Gut integrity in piglets – The first line of defense

A healthy functioning gut barrier and an intact mucus layer is crucial to combat potential infections post-weaning.

The gut barrier is the first line of host defence

The gut barrier is one part of the innate immune system, which comprises the first line host defence mechanisms against pathogen exposure. The main component of this barrier is the intestinal epithelium lining which forms the luminal surface to the external environment of both the small and large intestines. The luminal side of the intestinal epithelium is covered by the mucus layer which serves several purposes. It forms a lubricating selective barrier which traps pathogens and unwanted substances and washes them off as the mucus gets replenished. A key component of the mucus layer are the mucins, which are proteins covered in chains of sugar and which stick together to give the mucus its gel-like structure. The mucins are produced primarily by Goblet cells – one of the specialised cell types that make up the intestinal epithelial lining.

The immune system of the newborn piglet is underdeveloped due to missing antibody supply from the placenta, and acquisition of passive immunity through colostrum and milk is therefore crucial for survival. Colostral and maternal antibodies provide the first source of immune protection. However, the maternal supply of antibodies under commercial pig production is withdrawn at weaning, leaving the newly weaned pig in a vulnerable state as the active immune system is not yet developed. A fully functioning innate immunity including having a healthy functioning gut barrier and an intact mucus layer is therefore crucial if the pig is to combat potential infections post-weaning.

In vitro studies demonstrate the potential of SolPreme strains

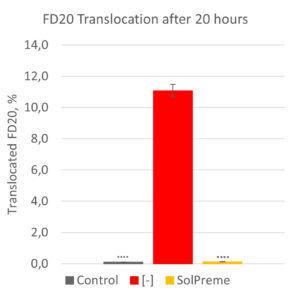

Using the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) assay, a healthy and a compromised gut barrier can be mimicked. In this assay, the amount of fluorescein isothiocyanate tagged sugar molecules (FITC-dextrans) that translocate from the apical side across the cell monolayers can be measured. The greater the amount of translocated FITC-dextrans, the more “leaky” is the cell monolayer. In Figure 1, this assay has been used to demonstrate the potential for the probiotic product SolPreme to support gut barrier integrity. The intestinal epithelial cell monolayers were incubated with or without SolPreme and then exposed or not to the reactive oxygen species (ROS) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a model for oxidative stress. ROS are natural by-products of cellular metabolism. However, excessive ROS can lead to oxidative stress which can cause damage to cells. What we see is that H2O2 increases FITC-dextran-20kDa (FD20) translocation. But when we co-administer SolPreme to the H2O2-exposed cells, we see a prevention of FD20 translocation (Source: Internal).

Figure 1- Protective effect of SolPreme on limiting the gut barrier damage caused by 5mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). TEER measurements were carried out for 19h, after which the amount of FITC-dextran-20kDa (FD20) translocated across the epithelial cell monolayer was quantified.

**** = P<0.0001.

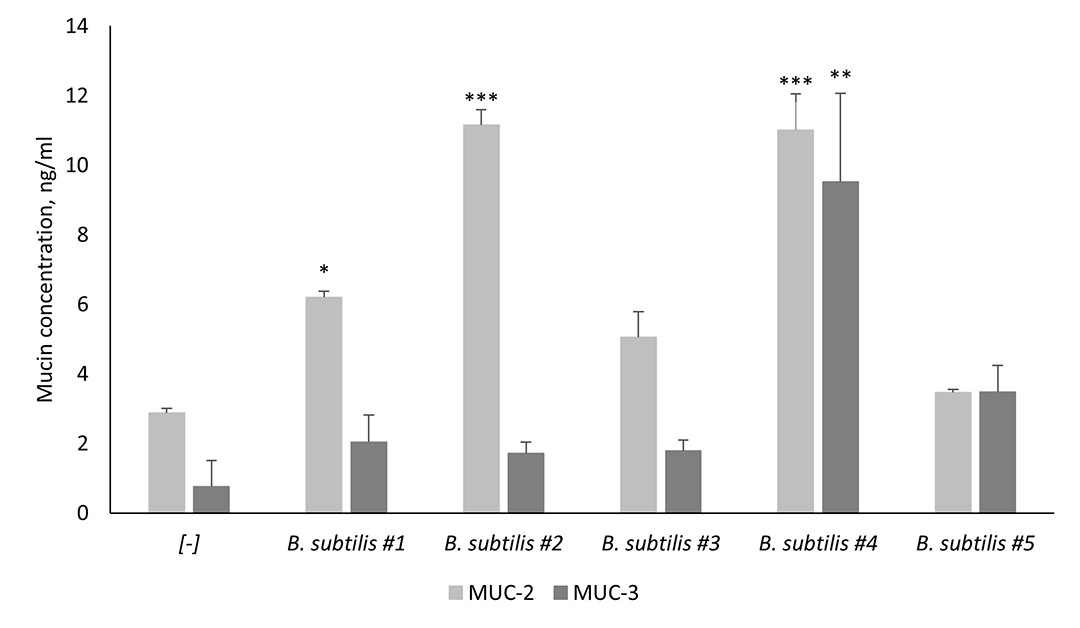

As mentioned previously, mucins are a key component of the mucus layer, with the MUC-2 and MUC-3 genes being recognised as the most important ones. MUC-2 is the most abundant secreted mucin in the intestine, whereas MUC-3 is found on the surface of enterocytes and goblet cells (Peterson & Artis, 2014). Probiotics can induce the production of goblet-cell-derived mucins, however, not all probiotic strains possess the capacity of inducing the secretion of mucins. According to Santano et al. (2020), strains matter when it comes to the ability of stimulating the secretion of MUC-2 and MUC-3 proteins (Figure 2). B. subtilis #4 which is one of the two strains in SolPreme is superior when compared to the other B. subtilis strains at stimulating the secretion of both mucins tested.

Figure 2 – Stimulation of mucin secretion (MUC-2) and surface expression (MUC-3) from Goblet-like intestinal epithelial cells co-cultured with different B. subtilis strains. B. subtilis #4 is one of the two strains in the probiotic product SolPreme.

*P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; ****P≤0.0001.

In vivo studies confirm the epithelial protection of SolPreme strains

Pathogenic E. coli has been shown to compromise the gut barrier, however, in an in vivo study Kim et al. (2019) demonstrated that application of the SolPreme strain B. subtilis to E. coli F18 challenged nursery pigs alleviated increased intestinal permeability.

Stimulation of mucin secretion has been demonstrated in a recent study investigating the effect of administrating SolPreme to sows and their piglets on the development of the immune system (Konieczka et al. 2022). SolPreme application increased the thickness of ileal mucosa due to longer villi in piglets at weaning (P<0.05), enhancing the first line defense of those piglets prior to the event of weaning. In the same study, Konieczka et al. (2022) demonstrated that administration of SolPreme to sows and piglets increased the Peyer’s patch size of piglets at weaning by 39% compared with control piglets (P<0.05).

Feeding SolPreme to sows and piglets has a direct stimulatory effect on epithelium and the mucosal immune system. With the benefit of having a more developed mucosal immune system, the pig can utilise its energy on growth, improving performance.

References are available upon request. Learn more about gut integrity in a probiotic perspective here.