It’s difficult to transfer MRSA by physical contact

It appears to be virtually impossible for pig farm house visitors to contaminate others outside the pig facility with livestock-associated MRSA.

That was one of the conclusions drawn by Danish researchers from Statens Serum Institute and Denmark’s National Research Centre for the Working Environment.

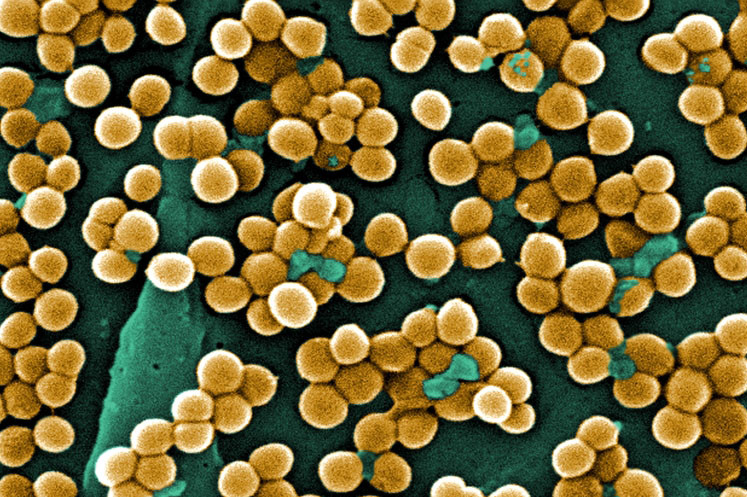

They concluded that the increase in human methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriage among the volunteers with pig contact seems to be dependent on the increased concentration of airborne MRSA of the surrounding air and not directly on the physical contact.

Read everything about swine health in the Pig Progress Health Tool

Investigating frequency and duration of MRSA carriage

In a recent publication in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, the researchers described that their objectives were to investigate the frequency and duration of MRSA carriage in human volunteers after a short time exposure in a swine farm. The experimental study included 34 human volunteers staying 1 hour in an MRSA-positive swine farm in 4 trials.

In a summary of the research on the website of the American Society for Microbiology, was stated that in each of the 4 trials, the volunteers spent an hour at a MRSA-positive swine farm. Each volunteer spent 2 trials as an ‘active’ participant, catching and constraining the pigs, and taking samples from them. In the other 2 trials, as ‘passive’ participants, volunteers simply stood around in the same room as the pigs. That structure is called ‘crossover’; this was the 1st crossover study to examine livestock to human transmission of MRSA.

In 2 of the trials, the influence of farm work involving pig contact was studied using a cross-over design. The quantity of MRSA in nasal swabs, throat swabs, and air samples were measured at different time points and analysed in relation to relevant covariates.

94% of volunteers acquired MRSA

This investigation showed that overall 94% of the volunteers acquired MRSA during the farm visit. About 2 hours after leaving the stable, the nasal MRSA count had declined to unquantifiable levels in 95% of the samples. After 48 hours, 94% of the volunteers were MRSA-negative. Nasal MRSA carriage was positively correlated to personal exposure to airborne MRSA and farm work involving pig contact and negatively correlated to smoking.

The researchers also concluded that no association was observed between MRSA carriage and face touching behaviour, nasal methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) carriage, age, and gender. MRSA was not detected in any of the throat samples either.

Elucidating contributions of airborne MRSA levels

Explaining the wider context of the research, the authors wrote that transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from animals to humans is of great concern due to the implications for human health and the health care system.

The experimental approach made it possible to elucidate the contributions of airborne MRSA levels and farm work on nasal MRSA carriage in a swine farm. Short-time exposure to airborne MRSA poses a substantial risk for farm visitors to become nasal carriers but the carriage is typically cleared within hours to a few days. The risk for short-time visitors to cause secondary transmissions of MRSA is most likely negligible due to the observed decline to unquantifiable levels in 95% of the nasal samples already after 2 hours.

The MRSA load in the nose was highly correlated to the amount of MRSA in the air and interventions to reduce the level of airborne MRSA or the use of face masks might consequently reduce the nasal contamination.

The research was carried out by Øystein Angen, Klaus Rostgaard, Robert Skov and Anders Rhod Larsen, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark; and Louise Feld and Anne Mette Madsen, National Research Centre for the Working Environment, Copenhagen, Denmark