Non-antibiotic medication against swine dysentery

Bit by bit, the toolbox for controlling swine dysentery has become emptier in recent years. There is a global trend to limit the use of antibiotics as much as possible, and zinc oxide will also no longer be allowed at prophylactic levels in 2022. It is time for a new addition to the toolbox.

“Pigs of all ages are affected, although the peak incidence is in weaned pigs of six to 12 weeks of age,” writes Professor David Taylor in the comprehensive Health Tool at www.pigprogress.net, when discussing swine dysentery. He adds, “Vaccines are not available widely. Swine dysentery can be eradicated by medication or depopulation and restocking and kept out by isolation and use of clean breeding stock.”

For those swine farmers who do not fancy depopulation and restocking, the recent global trends in veterinary medicine have not been encouraging, as the use of antibiotics is being discouraged in many countries all over the world. The article on page 20, for instance, deals with the background of reduced antibiotics usage in the United States in recent years. Does that mean that all strategies are depleted?

Swine dysentery – the basics

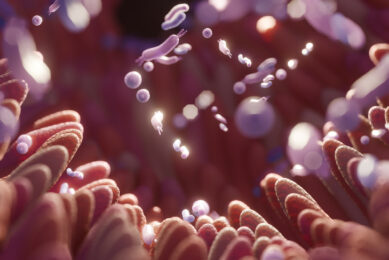

First things first – swine dysentery, what is it again? It is a severe bacterial diarrhoea condition caused by Brachyspira hyodysenteriae which is transferred orally, for example, by ingesting faeces or drinking infected water. The health problem usually only develops after weaning and the subsequent mixing of litters.

To quote Prof Taylor once more: “Diarrhoea develops and persists throughout the course of the disease. Blood, mucus and, later, pieces of necrotic material appear in the faeces which are yellowish in colour at first and later become brownish-red, liquid in consistency and foul-smelling. There is a rapid loss of bodily condition and pigs are thin with sunken eyes, hollow flanks and prominent ribs and backbones. Affected pigs show a variable reduction in appetite but all continue to drink.”

Zinc as intervention strategy

Apart from using antibiotics, there is one other intervention strategy known to control swine dysentery: zinc oxide. For a long time, zinc oxide has been added to feed at prophylactic levels of 2,500 ppm. Yet for environmental reasons, the addition of zinc oxide at these levels is being banned in the European Union for control of diarrhoea as from 2022.

That does not mean, however, that the component ‘zinc’ is completely out of the picture. It might still be useful when supplied in a totally different form, at lower dosages, as the Netherlands-based health and hygiene company Intracare discovered. The company has substantial experience with the production of chelated zinc products, for instance, to deal with infectious claw problems. In dairy cows a copper and zinc chelate has proven effective against digital dermatitis in dairy cattle, a bacterial problem caused by Treponema, classified as part of the phylum (biological level) Spirochaetes. Not surprisingly, the question arose as to whether this approach would also work for other bacteria in this phylum. B. hyodysenteriae was one of them.

As a consequence, the company introduced medication (Intra Dysovinol) based on a zinc chelate in a boat-shaped molecule, with a relatively low zinc concentration of 81mg/ml. The non-antibiotic medication can be added to drinking water.

Results, as described below, give reason for optimism. It is clear that it is related to the way the gram-negative bacteria B. hyodysenteriae normally colonises the intestine. Proteins on the bacteria’s outer membrane would normally release “haemolysin toxins” into the villi of gut epithelia. That would lead to villi degradation and subsequent bleeding, which is characteristic of swine dysentery.

In vivo studies demonstrated, however, that when applying the zinc chelate, B. hyodysenteriae was no longer attached to the intestinal cell wall and had been flushed out. The research team concluded that the zinc chelate must therefore be blocking the proper functioning of these outer membrane proteins (OMP). Hence, the zinc chelate is introduced as “OMP blocker.”

Effects on swine farms

In the Netherlands, a team of researchers with GD Animal Health and Intracare carried out a trial to test the effects of that approach on clinical appearance, faecal quality and excretion of the bacteria. In 2017, the team investigated the situation on two commercial pig farms in the Netherlands experiencing clinical swine dysentery in grow-finisher pigs.

- Farm A was a multiplier farm consisting of 670 sows;

- Farm B was a grow-finish farm consisting of 2,180 grow-finish pigs.

The research team chose in total 64 pigs in eight pens per farm for close, individual follow-up. As six pigs did not excrete B. hyodysenteriae at the start of the trial, the scientists used 58 study pigs to assess the efficacy of the medication in the treatment of clinical signs. Of the 58 enrolled pigs, 30 received placebo (four pens per farm) and 28 received zinc chelate treatment (four pens per farm).

Faecal quality scores

At the start of the trial, the faecal quality scores of the individually monitored pigs were quite comparable between all pigs. Yet that was soon to change. The researchers wrote, “The results of this study clearly demonstrated that low concentrations of the zinc chelate significantly reduced clinical signs and shedding of B. hyodysenteriae.” Treatment with the OMP blocker, they added, resulted in a significant improvement in faecal quality (see Figure 1), and after six days it was not possible to detect any B. hyodysenteriae in faeces by PCR.

They went on to describe that in the placebo-treated group, 17% eventually collapsed and 48% of the remaining pigs required additional therapeutic treatment. The scientists also observed no relapse by clinical appearance and faecal quality on day 14 of the trial.

Within 6 days

All in all, the researchers concluded, treatment with the zinc chelate had ceased the shedding of B. hyodysenteriae within 6 days and ceases the clinical signs of B. hyodysenteriae in naturally infected pigs for at least an additional eight days after cessation of oral therapy. That resulted in a higher growth rate of treated pigs and improved general health. In addition, the team did not observe mortality and no additional treatment was needed.

So, while the toolbox is getting emptier with antibiotics and zinc oxide gradually disappearing, the good news is that when one door closes, another one opens.

The research discussed in this article was published in the peer-reviewed journal Veterinary Record in 2019. References available on request.