Farm visit: Along came ASF – and the future evaporates

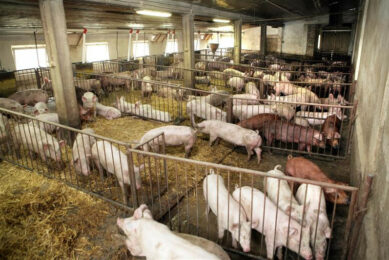

Thomas Paul is a pig producer in Hesse state, Germany. His future in the business suddenly became very uncertain when his farm had to be emptied and properly cleaned due to an infection of African Swine Fever (ASF) that visited his farm. A restart is not to be expected any time soon.

Within a period of only 6 weeks, the existence of Thomas Paul’s pig farm has become completely uncertain. In mid June 2024, the first case of African Swine Fever (ASF) was reported within the wild boar population in the state of Hesse, where Paul has his farm. Initially, he was faced with a transport ban. When a gestating sow died on his farm in late July, the animal had to be tested for a virus. Seeing that his farm is in an ASF restriction zone, a routine test for the virus is mandatory for every dead pig. Its result, on Monday, July 29, yielded the worst possible outcome: the animal had died of ASF.

After that, things moved quickly. On 30 and 31 July and 1 August, all pigs on the premises were culled for preventive reasons. During that process, 2 more gestating sows died from ASF and a fourth sow also turned out to be infected. Prior to those moments, Paul had not noticed anything unusual about the infected sows. After all, in late July, there were a lot of flies and other insects. Sows then tend to have red spots due to rubbing, Paul explains.

Drastic event

The chain of events constituted a drastic event for Paul. In total 2,600 animals had to be culled, with a combined weight of 125 tonnes. Pigs under 20 kg were gassed. The heavier animals were electrocuted with specially designed tongs. Sows about to give birth were first given an injection, so that the unborn piglets would for sure be dead. Paul had to be at home to reset the operation in case of a power failure. Paul reflects, “That was not fun.”

A specialist from Germany’s reference lab, the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute (FLI), was present during the culling process. Blood was taken from every third pig. All results were negative. Apart from the 4 sows, no other pig had been infected.

Solid fencing

While Thomas Paul opens the 2 m tall access gate to the yard, he talks about what happened and the uncertainty he suddenly found himself in. The yard is spotlessly clean. The concrete pavement has been cleaned and disinfected twice. Paul says, “We can safely enter the yard. The pig houses have already been swept clean. We are only allowed in there once they have been cleaned and disinfected by a accredited company. At that moment, all the inventory will be moved aside and the slats have to be removed from the pit. I will never be able to fit those in these old pig houses.”

The sow facility dates from 1994. The piglets and the finishing pigs were located in a former cow shed, which was converted into a multi-storey barn in the 1980s with finishing pigs and piglets on the upper floor. The buildings are not brand new, but they still look neat. Feeding stations were used in the sow barn, says Paul.

A 2 m tall metal fence surrounds both pig barns and the spacious machine shed. Paul says, “This type of fencing can also be found around factory sites. I have three gates in the fence, each costing €7,000. There is a 0.5 m foundation under the ground. No wild boar or fox can get to the pig houses. The experts at FLI, therefore, suspect that a bird of prey left a piece of an infected wild boar carcass on the property. There is actually no other option.”

Regional sales

Paul normally produced 6,000 piglets, annually. He finished half of them himself and the other weaner pigs were then sent to six different buyers. The largest buyer would receive 104 piglets every 2 weeks. The weaner pigs for sale eventually would all end up on the regional meat market. The finisher producers would then arrange their sales via wholesalers and butchers. Paul explains that those pig farmers mainly feed by-products, including those from a dairy factory. In addition to a lot of barley, Paul normally fed a pelletised malt product from a brewery. That way, they managed to work very locally, for a low cost price and a little bit of extra margin. Until the chain collapsed in mid 2024, that is.

Paul’s pigs used to go to a local slaughterhouse called Simon Fleisch. Seeing that the pig numbers would only be small, he would normally take the pigs there himself. The trailer is in the tool shed. Paul: “I can load 20 pigs and 80 piglets. I simply didn’t have enough pigs to be able to fill an entire truck.”

Having culled the pigs, they yielded approximately 60% of the market price. The money came from an animal health fund, managed by the state government. The producer is not insured for consequential damages. Paul says, “The premium is €20,000 per year and then there are so many conditions that you often don’t get anything paid out.”

More important, however, is the payment of the costs for cleaning and disinfecting the pig houses. These are likely to end up on Paul’s plate, but he is not going to accept that. Paul says, “I am not to blame and it’s the government wanting the pig houses to be cleaned and disinfected. Then it makes sense that it would be them who’d pay. It was the authorities’ call.”

Disinfecting once more

Although the yard is spotlessly clean, Paul disinfects his footwear again to be on the safe side when leaving. That is also according to regulations. He then closes the gate and carefully locks it again. For the time being, having pigs is not an option. Depending on the zone in the restricted area, repopulation will only be possible at the earliest three months after cleaning and disinfection of the last farm. Paul reacts gloomily: “First let’s see who is going to pay for the cleaning and disinfection. I would prefer to keep pigs again. Arable farming and pigs are a nice combination in this region.”

In short: there is no date for a restart. There are a number of big bags with feed in the attic of the feed kitchen. Paul has a stock of ready-made compound feed and raw materials that do not have a very long shelf life. The latter concerns fishmeal. Paul also used to mill and mix feed himself. This also applies to the supply of raw materials. Now everything just stands there – without a purpose.