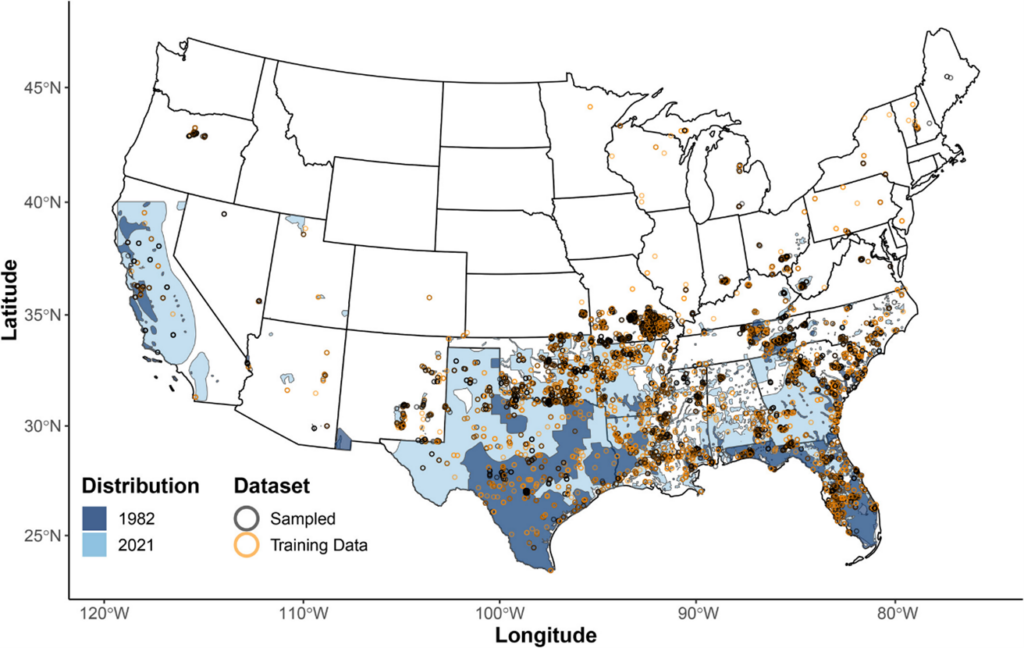

However, new research by scientists at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA National Wildlife Research Center and University of Saskatchewan in Canada has demonstrated that “purposeful human-mediated movement of feral swine has contributed to their rapid range expansion over the past 30 years. Patterns of deliberate introduction of feral swine have not been well described as populations may be established or augmented through small, undocumented releases.”

By leveraging an extensive genomic database of almost 19,000 samples, the scientists used AI software to identify translocated (moved) feral swine across the US. “We classified 20% of sampled animals as having been translocated and described general patterns of translocation,” explains Dr Rachael Giglio and her colleagues in their paper. “These findings unveil extensive movement of feral swine well beyond their dispersal capabilities, including individuals with predicted origins >1000 km away from sampling locations.”

New bill

In Ohio, the state’s House of Representatives recently unanimously passed House Bill 503, which will require people who shoot a feral pig to notify USDA Wildlife Services within 24 hours. “Introduced earlier this year, the bill which now must pass the Senate would prohibit the importation and hunting of feral swine in the state and ends the practice of garbage feeding, both of which pose serious disease risks to the state’s swine herd, including the possibility of introducing African swine fever,” states the Ohio Pork Council. Other agricultural organizations also strongly support the bill.

It is already illegal to transport, release, or hunt feral hogs, and landowners must report suspected feral pig sightings, in other states like Nebraska.

Pilot project

In a small area of South Carolina, last year the USDA wrapped up a 3-year programme where staff removed 860 wild pigs from 19 properties during year 1, 290 wild pigs from 17 properties in year 2 and 125 pigs from 13 properties in year 3 (mostly by trapping).

A team of scientists who monitored populations during and after the project, found that this resulted in a 70% decrease in population.