Using the vet efficiently (part two)

Here are some suggestions for two categories of pig producers which I do not find in the textbooks.

First, the welcome dwindling band of producers who rarely use the vet. On grounds of cost, distance, and – I still encounter this reason, pig farmers saying: “The drug and vaccine firms keep me straight.” It is no coincidence that these producers are usually benchmarked in ‘the bottom third’ of physical performance.Secondly, those converted to regular veterinary involvement on their farms but who are hesitant, usually on grounds of additional costs, to engage in ‘disease-profiling’ which I shall describe later. These producers, so my records suggest, tend to be in the ‘top third’ in performance terms. There is also growing evidence that this group of producers in countries still plagued by PRRS seem to encounter less of it – but that is a story for another column.

The bottom third – preventable disease

Preventable disease in all its breadth seems to cost them up to 30% of gross margin. In tough times, like the present high feed prices, this can be the difference between insolvency and survival.

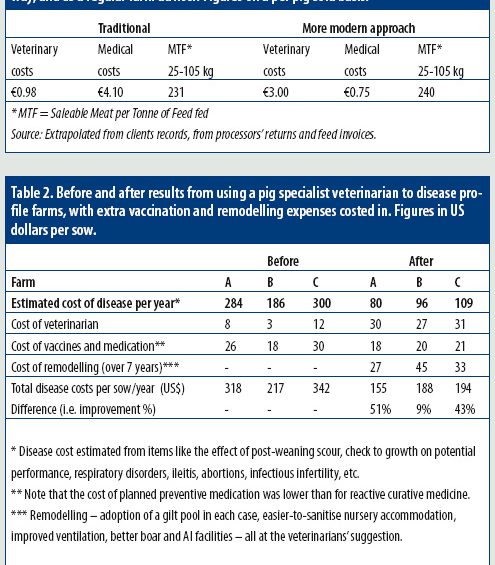

Do veterinary practices publish their success rates in controlling/ reducing disease levels? If so, I’ve not come across them. So take a look at Table 1, which I compiled in 2006, but is equally – if not more – applicable today with feed costs so much higher.Table 1suggests that even if veterinary and medical costs are as high as €5 per finished pig – these were mainly ‘bottom third’ producers – this was still only 8% of their total costs. Paying three times more – which understandably puts people off – for a regular visit by the vet, his skilled advice, his staff training and encouragement and all his monitoring and measuring, should only increase costs by €2 per pig, which is a little over 3%. Surely a good bargain?

The next step up – disease profiling

Disease profiling was first introduced to me on RHM Agriculture’s Deans Grove farm by our pig specialist vet, the late Terry Heard, who visited about every six weeks on contract and did at least 11 tests on the animals and bacterial counts, i.e. swabs, on the unit’s surfaces and equipment (fans are often omitted and, unfiltered, can be a source of disease entry).Later I came across the concept being used by several top pig veterinary practices in the USA, from which Table 2was compiled.

Disease profiling

Disease profiling is a technique used to enable the veterinarian to keep abreast of any changing disease pattern on the farm and in the locality. Is this important? It seems so, as the pattern of disease challenge varies from month to month, and resultant advice on precautionary/advance protective protocols should change with it. This is vital when introducing replacement breeding stock as it keeps pace with measures needed to match changing immune shields. We were a closed herd at Dean’s Grove, but the large US herds generally were getting replacements either from outside or from their own in-house grandparent or multiplier farms, where the sub-clinical disease patterns were still different. Table 2 shows that in their case the concept paid and there is no reason to suggest that the same would not be true anywhere else today.