What role do insects have in pathogen transmission?

Insects could possibly be a mechanical vector for transferring pathogens. Especially now larvae also increasingly serve as animal nutrition, this may develop into an unintended risk for the health status of a herd. Scientists from a Belgian university examined existing literature to gain insight into their influence on the spread of pathogens.

Various insect species can pose a health hazard for both animals and humans by acting as vectors of pathogenic agents. Flies, such as the house fly or the stable fly, frequently visit animal farms due to their tendency to inhabit and reproduce in manure, spoiled feed, and other organic materials on farms. Beetles generally exhibit less mobility and slower development compared to flies. In addition, the larvae of beetles and flies are used on farms as an alternative source of protein for pigs.

While scientific research indicates that incorporating live insect larvae into pig diets can positively impact their health and well-being, there may also be negative health effects due to pathogen transmission. In high-risk scenarios where pigs do not consume all the presented larvae, the surviving larvae may persist and develop into adults. These adults can then spread to other structures on the farm, and in the case of fly larvae, potentially transmit pathogenic agents even to neighbouring farms.

Literature review on pathogens

For this reason, researchers at Ghent University in Belgium, supported by experts from the Netherlands and India, carried out a systematic literature review of studies carried out in Europe and North America. The goal: uncovering studied potential routes of transmission of pathogens by flies, beetles or their larvae.

The team identified 39 relevant studies for the review. Of these 39, the country contributing most of the studies was Germany (8 studies), followed by the United States (7) and Denmark (4). In addition, over 87% of the studies examined the involvement of flies. A possible insect transmission of 26 different porcine pathogens had been studied, the team found. The focus was mostly on African Swine Fever virus (ASFv), followed by antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli.

The Belgian team assessed the outcomes of each study and classified each connection as “proven,” “likely,” “potential” or “unlikely.” The researchers defined each category of evidence on the basis of the type of study, the type of diagnostics used and the amount of evidence gathered. For instance, “proven”, the strongest category, meant there would be:

- direct evidence of pathogen transmission from insects to pigs;

- a high causal relationship established;

- pathogens isolated from both insects and pigs in controlled environments;

- detailed epidemiological analysis showing clear transmission pathways.

The category “proven” appeared 3 times. Below are highlights of the literature study.

Flies & Viruses

Flies have been associated with the possible transmission of 9 viruses in research. Of 3 of the viruses, the respective researchers reported that transmission was “proven.”

ASFv: Transmission “proven” via stable flies

The list of studies on the potential transmission by insects was the longest in relation to ASFv. 11 studies zoomed in on 14 possible routes involving insects. Only one study out of these 11 provided “proven” evidence of transmission. That was a Danish experimental study from 2018 by Ann Sofie Olesen and her colleagues from the Technical University of Denmark. They observed infection after pigs ingested 20 blood-fed stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans). In addition, the researchers found that transmission was “likely” in 8 additional routes which included again the stable fly, house fly (Musca domestica), horse flies (Haematopota species) as well as biting midges.

Interestingly, only one study from Germany (2018) could not confirm virus transmission, an outcome possibly related to the type of flies that was studied, namely blowfly larvae (Lucilia sericata).

PRRSv: Transmission “proven” via house flies

Another “proven” connection occured in the studies on insects and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus. Back in 2009, research from Andrea Pitkin at the University of Minnesota, USA, demonstrated that under suitable conditions, house flies can acquire PRRSv from infected pigs, internally harbour the virus and transport it over substantial distances, as observed in commercial swine industries.

2 more studies zoomed in on the connection between PRRSv and the transmission via insects. In a related experimental study from 2015, PRRSv persisted in stable flies for at least 10 days post-ingestion. This suggested “potential” evidence of transmission. A third study (2011), however, concluded that stable flies were “unlikely” to transmit PRRSv between pigs during blood-feeding.

VS New Jersey virus: Transmission “proven”

Worth noting in this context is a virus that is not making the most headlines in swine reporting: Vesicular Stomatitis New Jersey virus (VSNJv). Transmission of this pig virus by black flies (Simulium vittatum) was “proven”. An experimental study in the US state of Georgia demonstrated that black flies can mechanically transmit VSNJv to a naive host through interrupted feeding on a vesicular lesion from a previously infected host. In this study, 1 animal exhibited clinical disease while the other remained asymptomatic. The Georgia team attributed this variation to individual differences in susceptibility to infection and clinical outcomes.

PCV2: Transmission “likely” via house flies

Worth mentioning, from 2 studies, is Porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV2). An experimental study conducted in the UK pointed out house flies as having a high potential for carrying and transmitting PCV2 on-farm. The study attributed this to their life cycle. This closely aligns with pigs and their surroundings. Another study proposed that flies may be “potential” vectors for the transmission of PCV2. Beyond their role as vectors, they could act as chronic “stressors” for affected animals.

PEDv: Transmission “likely” via house flies

According to a study from Ukraine, the identification of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhoea virus (PEDv) in the homogenate derived from house flies captured during the disease outbreak provides “likely” evidence of the involvement of house flies in the mechanical dissemination of the PEDv to farm environment. However, viral replication was absent from their bodies.

Other viruses

The literature review contained 4 more viruses that insects could possibly transmit. In those cases, the outcome was that the connection was “potential.” This concerns hepatitis E virus, Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus (PRCv), senecavirus A and swinepox virus.

Flies & bacteria

Flies were associated with the possible transmission of 13 bacteria to domestic pigs. Unlike with the viruses, none of the transmission routes were “proven,” but the vast majority ended up as “likely.” As with many bacteria, research was restricted to 1 study only.

AMR bacteria: Transmission “likely”

The Belgian team compiling the literature zoomed in on a dangerous class of bacteria: antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria. This characterisation runs through all types of bacteria. And yes, transmission of antimicrobial resistant bacteria via insects is “likely,” the research team concluded on the basis of available literature. AMR E. coli attracted most attention in 4 different studies where transmission was considered “likely” via house flies and stable flies. Studies also demonstrate the likelihood of AMR enterococci and AMR entereobacteriaceae by the house fly.

In addition, a study from Germany suggests that flies can act as vectors for AMR enterobacteriaceae, potentially introducing new pathways for the transmission of carbapenemase-producing organisms.

In this context, it is good to mention methicillin-resitant Staphylococcus aureus variety, which can also exist in livestock (known as LA-MRSA). Studies from 2021 and 2023 considered transmission likely via house flies and stable flies.

E. coli: Transmission “likely”

At least 3 studies looked into the transmission of Escherichia coli – both by stable flies and house flies. An Austrian study from 2020 found that E. coli was present in stable flies in 7 out of 20 farms (35%). Additionally, a German study from 2009 confirmed that both types of flies carried E. coli strains. Thereby, these studies indicate the “likely” transmission of E. coli through flies.

Important to mention is a special type of E. coli – the form that is resistant to antimicrobials. Various studies have been carried out to establish whether or not the AMR E. coli variety could be transmitted and the answer in four studies appears “likely.”

Campylobacter: Transmission “likely”

3 studies zoomed in on Campylobacter species. A German study from 2009 concluded that there is a “likely” transmission route for Campylobacter species through house flies as well as stable flies. The flies that carry the bacteria in their intestines and on their exoskeletons can serve as a route for mechanical transmission. A third study from 2013 generally concluded a potential transmission by house flies.

L. intracellularis: Transmission “likely”

Both house flies and the larvae of rat-tailed maggots (Eristalis species) were identified in 2 studies as having a high potential for on-farm carriage and transmission of L. intracellularis. The presence of Lawsonia-positive flies on specific farms suggests a potential for farm-to-farm mechanical transmission, especially as adult house flies can easily move between sites up to 7 km apart within a three-day period.

Staphylococcus species: Transmission “likely”

Special attention for Staphylococcus – 2 studies concluded that a transmission by flies was likely. A German study showed the ability of flies to carry S. aureus and an Austrian study highlighted the role of stable flies in the transmission of the S. xylosus. Thus, the transmission of Staphylococcus species through flies is considered “likely.”

Other bacteria

The literature review contained 8 bacteria on which 1 study focused. These concerned Clostridium difficile (transmission potential), Klebsiella oxytoca (likely), Proteus mirabilis (likely), Salmonella species (likely), Salmonella enterica (potential), Staphylococcus xylosus (likely) and Yersinia enterocolitica (potential).

Flies & parasites

In the literature studied, flies were associated with the possible transmission of 4 parasites to domestic pigs. In all cases, transmission by house flies was evaluated as “likely.” The examination of both wild flies and laboratory transfer experiments demonstrated that house flies not only ingest but also carry pig parasite eggs and larvae.

A German study conducted by Maike Förster and her team at the Heinrich-Heine University of Düsseldorf, Germany, in 2009, identified 4 different pig-specific parasitic nematodes (Ascaris suum, Strongyloides ransomi, Metastrongylus species and Strongyloides species) isolated from house flies caught in a pig pen. The same nematode species (excluding Metastrongylus species) were detected in pig faeces.

Beetles & pathogens

The amount of scientific literature on beetles on farms and their potential role in the transmission of pathogens is not as large as that on flies. Beetles were associated with the possible transmission of 2 viruses (ASFv and PRCv) and 1 bacterium (C. difficile). In 1 study, the larvae of beetles were described as parasites.

ASF virus: transmission “likely”

Only in study the transmission by parasites was considered “likely.” In that study, a PCR-positive sample was detected for ASFv in rove beetles (Gyrohypnus, Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). It was also found outside a domestic pig farm building during an ASFv outbreak. Given that Staphylinidae beetles can disperse over considerable distances, the detection suggests their potential role in the dissemination of the virus.

Another study from Spain involving yellow mealworms larvae could not confirm virus transmission. The authors however could not rule out the possibility.

Discussion & conclusion

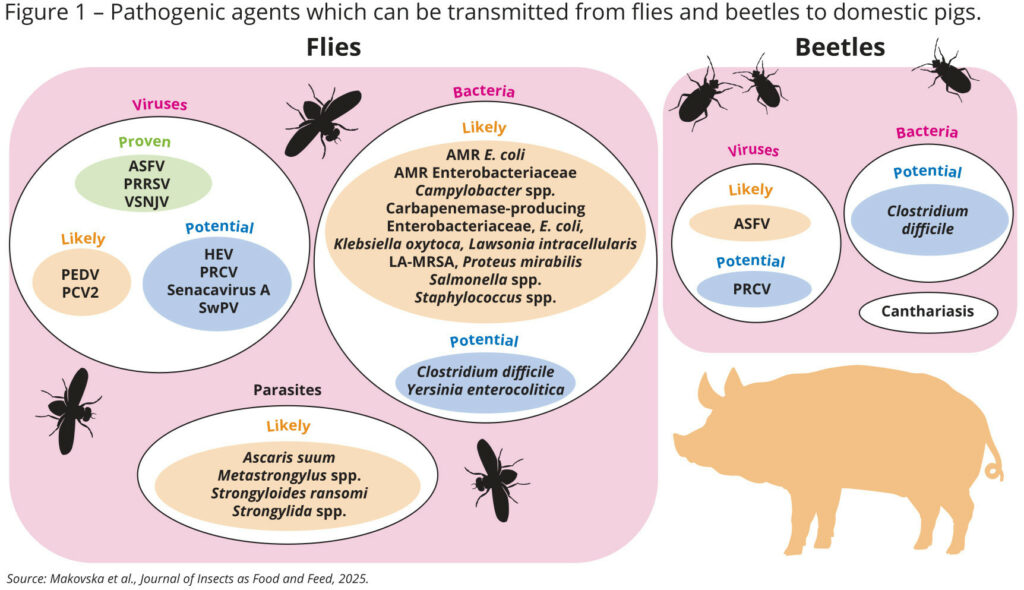

The authors of the study note that flies can transmit 26 distinct pathogenic agents to pigs, while beetles transmit only 3. Both flies and beetles transmit 3 of these agents (ASFv, PRCv and C. difficile). In general, only 3 studies provide conclusive evidence of pathogenic agent transmission. All of these focus on viruses (ASFv, PRRSv, and VSNJv). For 18 pathogens (17 transmitted through flies and 1 through beetles) the transmission evidence is considered “likely”. The literature analyses for 8 pathogens suggest that flies and beetles may “potentially” play a role. 2 studies conclude “unlikely” transmission (in the case of ASFv by blowfly larvae and PRRSv by the stable fly).