Stabilising the microbiota – essential for gut health

Several changes in the life of a piglet occur during weaning: removal from the sow, transition from liquid to solid feed, transport to another facility and mixing of litters. All these cause stress and disruption of the established microbiota. A post-weaning nutritional intervention could help to prevent diarrhoeal disease.

The microbiota refers to the wider range of micro-organisms that populate the inside of any living organism. The microbiota produces metabolites that may pass the gastrointestinal wall and subsequently enter systemic circulations. These “xenometabolites” might be beneficial or harmful to the host.

Microbial activity in the intestinal tract can limit animals’ growth efficiency as some elements in the gut’s microbial community compete with the host for nutrition. Additionally, undigested protein, endogenous protein or microbial protein that bypass the small intestine are available for the microbiota in the caecum.

Toxic metabolites produced during this fermentation can affect intestinal cell turnover and growth performance. Microbiota can accelerate turnover rates of enterocytes and goblet cells, causing high cell turnover and an increased rate of metabolic and protein synthesis. This creates a larger population of immature cells that are less efficient in absorbing nutrients. Finally, intestinal microbes decrease fat digestibility by deconjugating bile acids. Catabolism of bile acids in the gut causes a decrease in lipid absorption and produces toxins that inhibit piglet growth.

A diverse, stable microbial community is linked to a better feed conversion ratio in healthy and in challenged piglets. Higher diversity of microbial genera has been associated with improved resistance and better production performance in animals. This is possibly associated with the different roles that gut microbiota play in the gastrointestinal tract. Specific bacterial genera are known to each have a set role in the gastrointestinal tract such as:

the generation of specific compounds;

multiple effects on digestive processes and gut integrity;

development of host-defence mechanisms; and

resistance against pathogen colonisation by blocking attachment via competitive exclusion.

Stabilising the microbiota

One method to tackle microbial activity is to apply a synergistic blend of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA), slow release C12, target release butyrates, phenolic compounds and organic acids with high pKa value. All this can be found in Presan, a Selko brand. This product not only stabilises the microbiota, but also supports strengthening of the gut barrier function (see Box).

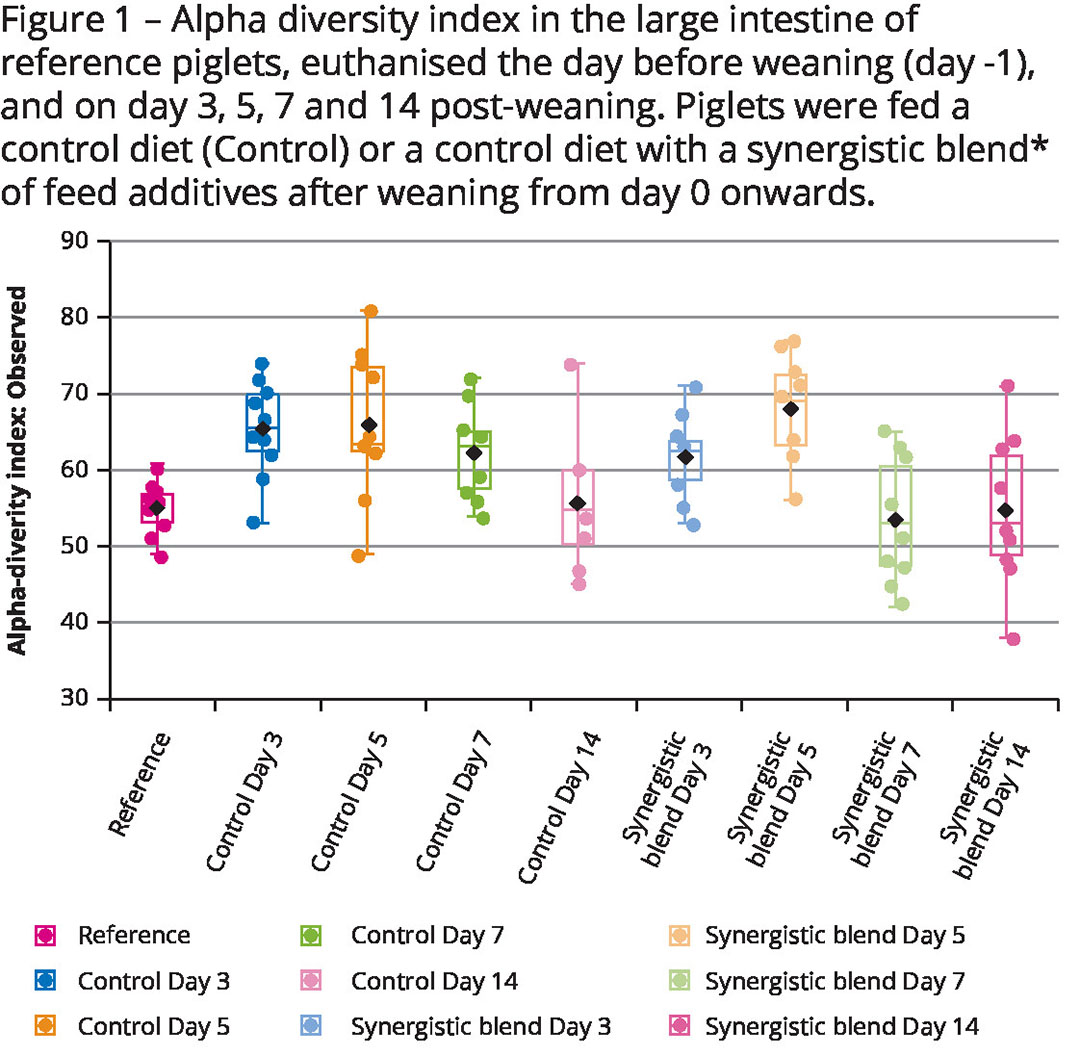

Recent studies have revealed new insights on the effect of this synergistic blend in pigs. For example, seven days after weaning, the alpha diversity in the large intestine for pigs fed this synergistic blend returned to the level before weaning, whereas the piglets in the control group needed until day 14 to recover to the pre-weaning level (Figure 1). Additionally, lower variability in the group receiving the feed with this blend demonstrated that the blend supports a more effective assembly of the post-weaning colonic microbiota, to a more uniform microbiota composition.

In addition, weaned piglets fed the blend had a higher abundance of Lactobacillus in the small intestine. These bacteria help with the fermentation of tryptophan into indole propionic acid, supporting gut barrier function. As Lactobacillus species are important members of the porcine microbiota, and long known to be sensitive to host stressors, their increased abundance in piglets fed the blend following the disruption of weaning indicates a protective effect through shaping a gut environment that allows earlier Lactobacillus expansion post-weaning. Along with the increased amount of Lactobacillus bacteria, there was a decline in variation of opportunistic bacterial species not typically native to the gut, suggesting a more stable microbiota population had been established.

These results suggest that the intestinal microbiota of piglets fed the diet with the blend recovered quicker from the disruption caused by weaning stress than piglets fed the control diet.

A shift in response of a range of metabolites, such as cholic acid, choline and taurine levels, was found in piglets fed the blend. This indicates a shift in bile metabolism and potential increase in bile production and secretion. Higher levels of cholic acid may improve nutrient digestion and support the growth of beneficial bacteria. Lower levels of circulating creatinine suggest higher muscle metabolism for the blend-supplemented piglets. Control pigs demonstrated dramatically higher levels of creatinine, indicating decreased metabolic activity and a negative energy balance.

Improving ADG and feed efficiency

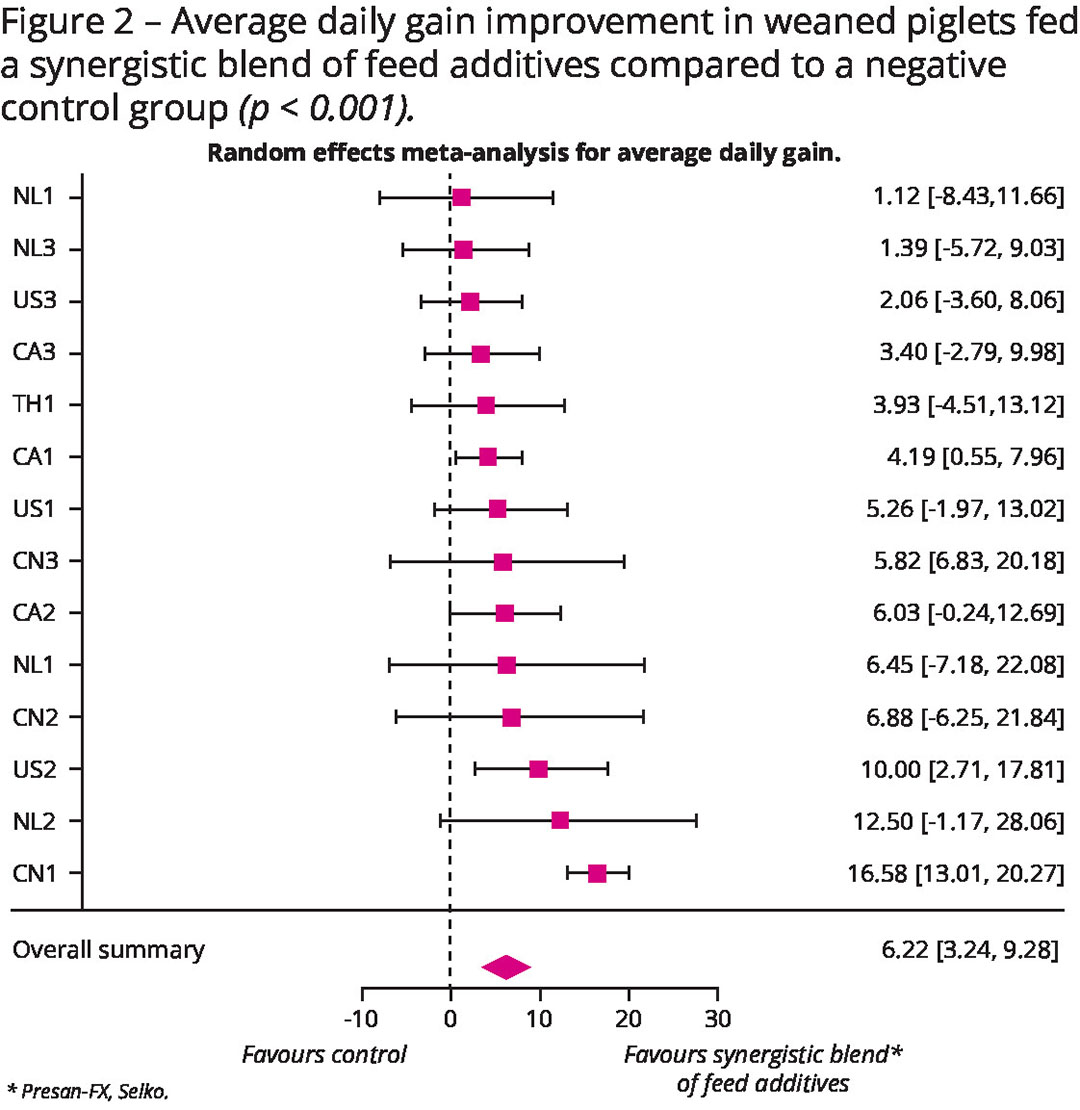

A meta-analysis was performed from 14 scientific trials conducted in 8 research institutes globally and including 2,668 animals. The Presan-FX inclusion rate in the piglet diets was 2.0 or 3.0 kg/t and piglets were either not challenged or were exposed to a hygiene challenge. Studies lasted from 28 to 42 days. Results show, on average, a consistent improvement of 6.2% in average daily gain and 3.2% in feed efficiency (Figure 2). This efficiency improvement adds € 0.75 of value per piglet.

The bottom line

Studies suggest economic reasons for including the blend in the piglet diet, as it improves gut function by supporting the establishment and growth of helpful bacteria and maintaining tight junctions in the intestinal tract, leading to improved nutrient digestion and daily gain. The feed additive also reduces competition for nutrients and improves feed efficiency, which may add up to € 0.75 of value per piglet. Adding a blended feed additive that includes MCFA, organic acids with high pKa value and phenolic compounds to piglet diets has been demonstrated to benefit production and the bottom line.